For International Students at DVC and Across America, the Coronavirus Presents A World of Crises

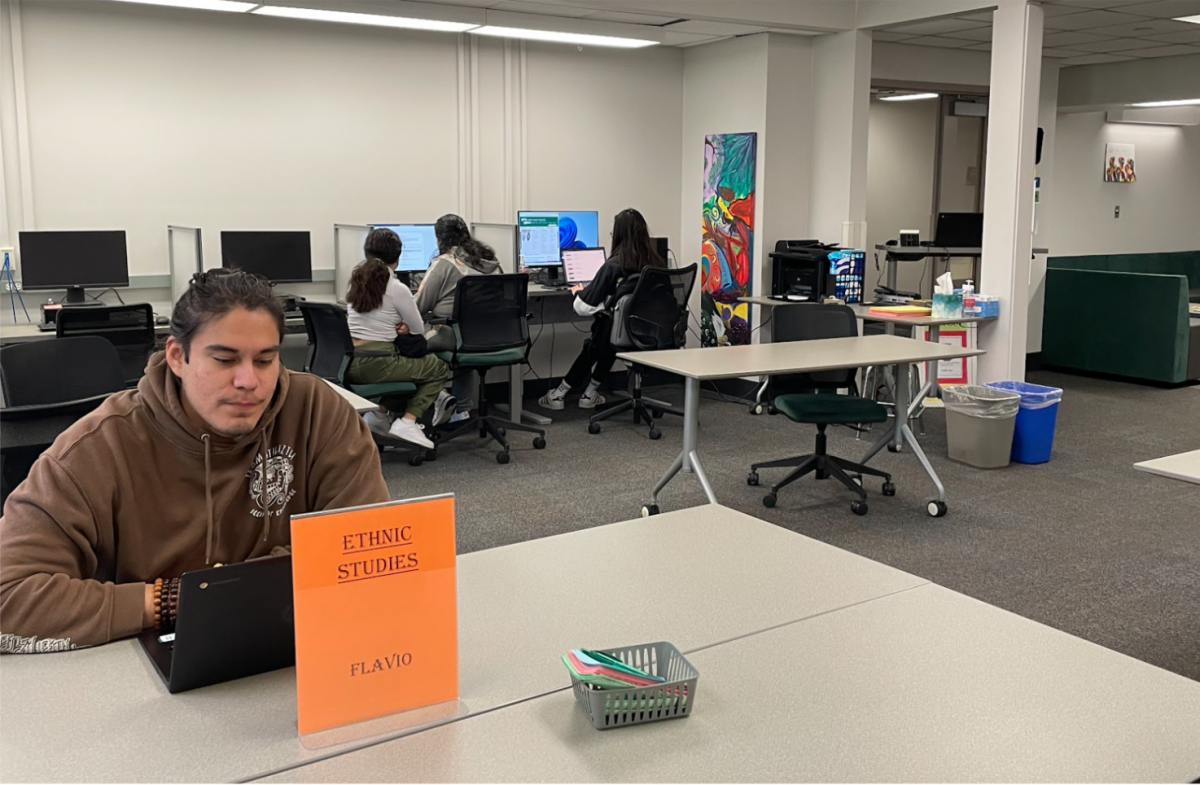

Coronavirus creates many extra challenges for international students at DVC and across the U.S. (Photo courtesy of The Conversation)

May 2, 2020

Being an international student in the United States never posed so many challenges.

For the first time since World War II, having a pantry full of bread and pasta is considered a privilege across this country. Personal hygiene items such as toilet paper, hand soap and hand sanitizers are being fought over by panic-stricken people in supermarkets. Both online and in-store mask prices are being marked up more than tenfold the original price. People of all ages are forced to stay home as essential workers fight on the frontlines, tired and overworked. Weddings, funerals and concerts have been canceled while schools have changed from in-person to online classes in an incredibly short time. To top it off, more than 30 million Americans have lost their jobs due to the pandemic in the past six weeks.

As of the fourth quarter of 2019, more than a million international students were studying in the U.S. Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic approaches the three-month mark since first being classified by the World Health Organization as a global health emergency, many foreign students say they are devastated and going through what could be called the rock bottom of their lives.

Seita Fujiwara, an international student from Japan studying computer science at Diablo Valley College, is one of the tens of millions of people nationwide facing unemployment due to the crisis. Fujiwara worked at the DVC cafeteria, which has been closed since classes moved online in March.

“No more job, and no more salary,” said Fujiwara. “I usually buy groceries with money that I earn because I do not want to burden my parents.”

But financial troubles are only a fraction of the current crisis. Many international students are also facing racism, visa complications and eviction from on-campus housing at the institutions where they are studying.

“I feel emotionally drained and restrained,” said a second-year DVC communications student from Indonesia, who preferred to remain unnamed.

A DVC alum who is currently working on her bachelor’s degree at University of San Francisco also voiced concern about discrimination against international students since the outbreak of the virus.

“At this moment, living in the Bay Area as an international student is really hard. We now, more than ever, have to handle discrimination and racism,” said the student, who also preferred to remain unnamed.

She added that her concerns about racism increased when her friend, who also lives in the Bay Area, was harassed while taking a jog at Ocean Beach soon after the pandemic news broke.

In addition, due to the pandemic, the USF student had to abandon her years-long plans to work in the United States and will instead go back to her home country immediately after she completes her bachelor’s degree in May.

“It is almost impossible to get a call back (after job interviews) in this pandemic, let alone be approved for Optional Practical Training,” the temporary employment opportunity for F-1 visa holders, she said. The OPT would have granted her another year in the U.S. and potentially a work permit in the future, but now those plans are off the table.

However, the student said USF’s fast and effective response to the pandemic paid special attention to the well-being of international students like herself, and it shed a light of hope. The institution was able to perform a quick, organized procedure to contain the pandemic within its on-campus housing, while providing support needed for students to relocate as well as expediting the F1 visa travel approval process for international students who wished to return home.

Things are a bit different in the Midwest. A 19-year-old anthropology major from Indonesia, studying at Wheaton College in Illinois, said she isn’t feeling as lucky as some of her student counterparts in California. Despite its stereotype as “the Harvard of Christian schools,” she said Wheaton was neither quick nor effective in responding to the global health emergency.

She and her friends who live on-campus said they were only notified of the campus closure in mid-March. Wheaton strongly suggested that international students move into families’ homes, she said, because of worries that the school wouldn’t be able to adequately take care of them during the crisis.

“Just the realization that I have to leave (the campus) was so scary. I was panicking and confused,” said the student, who preferred to remain unnamed.

The student added that some of her Wheaton colleagues had to pack their bags three to four times moving from one place to another, all while juggling school work.

Shortly after packing up, she moved to a friend’s home in Morton, Illinois, two and a half hours south of Chicago. But her doubts have since only magnified.

“Now that I have moved, my biggest anxiety is, where do I go now? What do I do now that the semester is ending? Is it wise to go home? But if I go home, I might either get the virus or help spread the virus and kill more people.”

Editor’s note: This article has been translated into Indonesian, without The Inquirer’s permission, and republished on numerous news outlets across Indonesia, including Yahoo Indonesia.

As a result of the poor translation and the Indonesian media’s effort to sensationalize this story – for example, by taking quotes out of context, and by over-dramatizing the experience of some Indonesian students in the Bay Area and the Chicago area who expressed concerns about increased xenophobia amid the Coronavirus pandemic – we have decided to take those students’ names out of the story in order to protect their privacy. Some statements and details have also been updated to more accurately reflect those students’ experience.