Against the Grain – How the Bay Area is changing the meat industry

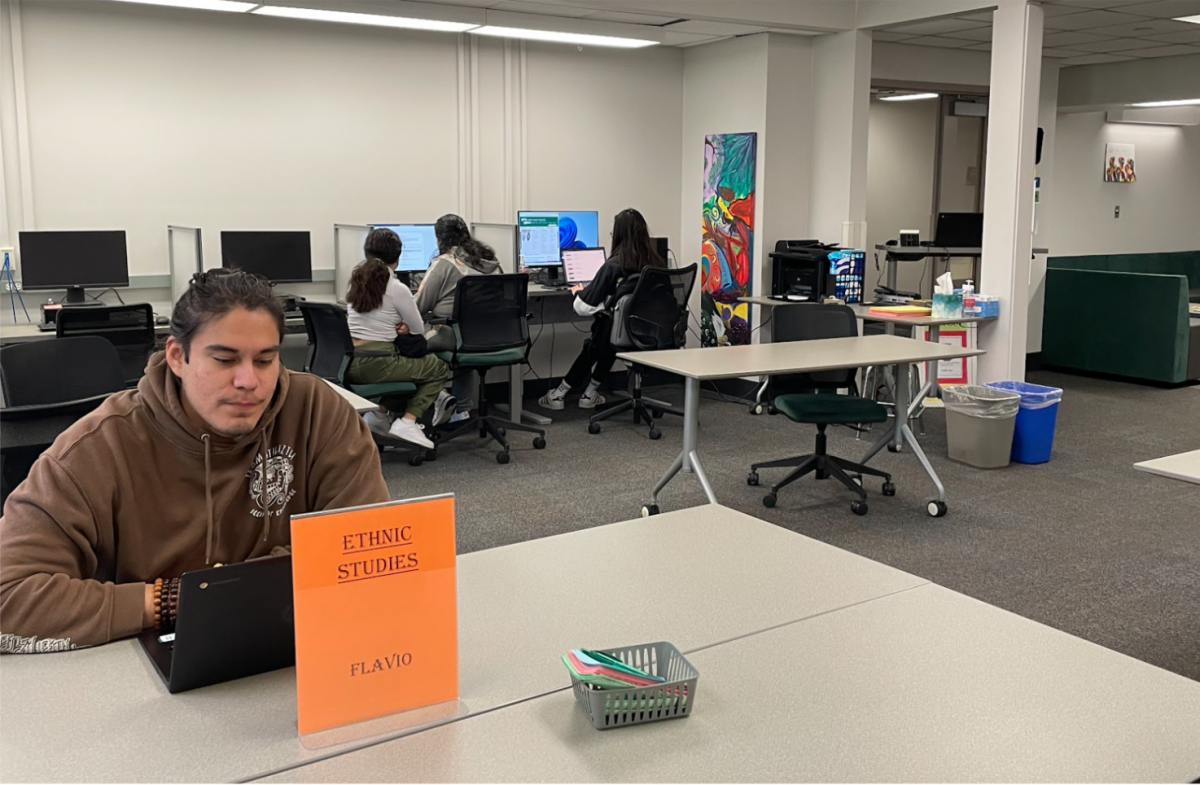

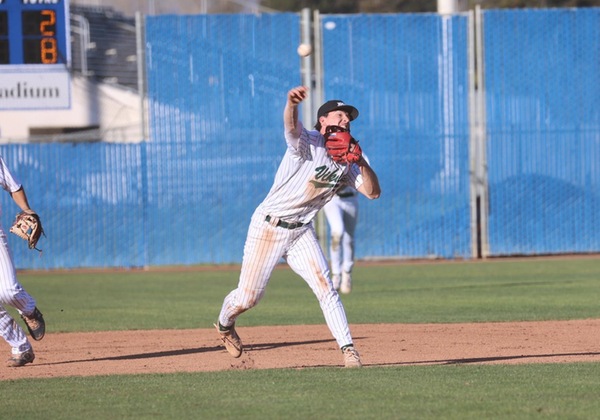

Cattle that live their lives on pasture provide more nutritionally dense meat than their factory farmed counterparts. Photographed by Tyler Skolnick in Point Reyes, on April 28th, 2018.

