Quakin’ campus

Black and white photo of an aerial view of the burned area, Market Street on left, from Ferry Tower, San Francisco, 1906. ()

November 9, 2011

On May 11 of this year, Italians fled Rome on a massive scale. A seismologist’s century-old prophecy foretelling the approach of a momentous earthquake inspired a massive reaction: businesses reported requests from one in five people to have time off work as thousands of people fled the city in favor of safer surroundings.

Six months later, the recent rash of small earthquakes centered in Berkeley has led to a similar reaction among Northern Californians.

Berkeley has been shaken by eight quakes in the past month. On October 20, a 4.0 quake hit UC Berkeley, followed by a 2.8 and 2.5.

This time, rather than procure concern from what had been predicted 100 years in the past, the public is accumulating apprehension thanks in part to modern technology.

Not only have chain letters stemming from a respected local university official circulated warnings of “The Big One,” but entire websites have been dedicated to false prophecies of looming earthquakes.

According to an article from the New York Times, Dr. Genie Stowers of San Francisco State University wrote that there would be “a 30 percent chance of an earthquake above a 6.0 magnitude on the Hayward fault in the next two to three weeks” in an email she sent to colleagues and friends Halloween weekend.

The Hayward fault runs right underneath the UC Berkeley campus.

“No one can predict earthquakes with any sort of reliability. It is not unusual to see “swarms” of small earthquakes in a relatively small area,” said DVC Geology professor Jean Hetherington.

“It is likely that the recent events represent one of these swarms.”

Quakeprediction.com is one site that has capitalized on the concerns of the locals, predicting that San Diego, San Francisco and Los Angeles are all currently in a state of “very high risk.”

Although the owner of the site, Luke Thomas, claims that a magnitude 6.0 earthquake will occur “likely soon in the San Francisco Bay area…near Mill Valley, San Rafael, Berkeley, San Carlos, San Jose…” it is, in fact, impossible to predict earthquake date, time, magnitude and epicenter.

Magnitude classes span from “micro” to “great.” If Thomas’ prediction came to fruition, the earthquake would be considered “strong.”

“Tomorrow? Could be,” said another DVC Geology professor, Jason Mayfield. “30 years from tomorrow? Could be. Earthquakes happen. They’re gonna keep happening. All we can do is a kind of forecasting – giving a mathematical probability.”

“It’s very regular to have clusters of earthquakes that then just go away. In some situations, four small earthquakes can lead up to the big one; but if you always said that, you’d be wrong most of the time.”

The U.S. Geological Survey, a federal source, has published a “Summary of Earthquake Possibilities in the SF Bay Region” that states, “…there is a 0.62 probability (i.e., a 62% probability) of a strong earthquake striking the greater San Francisco Bay Region over the next 30 years (2003–2032).”

But don’t expect any specificity.

“We don’t like to get in the business of predicting,” said Mayfield.

Prior earthquake predictions have been detrimental for the real estate and economy of unlucky towns and regions.

In addition to the outbreak of earthquake psychics, a cornucopia of myths has arisen as a result of the damage that has been done in previous California earthquakes. These include the concept that the golden state will one day “fall into the ocean.”

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the plates upon which the state sits “are moving horizontally past one another, so California is not going to fall into the ocean.”

However, the Survey says it is true that one day in the future, Los Angeles and San Francisco will “be adjacent to one another.”

This year, The American Society of Civil Engineers released a document which graded the San Francisco area’s infrastructure by category. Evaluation of the categories “resulted in an overall grade of “C”, with some of the categories being as desperately low as a “D+.”

“A lot of the Bay area has buildings from nearly 100 years ago, before a modern understanding of earthquakes,” said Mayfield. “In places like Oakland, it’s not mandatory to retrofit. There are places we need to go in and say, ‘Hey, we need to fix this.’ I personally think we ought to, but hey, I’m not in charge.”

According to the ASCE, in order to bring the overall grade up to “B” level, an additional annual funding of $2.83 billion would be needed.

The overall grade of the Bay Area’s transit system, BART, for this year is a “C.”

The poor grades might generate concern, given past tragedies like the destruction of the Bay Bridge and the failure of the Cypress Street Viaduct on I-880. It begs the questions, which of us are in the most danger and what can we do to stay safe?

Colleague to Hetherington and Mayfield, Dr. Dawnika Blatter, says that a person’s safety is directly decided by a number of circumstances.

