How “Pandemics Amplify Historical Inequities”: Prof. Jose Aguilar-Hernandez On Socioeconomic Disparities During COVID-19

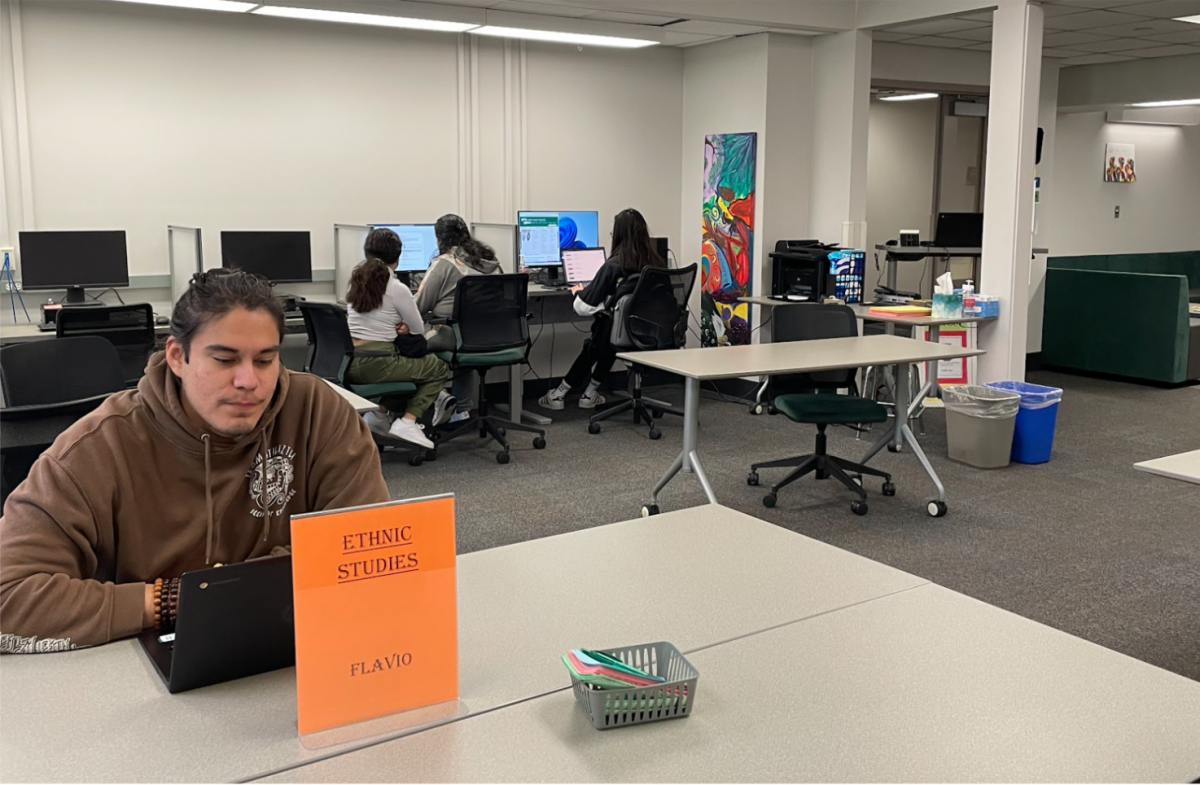

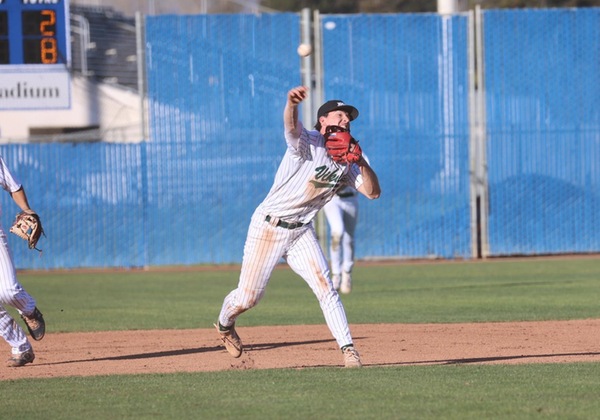

The Zoom event was attended by more than 100 students and faculty. (Photo courtesy of Diablo Valley College)