May 10, 2018

Bay Area consumers have been pulled into the center of a debate about status quo procedures and behavior the meat industry, the onus is now on conscious consumers to drive the future of how we treat ourselves and our animal counterparts in this process.

The veil has gradually been pulled back on the behaviors of the large scale establishments in the meat industry. What people find behind it has, for many, become too disconcerting to ignore.

Those who have consumed meat for their entire lives are having their eyes opened to the truth about what the industry has become. As with many of the great social movements of our past, change often starts with engaged students.

Adriana Alvarez, a Bay Area student and activist, “I dove into the information while doing a school project about factory farming. I found out about the conditions animals are kept in, how the animals were slaughtered, and the hormones and antibiotics they inject the meat with…”

But what did she discover about factory farms that would ultimately put this issue in the center of her life as a community member and activist?

Factory farming is characterized by the industrialization of meat production, large numbers of the same animal confined into small spaces. The farms chase higher output and increased profits, while forfeiting ethical practices and product quality, according to critics of the industry.

The practice developed to meet rising consumer demands. It represents a step in a radically different direction from the small to medium sized farms that were the norm for much of recent human history.

The problems that many find with the status quo in the industry can be ultimately placed into two categories. Ethics and nutrition.

Along the ethical front, the Berkeley Animal Rights Center takes a hardline stance against factory farming and animal commodification as a whole. They provide one answer to those who not only find an ethical problem with factory farming, but with our current human relationship with animals.

Nathan Fisher, an activist from the Berkeley Animal Rights Center, describes that their goal is not limited to decreasing suffering of animals. These activists hope that animals cease to be seen as items that can be bought, sold, and defined by human standards.

On the topic of factory farming, Fisher conceded that factory farming is the bigger enemy at the moment in their cause.

Yet the overall goal of the activists is to end “speciesism.” Fisher defined this term as, “one species thinking they are better than another species simply because they are said species… that way of thinking doesn’t have any moral justification. In the same way as racism, sexism, or any other -ism.”

To those hoping to address a moral qualm surrounding their participation in the factory farming system may see abstaining from animal consumption altogether as a viable option on the table.

Yet for those that wish to continue to consume meat products, factory farming presents a myriad of nutritional problems.

During Alvarez’s research into the industry, she began to develop the belief that the practices in this industry were unhealthy for both the animals and the people who ate them.

Factory-raised cattle are housed in intensely close quarters, and owners utilize antibiotics to keep their animals healthy. In his presentation at DVC, Dan Williams from the Ethical Choices Program outlined this issue in his presentation at DVC.

“The conditions that these animals are raised in are perfect for the rapid spread of disease, a diseased and dead chicken or cow for me as the farmer is not going to be helpful or valuable so I need to prevent that from happening, and I do that by feeding antibiotics to the animals everyday…”

