Why Intersectionality Matters: Rainbow Community Center Sparks Dialogue About Sexism, Racism and Sexual Identity

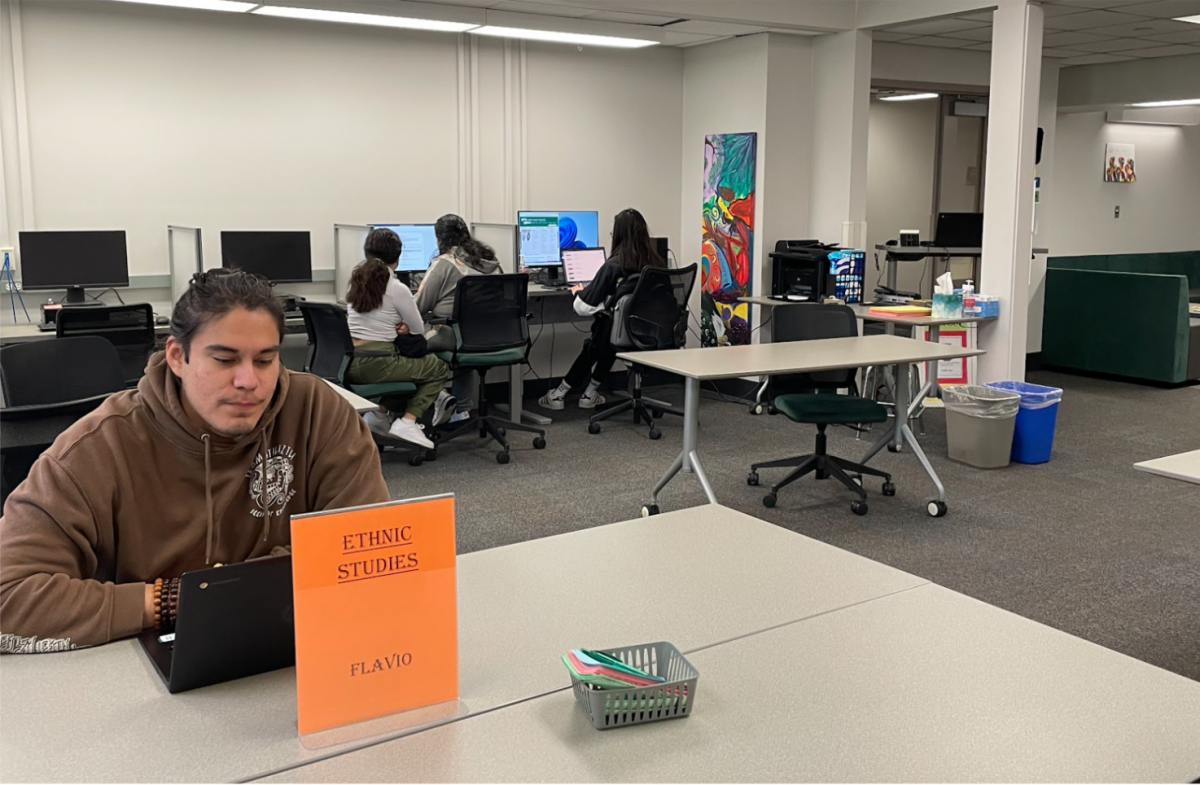

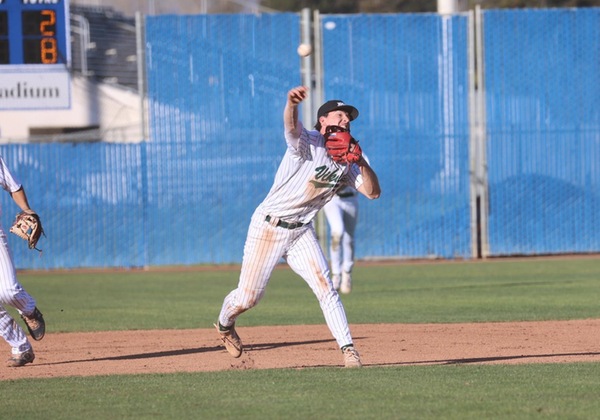

Rainbow Community Center Sparks Dialogue About Sexism, Racism and Sexual Identity (Photo courtesy of Diablo Valley College).

