Pioneering a leading lady

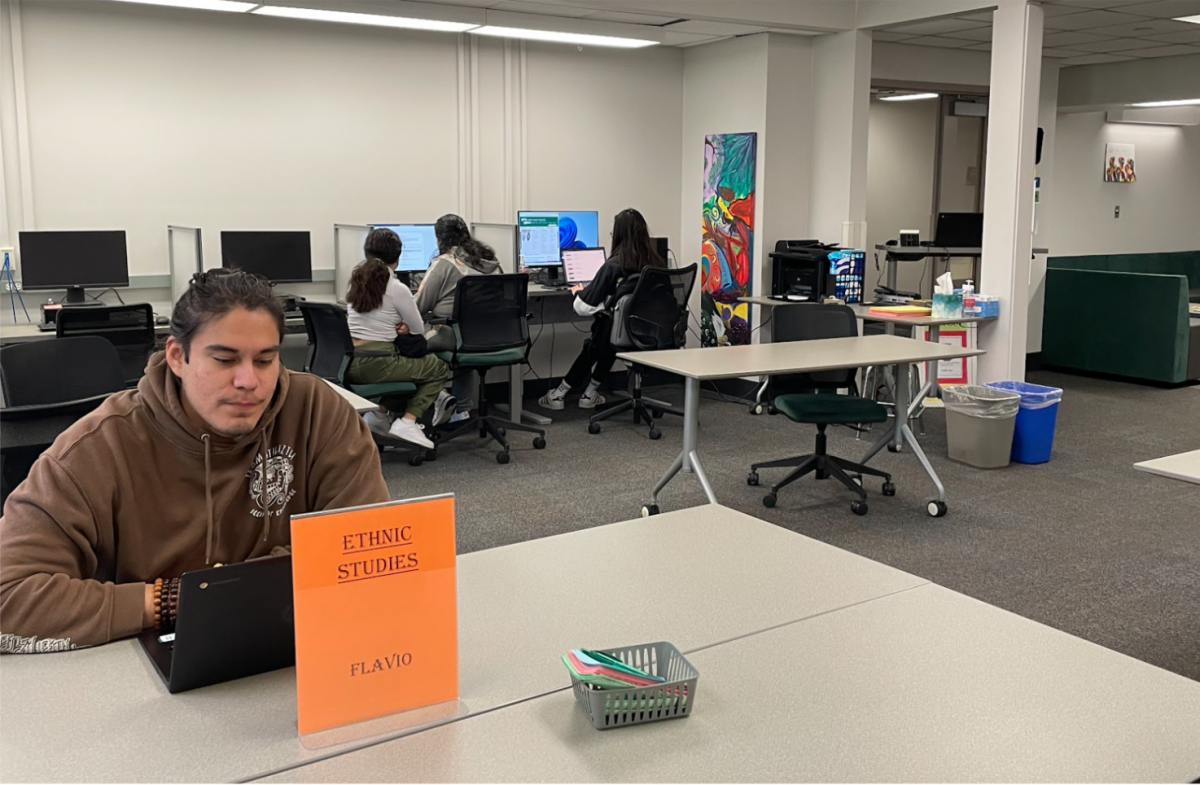

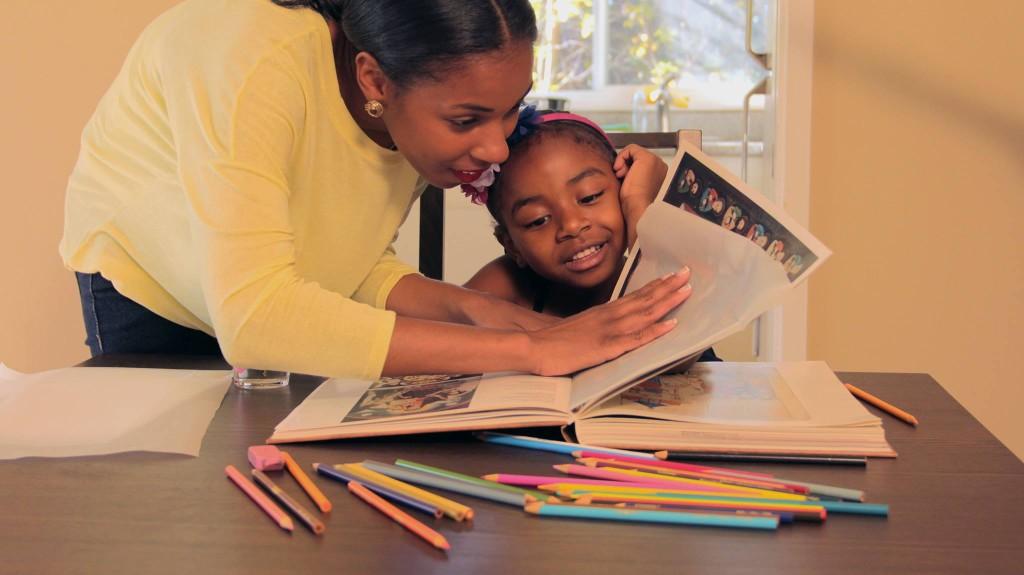

Shonte Johnson and her daughter, London, on the set of “Tracing Paper.” London is Shonte’s youngest of daughter of three. Courtesy of Sureya Melkonian.Photo credit: Julian Mark

December 11, 2013

The film begins in a quiet, sunlit house, with a little girl tracing a picture.

The voiceover of her adult self says, “Did you ever trace something you couldn’t draw because you wanted to be a virtuoso?”

After the girl finishes tracing the picture, she tears the original picture to pieces. The girl holds her tracing up to the light. “I’m a genius,” she whispers.

She grows up to be a successful graphic designer. As she stands in an art gallery subtly eyeing a man, her voiceover explains that she traces her victims with her mind, lures them into her dungeon, and then scraps them just like the original pictures she traced in her childhood.

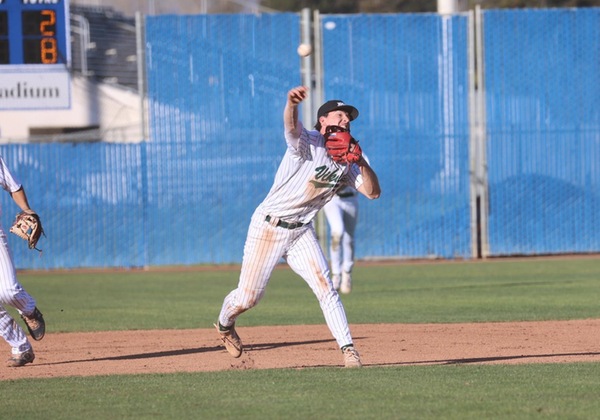

The film is called “Tracing Paper.” It was a finalist at the Berkeley Campus Moviefest, its two lead actresses are Shonté Johnson and her youngest daughter, London. If Johnson is asked if she has anything in common with the character of “Tracing Paper,” she shakes her head and says, “The whole point is to become someone else.”

Shonté raises two other girls, Brejea and Solé. Between her job as a model and her classes at DVC, Shonté supports her three daughters on her own.

“I have to do everything—literally,” Johnson said, chuckling. “I get up, take everyone to school, go to school myself, go home, cook, clean, maintain them [her daughters]. It’s nonstop.”

Johnson first became a mother at 17 when she became pregnant with Brejea. She lived in a small one-bedroom apartment in East Oakland with her mother, who struggled with mental illness and who, according to Johnson, was physically and psychologically abusive, often padlocking Johnson in the house from the outside.

“Part of the reason I became a teen mom was because it was a so unhealthy at home,” Johnson said.