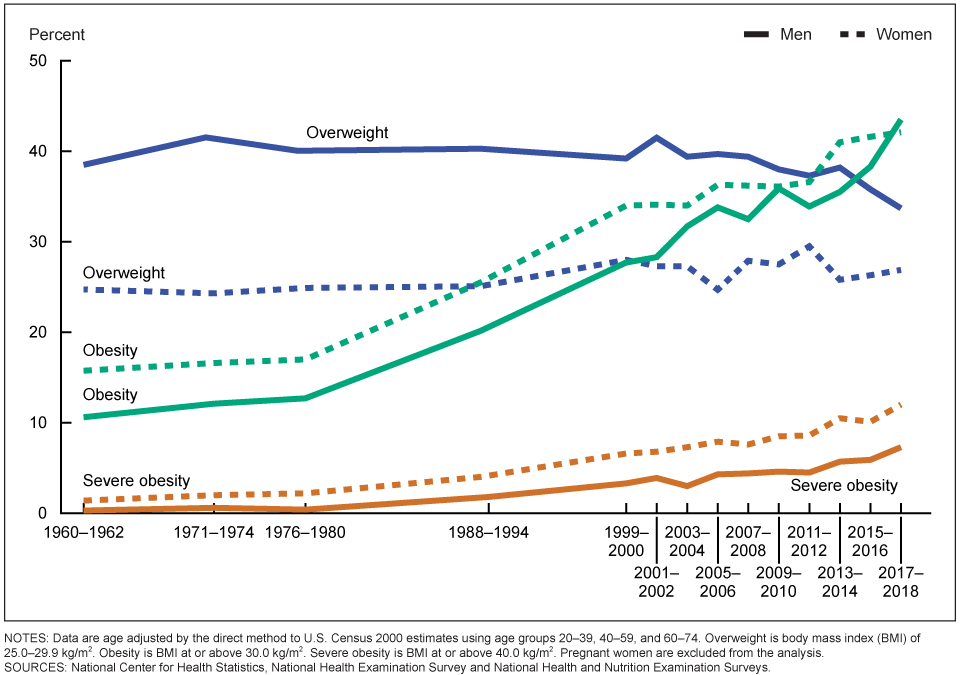

According to the National Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production (NCIFAP), around 80% of the antibiotics sold in 2011 were for the purpose of meat and poultry production in America.

Williams alleges that these methods could potentially manifest “superbugs” that can spread to human populations, citing examples like the bird flu and swine flu.

Ethical treatment of animals has been proven to provide more nutritious meats. Happy, healthy animals leads to quality healthful meats.

According to Kristin Osowski, a passionate nutrition educator and DVC professor, recommends that grass-fed, pasture-raised animals are the healthiest way to consume animal protein. “When you select animal products, choose grass-fed. Buy organic,” Osowski encourages, “do the best you can.”

The nutritional content of pasture-raised, grass-fed animals are measurably different than factory produced meats. Consuming grass, shrubs, and other herbs provides animals with a different nutrient profile than that of their corn-fed factory counterparts.

Raising animals on pasture will provide better quality products for consumers to eat. Grass-fed meats have higher levels of essential vitamins and minerals, these don’t become a part of the meat with a grain or corn based diet. They are also naturally leaner and happier animals.

This trend also applies to chickens and eggs. Chickens that are pasture-raised have visible differences in the eggs they produce. Yolks that have origins in healthy hens have stronger shells, and deep orange yolks. A study published by Cambridge University Press found that hearty healthy omega-3s, as well as vitamins A and E increased radically in pastured hens.

Osowski has committed to finding grass-fed beef from local Bay Area farmers, “I buy my meats at the farmer’s market and also from a local farmer…” She and friend purchase half a cow, sharing the meat and bones to make the most of the purchase.

Companies in the Bay Area have caught onto the “quality over quantity” trend and have grown businesses around providing better quality meats and animal products. The hills of Marin County are the homes to pasture-raised cattle, raised by companies that want to turn back the clock and continue to sustainably raise these cattle.

Marin Sun Farms is a vertically integrated company that handles their animals from the farm, all the way to the point of sale in butcher shops. Their model, along with companies like theirs, represent another choice laid in front of the conscious consumer who is trying to confront both the ethical and nutritional front.

Former COO Daniel Kramer, who helped to build Marin Sun Farms’ operation, was not happy with the conventional ways of raising cattle. “Our alternative was to support local ranchers here in the food shed, and be able to give them a way, a market, here in the Bay Area…”

In a 2013 presentation at Stanford University, Kramer outlined why raising cows 100% grass-fed is so important. “This is the way cows are designed to work… Cows and other ruminates are able to take grass and magically transform it into delicious things like ribeye steaks.” He pointed out that this process had been developed over tens of thousands of years of animal domestication, yet the economic model to support this has been lost.

