“Things Got Really Tough and the Desire to Drop Out of School Was Overwhelming”: The Pandemic Hit Students Hard, But It Hit Foster Youth Students Even Harder

March 23, 2021

As the coronavirus pandemic forced closures across the state last year, and thousands of students struggled to stay enrolled in school, foster youth faced even more severe challenges.

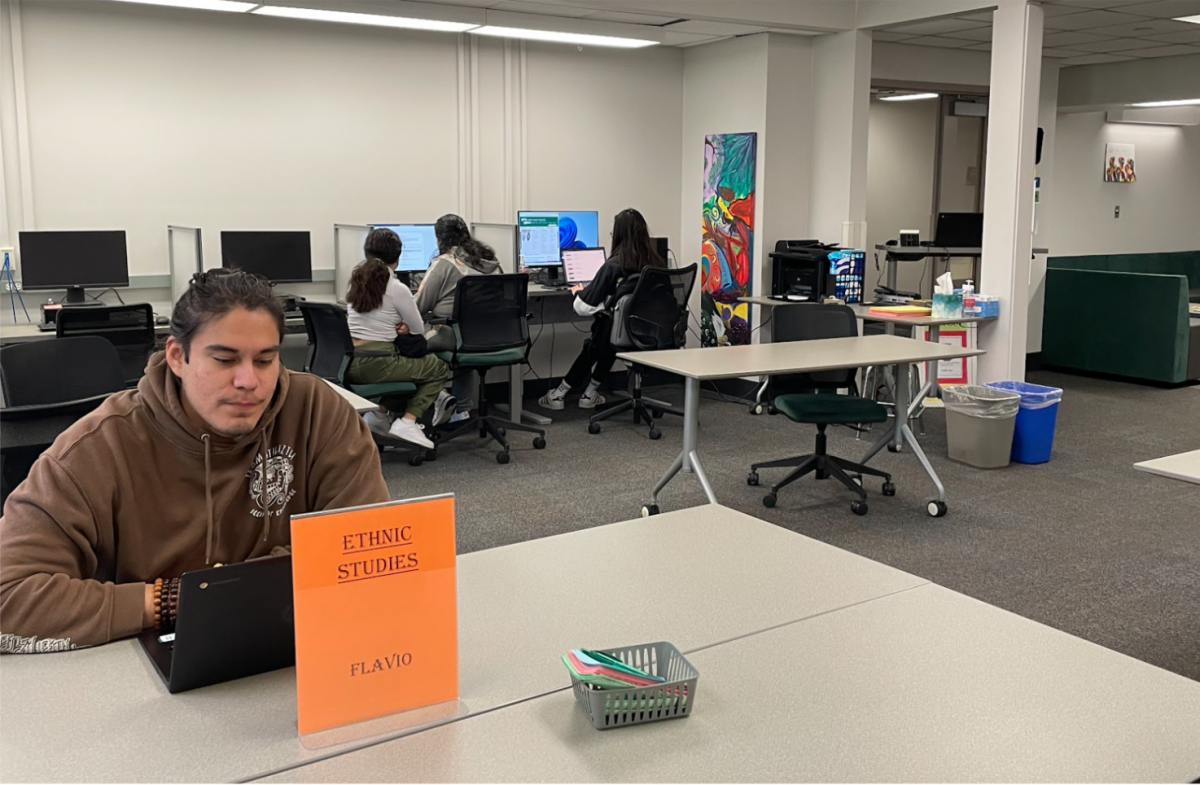

“Things got really tough and the desire to drop out of school was overwhelming,” said Trinity Love, a 20-year-old foster student majoring in business with a minor in communications at Diablo Valley College. Over the course of three days last spring, “I lost my job, college, therapy, and mental well being.”

Staying in school was already tough for foster youth before Covid-19 came along. Fewer than 3 percent of foster youth will ever graduate from college, according to The National Foster Youth Institute. Foster care students can often be exposed to four major types of “maltreatment”: neglect, physical abuse, psychological abuse and sexual abuse. All of these can be contributing factors in low graduation rates.