To avoid her mother, Johnson would wander the East Oakland streets, eventually meeting Brejea’s father. When Johnson told him she was pregnant, Brejea’s father threatened to withhold his support if the baby was a girl, urging her, along with Johnson’s mother, to abort the child.

Johnson’s uncle, Michael Hall, remembers Johnson running to his house, tears down her cheek, crying, “I don’t wanna get rid of my baby.”

Feeling unsafe with both her mother and her boyfriend, Johnson moved in with her uncle. After the baby was born, Johnson went back to school to earn her high school diploma.

“I watched her get up every morning, bring her daughter to school, hit the books, and then catch the bus again to pick her daughters back up,” Hall said. “It’s really hard to explain in words the struggle I’ve seen her go through.”

Two years later, Johnson met the father of her other two children. He was a linebacker for Laney College, and Johnson was immediately attracted to his bankrobber-like appearance. Like her first boyfriend, he was abusive, such that Johnson filed a restraining order against him. “He was a mean dude,” Hall said. “I told her, ‘You need to find someone to be good to you.’”

Johnson has done various jobs to support her children, working at Wells Fargo, opening her own daycare, and modeling. But she wanted to finish college. In 2010, she enrolled at DVC and first met Paula Stanfield, a DVC Extended Opportunities Programs and Services (EOPS) counselor, who identified with Johnson’s struggles and worked with her to apply for scholarships and schools like UCLA and UC Berkeley.

“She inspires me,” Stanfield said. “For her to survive in really harsh conditions, basically raise herself, and pull herself out of extreme poverty, to pursuing her dreams is very inspiring.”

Johnson holds a 3.7 GPA and has been award several scholarships. She’s a representative at the Pan African Union and participates at the Inter Club Council. After she transfers, she plans to take sociology and psychology courses, which would further her goal to open a nonprofit for those with lives and backgrounds similar to her own.

“There’s a belief that if you’re an adolescent parent you’re going to stay on welfare or never succeed,” Stanfield said. “She’s breaking all those myths and barriers. She’s definitely a role model for other adolescent parents.”

Johnson was the keynote speaker on panel addressing adolescent motherhood. Even though Johnson admits motherhood is extremely difficult, she doesn’t treat it as a burden. Johnson recently wrote on Facebook, “My daughter made a me a late breakfast in bed. Pancakes, eggs, turkey bacon, and eggnog. #blessed #appreciated #proudmama.”

Still, raising three daughters and going to school, Johnson needs an outlet. Taking her first acting classes in 2010, Johnson has already landed principal roles in student films, most recently “Forget-me-knots” and “Tracing Paper.” She’s appeared in a couple web/television series including “The Dirty” and “Wives with Knives”— and has done commercials for California Medical Weight Management and Alameda Health Services.

“When I’m acting I’m not thinking about my personal life,” Johnson said. “I’m thinking about who I’m playing. I’m acting. I’m pretending.”

Growing up, Hall would tell Johnson, “Shonté, this is the real world, not a fairytale world.” Johnson’s fairytale world has always been to attend college, have a career, get married, and have a house with a white picket fence, a dog and a cat. “That’s always been in my mind,” she said. “Of course it’s still possible. It’s what I make it.”

Johnson explained: “Every morning when I drive to school there are two options. If I take option one I’ll avoid all the craziness of Oakland. But if I take the other option, I will see prostitutes, people on drugs — young and old — spread out on the sidewalk. I’ll see poverty, gangsters and thugs; and when you’re around that all the time — if you let it affect you — you can be a product of your environment.”

When asked if she was a product of her environment, Johnson quickly responded, “Heck no. I’m the exception.”

Editor’s Note: Upon first publication of this article, Paula Stanfield was incorrectly identified as “Paul Stanfield”. We apologize for this mistake.

Mia Stageberg • Jul 5, 2015 at 6:16 pm

I really like this piece. It gives me the feeling that the woman could be a neighbor I’m talking to and I’m behind her in what she’s doing.