May 13, 2020

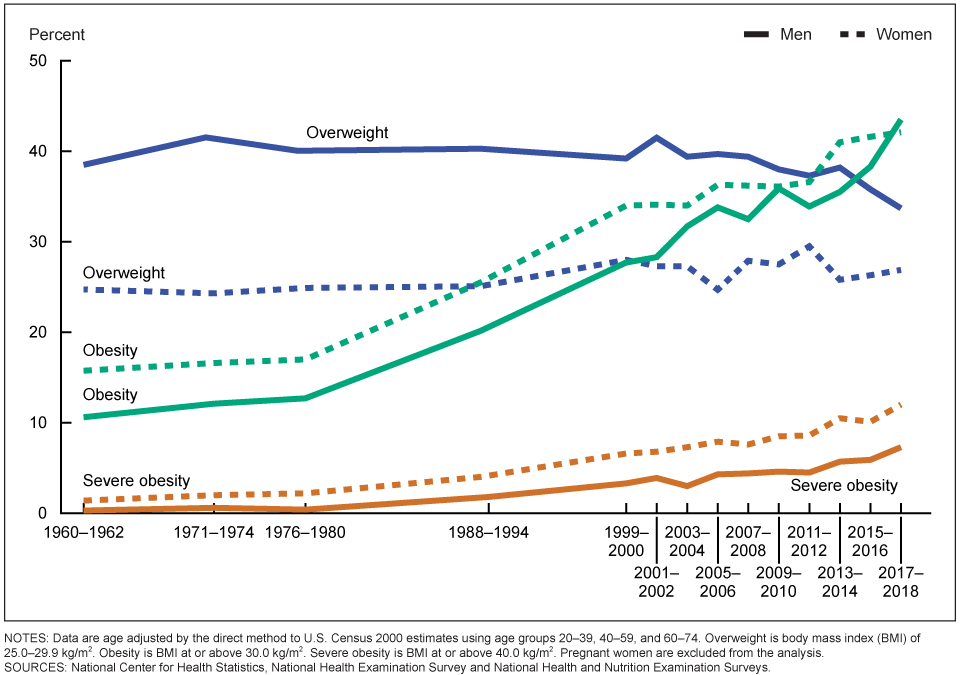

For millions of Americans, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused untold health and economic hardships. But perhaps the toughest blow, according to ethnic and women’s studies professor Jose Aguilar-Hernandez, has fallen on members of minority groups whose historical socioeconomic disadvantage is being amplified by the crisis.

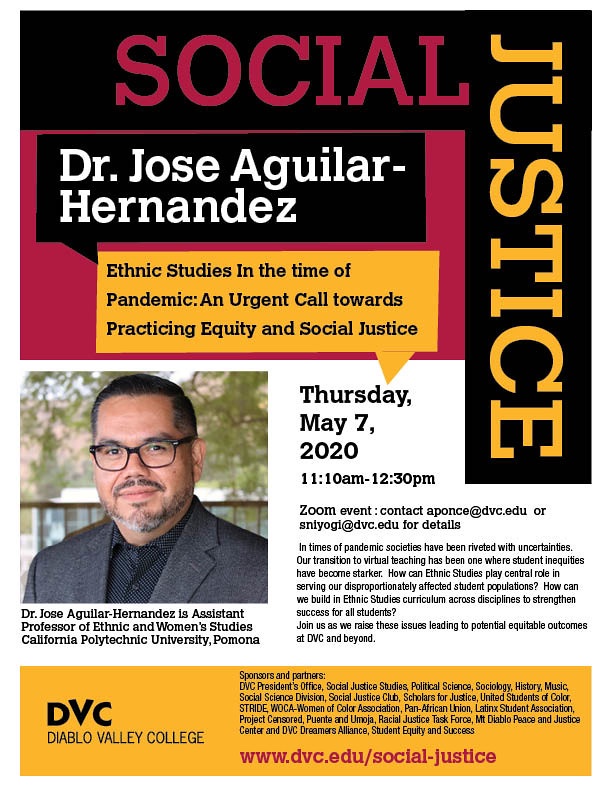

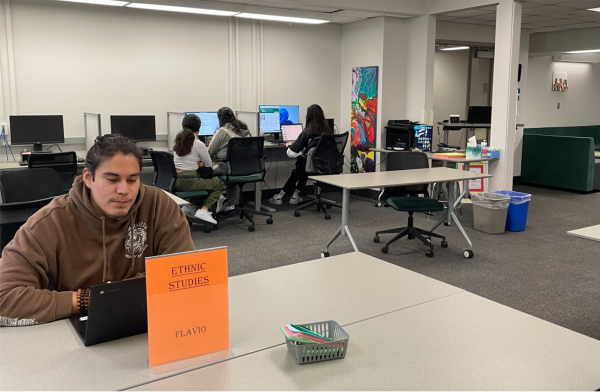

Prof. Aguilar-Hernandez, who teaches in the College of Education and Integrative Studies at Cal Poly Pomona, was the guest lecturer at Diablo Valley College’s social justice speaker series last week. In his speech, he highlighted the pandemic’s role in magnifying the country’s social inequities. He also emphasized the urgent need for ethnic studies programs to reveal and solve these heightened inequities.

The event, which took place in a May 7 Zoom session hosted by the college’s social justice program, was the last speaker series event of the semester and was attended by more than 100 students and faculty.

“Pandemics magnify historical inequities,” Aguilar-Hernandez said, listing police brutality, racial stereotypes, health disparities, pay gaps and anti-immigration policies as examples of inequities that have been amplified during the coronavirus crisis.

To back his claim, he used the example of a viral tweet comparing two photographs that showed the difference in the New York Police Department’s response to social distancing orders in white versus black communities. In one photograph, a police officer dressed in civilian clothing is seen wrestling a black man to the ground for violating social distancing orders and not wearing a mask. In the other photograph, police officers are seen handing out face masks to young white people in a Manhattan neighborhood who were also in violation of social distancing orders.