Foster Focus magazine reports that approximately 400,000 young people are currently in foster care in the United States – and that about 20,000 of them age-out each year from the foster system without positive familial supports or any family connection at all. Within 18 months of emancipation, 40 to 50 percent of foster youth become homeless.

The stress of Covid-19 and the lack of community couldn’t have come at a worse time for Love. After being removed from her home in 2015 and relocated to the East Bay, she was rebuilding her life, living in a safe environment and enjoying her job in retail. But the coronavirus put an end to the few securities she had in place, making it impossible for her to focus on education.

“Once Covid hit, I gracefully took a D- and dropped one of my classes. In order to compensate, I took two accelerated courses over the summer to stay on track,” Love said.

But to make matters worse, “I was living in transitional housing [provided for foster youth] and I was randomly placed with an abusive roommate. The violence brought up issues from the past making it impossible to concentrate.”

Since the pandemic began, community college enrollments have plummeted 10 percent nationwide but statistics for foster youth are far worse. According to DVC, one-third fewer students than last year are now participating in the school’s Student Transition and Academic Retention program, or START, which is designed to support foster youth as they transition into college.

“Foster youths have specific challenges that are not easily remedied. They arrive at DVC with educational gaps and the reality of the work involved is daunting,” said Mercedes Lezama, who has worked as the director of the START program for the past five years.

“Add trauma, isolation, lack of family, no transportation, food insecurities and, in some cases, homelessness,” she said, “and the challenges become even more daunting.”

Lezama learned through her own firsthand experience the benefits and importance of finding critical resources when they’re needed. While still in high school, Lezama learned she was pregnant, and as an unwed mother with no financial support, she made the bold decision to enroll at DVC.

Like the foster youth students she now serves, Lezama was ill prepared for the rigors of college life, and credited the early support she received from Student Services Instructional Support coordinator Dona DeRusso for her success at DVC.

“DeRusso told me all about the CalWORKs and EOPS/CARE programs and how [they] could help me and my child,” said Lezama, who was awarded Student of the Year honors at DVC in 2010, and later graduated from Mills College with a sociology degree. “Had I not been involved with those programs, I don’t believe I would have lasted in school.”

Years later, Lezama continues to help other students in crisis, like Love, to find their way. But the virus has posed new difficulties, she said, particularly in the realm of building in-person relationships.

Offering emotional and verbal support through consistent face to face contact is crucial for developing connections with foster students, Lezama explained

