Media plan directs reporters away from sources

May 5, 2008

A new proposal designed to improve the media’s relationship with the college district is already causing confusion among top officials and delaying journalists’ access to information.

The proposal calls for district employees to direct media inquiries to a college president, public information officer or designated spokesperson if asked a question that requires an “official statement” on behalf of the district, said Timothy Leong, the district’s new director of communications and community relations.

Leong said he drafted the proposal, which he calls a “media relations plan,” in order to improve the district’s relationship with the media.

Leong said his plan has three main points: 1) to provide a timely response to media inquiries; 2) to coordinate within the district to give “official messages” on behalf of the district or each college; and 3) to “minimize employee impact” when responding to media inquiries.

Leong said his plan is not limited to media inquiries during a time of crisis.

Although he said he has not yet put his plan in writing, district police services at DVC began acting on it last month..

An Inquirer reporter checking on whether police services was understaffed at DVC was told he could not speak to district police chief Charles Gibson without going through DVC public information officer Chrissanne Knox.

An Inquirer editor seeking an interview with Gibson was referred to Barbara Cella, the director of marketing and media design at Los Medanos College.

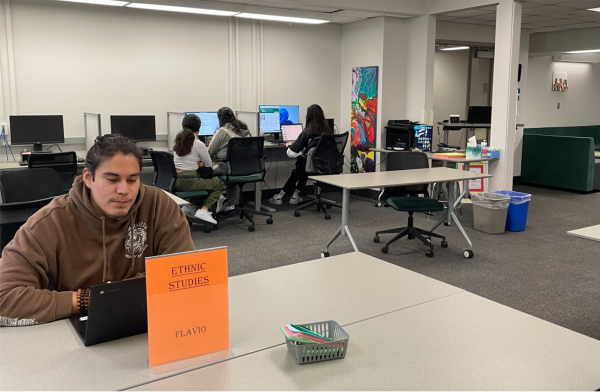

And a beginning newswriting student working on a story about campus safety at night was told by Lt. Tom Sharp she had to get the information from Knox, who would get the information from him.

The student submitted her questions to Knox and did an interview with Sharp a few days later in the presence of Knox.

When asked by an Inquirer editor about Leong’s plan, district Chancellor Benjamin said it should only govern the flow of information during a crisis.

“If you’re doing a routine story, it would be cumbersome to have to go through a PIO,” Benjamin said during a phone interview. “It’s more in my mind for emergency events.”

But Leong said he had cleared up the misunderstanding with Benjamin this week and she had no objection to his plan covering non-crisis situations.

DVC made headlines nationwide after Contra Costa Times reporter Matt Krupnick broke the story in January 2007 that DVC students were suspected of selling grades out of the admissions office over a seven-year period.

District and college officials were criticized in several Contra Costa Times editorials for keeping the scandal secret after discovering it 18 months earlier.

But Leong, Benjamin, Knox, and DVC President Judy Walters denied any connection between the proposal and the criticism DVC and the district received for what was considered a lackluster PR response to the cash-for-grades scandal.

“The intent [of the plan] is to have a process that is clear and simple for information to flow,” Walters said. “And that those people who need to be in the communications loop are in the communications loop.”

Leong said his plan “doesn’t need to be a governing board issue,” because it is not an official district policy or procedure.

Knox, DVC’s public information officer, said the plan was never an order and that no one was told they had to comply. The district has no plans to punish anyone who fails to comply the plan, she added.

“It is unfortunate [the plan] has been communicated as a policy or directive,” Knox said. “[We are] not in the business of trying to withhold information.”

But she said college officials contacted by the media should contact her before or after doing an interview to “help the college convey messages to the community.”