“Here we are in the middle of a pandemic and instead of the New York Police Department also handing out face masks in black communities, they are using police brutality to enforce social distancing (orders),” Aguilar-Hernandez said.

Other instances of heightened inequity can be found in recent reports by The New York Times documenting conditions in the Navajo nation, where communities lack access to running water and have suffered a disproportionate amount of coronavirus cases. The situation is alarming, he added, considering the precautionary measures provided by both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advising people to regularly wash their hands.

“How do you wash your hands when you don’t have access to running water?” Aguilar-Hernandez asked. “This isn’t that Native Americans don’t like running water or are somehow backwards because they don’t have running water. This is historical! Native Americans have been denied access to running water under the U.S. empire.”

He cited other reports like one by the Washington Post showing that members of the Latinx community are twice as likely as whites to have lost jobs during the pandemic. This blunt statistic, Aguilar-Hernandez said, “says a lot about how the majority of Latinx folks are employed in low wage jobs.”

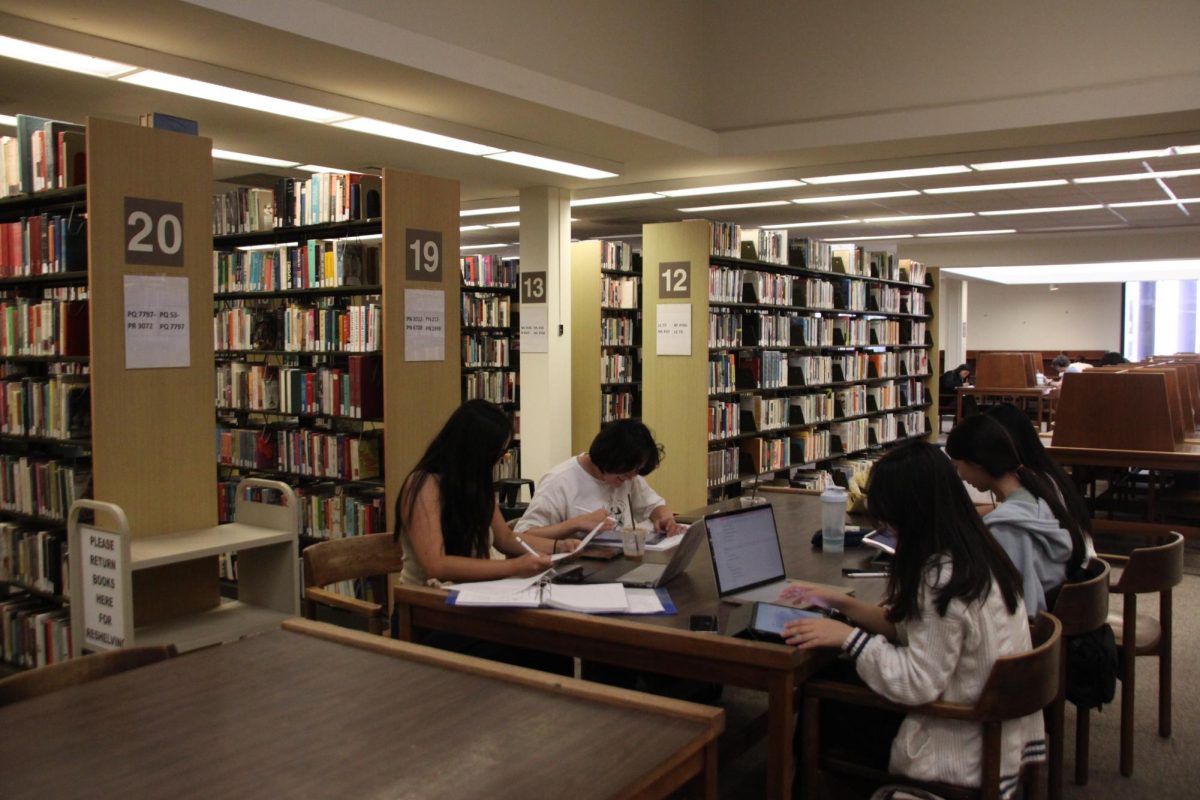

He further warned that the inequities magnified by the virus will likely extend into the educational system and affect, as they have done historically, minority programs such as ethnic studies.

“During pandemics or any type of economic crisis, ethnic studies (programs) experience budget cuts, downsizing, and elimination,” he said, adding that such an outcome now will be especially devastating given the important role ethnic studies programs play in unveiling and addressing disparities.

“One of the solutions to historical inequities is ethnic studies,” Aguilar-Hernandez said, explaining that the field’s inclusive pedagogy disrupts dominant narratives. He called on students to demand protection for their ethnic studies programs, stating “it has historically taken students to make demands to create change.”

While ethnic studies programs seek to transform institutions and policies, they most importantly aim to liberate, he added, and liberation “means the end of inequity.”