March 3, 2020

In 1976, Emma DeGraffenreid and several other African-American women sued General Motors for employment discrimination, arguing that the company segregated the workforce by race and gender. At the time, white women were the only people at GM considered for secretarial jobs while African-American men worked predominantly on the factory floor.

The plaintiffs sought equal employment opportunities for African-American women at GM. Ultimately, the DeGraffenreid vs. GM Assembly Division case was dismissed when the judge ruled that General Motors could be sued for sexism or racism – but not both.

“The law was like the ambulance that shows up and is ready to treat Emma only if it can be shown that she was harmed on the race road or on the gender road but not where those roads intersected,” said Kimberlé Crenshaw, an African-American scholar, speaking in a 2018 Ted Talk shown at last week’s Brown Bag workshop on intersectionality.

Crenshaw, who teaches critical race studies and constitutional law at University of California, Los Angeles, coined the term intersectionality in 1989, explaining how different social identities relate to systems of oppression and discrimination.

The Feb. 20 event at Diablo Valley College, hosted by Niq Muldrow, a youth outreach coordinator, and Rae Messer, an associate clinician at Rainbow Community Center of Contra Costa County, explored how intersectionality affects marginalized groups and contributes to social justice issues, including sensitivity towards people’s sexual identities.

“There’s so many different factors of who we are as people that impacts how we show up and are treated in the world,” said Muldrow, 21, a former DVC student now studying at Laney College.

Some examples of intersectional social identities are race, religion, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. The term intersectionality entered the public sphere in the 1970s when African-American feminists called out the lack of black representation in the white feminism movement, particularly around issues like sexual assault and low wage labor.

The Combahee River Collective, named after Harriet Tubman’s 1863 river raid that freed 750 slaves, brought together African-American feminists like Barbara Smith, Florynce Kennedy, and Alice Walker who reframed the debate.

“Only from that position of experiencing all of these different intersections can someone speak to what that’s like in the world, versus maybe somebody else who doesn’t hold all those intersections,” said Messer. “It’s a place of power and wisdom that allowed them to create this frame.”

More recently, she said, sexual orientation has become an additional factor in people’s identity and the LGBTQ movement is more recognized and accepted.

Laws prohibiting homosexual activity have been struck down and gay marriage is now legal in all 50 states. Nonetheless, for many people, asking about another person’s sexual orientation is difficult.

“We’re all different and some people take things personally. I don’t want to come out wrong or ask the wrong questions, so I’m kind of mindful as to how and when I ask (people),” said Faustina Ikwudinma, a nursing student at DVC. “I wouldn’t ask anyone if they’re gay if they don’t come out to tell me… because I don’t want to upset them in case (they’re) not and feel offended.”

Messer said it’s acceptable to ask a close friend about their sexual orientation but ultimately, it’s up to the person to talk about their sexuality.

“I think if you’re closer to somebody, asking out of a place of curiosity and wanting to support or connect, sure, but if you’re asking because you’re going to judge someone, then don’t do that,” said Messer.

For Muldrow, it’s best to wait for the person to tell you rather than just asking them, especially if they’re not comfortable sharing yet.

“If they don’t tell you, maybe don’t ask and they’ll tell you when they’re ready,” he said.

As more people become responsive towards oppressed groups, Messer emphasized the need to learn about intersectionality, especially in today’s society.

“It’s important to honor and lift up people’s voices who have been marginalized in multiple ways, so this frame (of intersectionality) is a way to center the voices of people who have experienced oppression or marginalization in many different ways,” she said.

One of the best ways to be informed about social problems, according to Muldrow, is to join organizations such as the Family Justice Center or Bay-Peace.

“There’s so many resources out there, activists, community organizers. It’s just a matter of people taking the time to access that,” he said. “I think we all owe it to each other to really be more informed about these issues because if we don’t have all the information, it’s hard to find all the answers.”