The goal was to reconnect that pasture-raised, grass-fed cow back to plates in the Bay Area.

For consumers like Alvarez, who express genuine concern about where their food comes from, transparency is important. The facilities that Marin Sun Farms uses are Animal Welfare Approved, a certification that could carry a lot of weight to those who consider ethical production to be at the heart of their food choices.

Alvarez believes that entities that operate large conventional factory farms cannot be trusted to act ethically, “These companies try to mask (production protocols) from you, they try to cover it and hide it.”

In many states where animal agriculture corporations have political swing, this is largely true. Dan Williams, who represents the Ethical Choices Program, discussed how companies mask their procedures when handling animals and meat.

Many states have passed legislation, known as “ag-gag” laws, that legally punish those that wish to broadcast activity on large farms without the owner’s consent. According to Williams, ag-gag laws are passed and lobbied for to prevent the exposure of unethical practices that would turn consumers away from their products.

Idaho is among 11 states who have passed ag-gag laws, Section 18-7042, potentially punishes anybody who, “enters an agricultural production facility that is not open to the public and, without the facility owner’s express consent or pursuant to judicial process or statutory authorization, makes audio or video recordings of the conduct of an agricultural production facility’s operations.”

Idaho previously had this ag-gag law written into state legislation, until a district court judge ruled much of it as unconstitutional. The judge cited first amendment protections of freedom of speech and freedom of the press in his decision.

The true practices of the large-scale meat industry are rarely met favorably by those who encounter it. These issues have caught the attention of Silicon Valley venture capitalists and innovators. Emerging biotechnology companies have their sights set on a solution that could flip the debate on its head.

These companies are where food and agriculture meet Bay Area technology. Companies like Memphis Meats, are focusing on bringing lab-grown meat to market. Finless Foods has plans to bring seafood to our plates without the fish. And Clara Foods is in the process of developing egg whites, with no egg, and no chicken.

All of these companies have set up shop in the Bay Area, but what are they promising to develop?

Take Memphis Meats, they have received much of the media attention in the past year. Attracting notable investors like Bill Gates and Richard Branson, the company has created interest around their new product.

Without getting bogged down with the biology and the science, what these companies promise is meat that is molecularly identical to the muscle cells that make up the meat you can buy at the supermarket today. The lab setting omits the biological and agricultural process of raising an animal for slaughter.

Uma Valeti, CEO and founder of Memphis Meats, asserts that the product that they are working on is better for the environment, as well as the human and non-human animals involved.

Valeti cites many of the concerns that Alvarez and consumers like her have expressed. The rapid changes and rate of production that comes from factory farming cannot be sustained. Antibiotics, hormones and other contaminants make the Memphis Meat’s product, “more natural than what we’re eating now… There is nothing natural about the meat we are eating now.”

On the ethical and nutritional fronts that have been addressed, the concept of lab-grown meat is a massive leap forward on the ethics side. If one’s benchmark for ethics is reducing suffering, “clean meat” would appear to be that solution. While the conversation about nutrition of is yet to be had.

Clean meat sounds like an intriguing solution for many, yet there are no products on the market from these companies. The impact of these food technologies remains to be seen.

Uma Valeti acknowledges that the fate of his company and others like his are in the hands of educated, conscious consumers. The demand for his product will make it affordable, and then begin to change the way we look at animal protein.

Eventually, many individuals will find themselves in front of a similar decision to what Alvarez had to face. She, and the options in front of her, are the same that anybody in the Bay Area is fortunate enough to choose from.

The only way to change the future of the meat industry is for individuals to continue to make informed choices with their dollars and diets. Each purchase and each bite will shape this changing landscape.