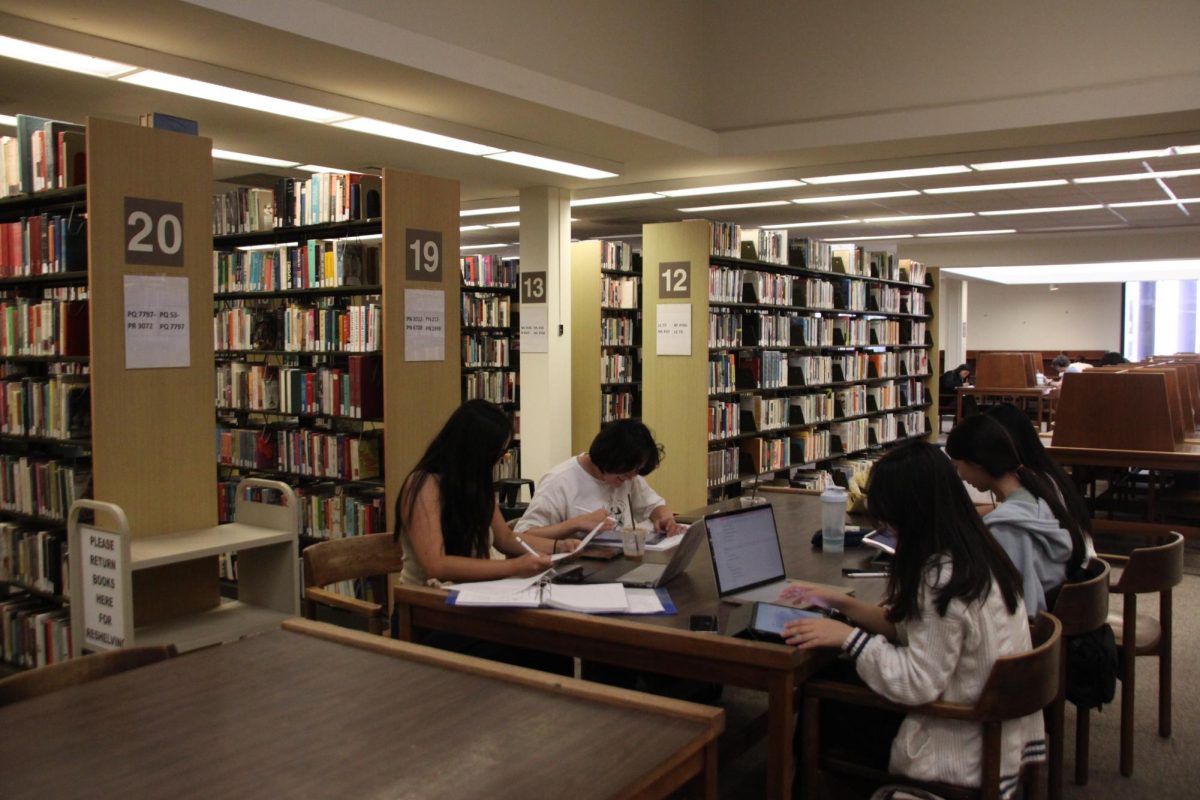

“Zoom is not conducive for building rapport, and without it, these students are cut off from essential services,” she said. “Online education simply isn’t enough, and the most devastating impact has been the loss of community and social connection.”

For Love, the experience of the school’s closure last spring had both immediate and far-reaching impacts.

“Once DVC shut down, I felt isolated and alone. I wasn’t able to visit the START offices to see Mercedes and my education suffered,” Love told The Inquirer.

Among other disadvantages to the online-only curriculum, attending asynchronous classes don’t allow Love to build friendships or establish camaraderie with fellow students. She said she misses being in the classroom where she can bounce ideas off other students and learn from her peers.

Love admitted, “I wish I didn’t have challenges, but I do, and I am honest with myself. I see a lot of kids come and go in the program. They try so hard, but their priorities aren’t straight.”

For this reason, she added, guilt also plays a part in the overwhelming pressure she feels to succeed. “Sometimes I fear I am taking up space and time from another student,” Love said. “Whether it’s a class or within the foster youth program, I know I have been given an opportunity and I don’t want to blow it.”

Love credited the support of the START program – and specifically her relationship with Lezama – for helping to keep her enrolled at DVC through two challenging semesters amid the pandemic.

“I am grateful to Mercedes for being so wonderful and encouraging. At every meeting, she will ask me how I am doing and goes out of her way to help me,” Love said. “She doesn’t just point you in the right direction: she physically walks you to offices on campus that provide support or makes calls on your behalf for any other issues.”

On one occasion, Love recalled, Lezama went above and beyond. Love had just had her car window smashed and her laptop stolen. She went to the START office, where Mercedes spent hours helping her find a local auto shop that would fix her window at a discount, and tracked down a temporary laptop to loan her.

Lezama said she is grateful for Love’s continued participation within START, but is extremely concerned about the foster youth that are no longer in her program. She said, “These kids have suffered trauma and without direct support they are our highest risk population.”

One of Lezama’s main goals is to teach foster youth how to become “trauma informed.”

“You can’t heal from trauma if you don’t know how to identify it,” she said. Therefore, “the first step is to understand adverse childhood experiences,” or what she called ACES, “and how they impact the student in the present day.”

More recently, Lezama has received $50,000 in grant funds to head up a pilot program called START Scholars. She will follow the progress of 10 selected foster students, providing them with books, supplies, transportation and a $100 stipend each month along with mandatory workshops on self care and career advice. Through the program, Lezama said she will be better able to determine whether specialized targeted assistance improves success rates for foster youth.

Lezama has been working closely with Love to help her fulfill her dream: transferring to a California state college and earning a degree in business with a minor in communications. In the meantime, she eagerly awaits the reopening of the DVC campus.

“We don’t have a lot of funding,” Lezama said, “but we have a lot of heart.”