“The danger from an earthquake depends on many factors, such as how close you are to the epicenter, what kind of building you are in, and what type of material the building is constructed on. Loose sediment and fill are the worst because they actually intensify the shaking,” said Blatter.

According to the Red Cross, the best thing to do during an earthquake is to “drop, cover, and hold under a table or desk.”

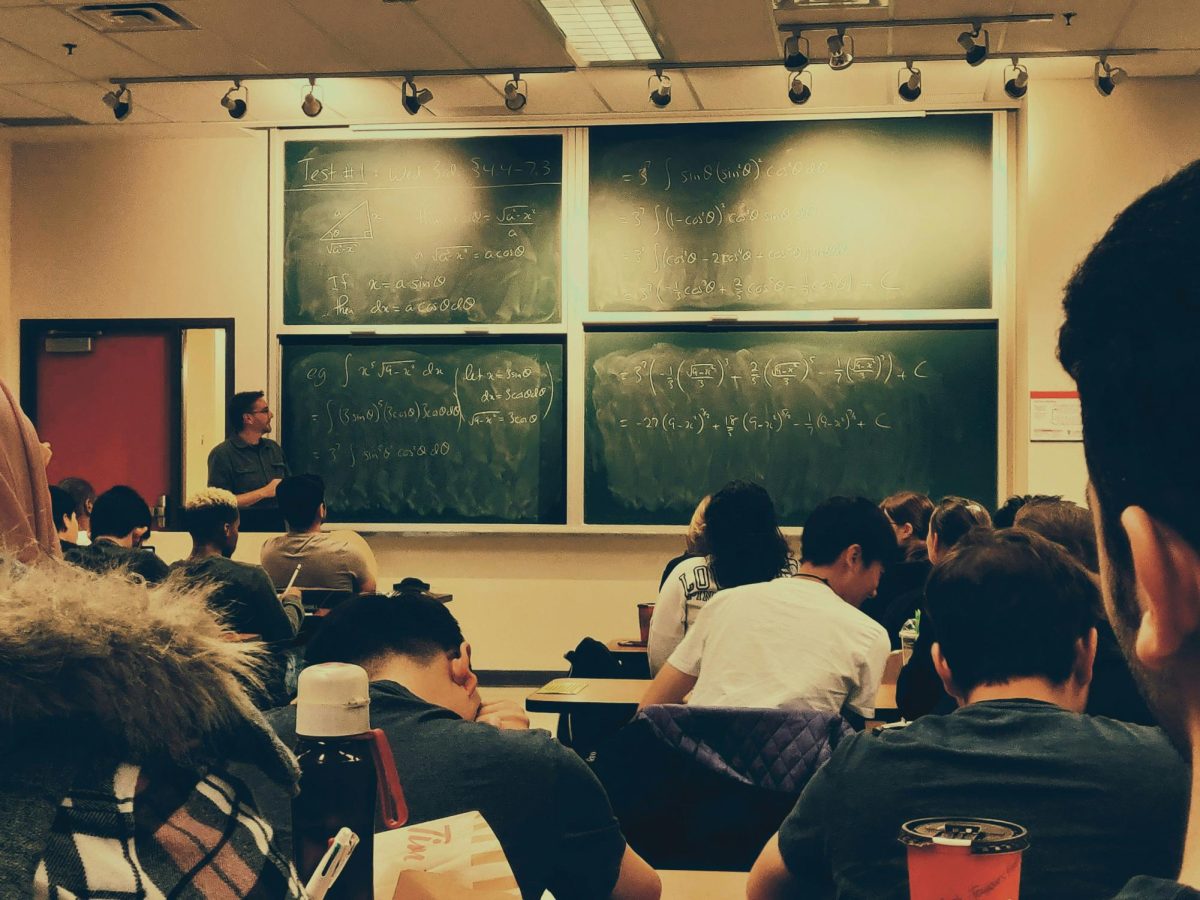

“It all depends on your location,” said Mayfield. “We used to tell students to get under their desks. If that desk isn’t strong enough and you tell them to get under the desk and the ceiling collapses, they’re caught under the desk. But if they’re sitting next to the desk, it might collapse a little but maybe they’re okay.”

“I don’t believe there’s a single best thing to do,” he added. “If I was in my classroom, I bet that steel doorway is where you’d find me.”