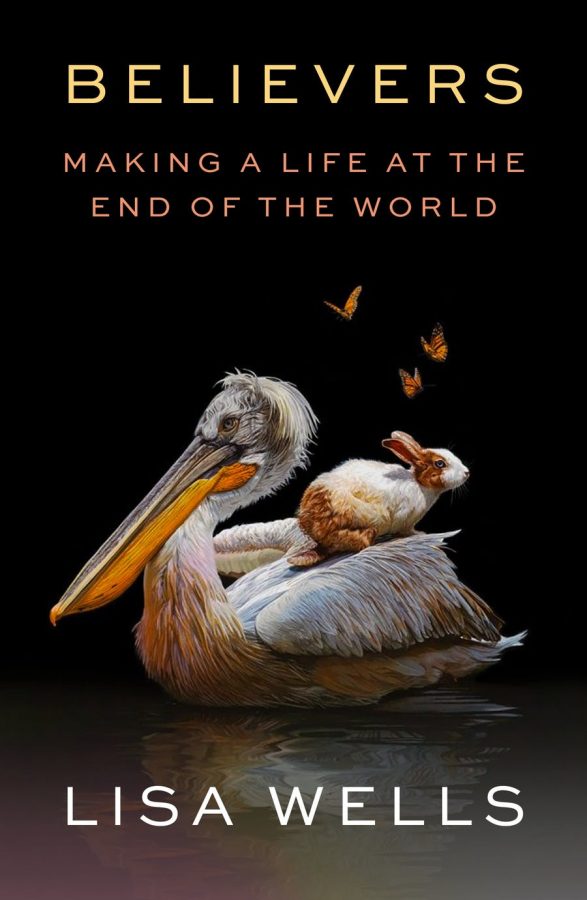

“How, Then, Shall We Live?” Author Lisa Wells, in “Believers,” Discusses Prospects at the End of the World

December 6, 2021

In the midst of a climate crisis that has brought devastating wildfires, drought and harm to many of the planet’s natural species, author Lisa Wells asks: “If the Earth is our home, if our home is being destroyed—how, then, shall we live?”

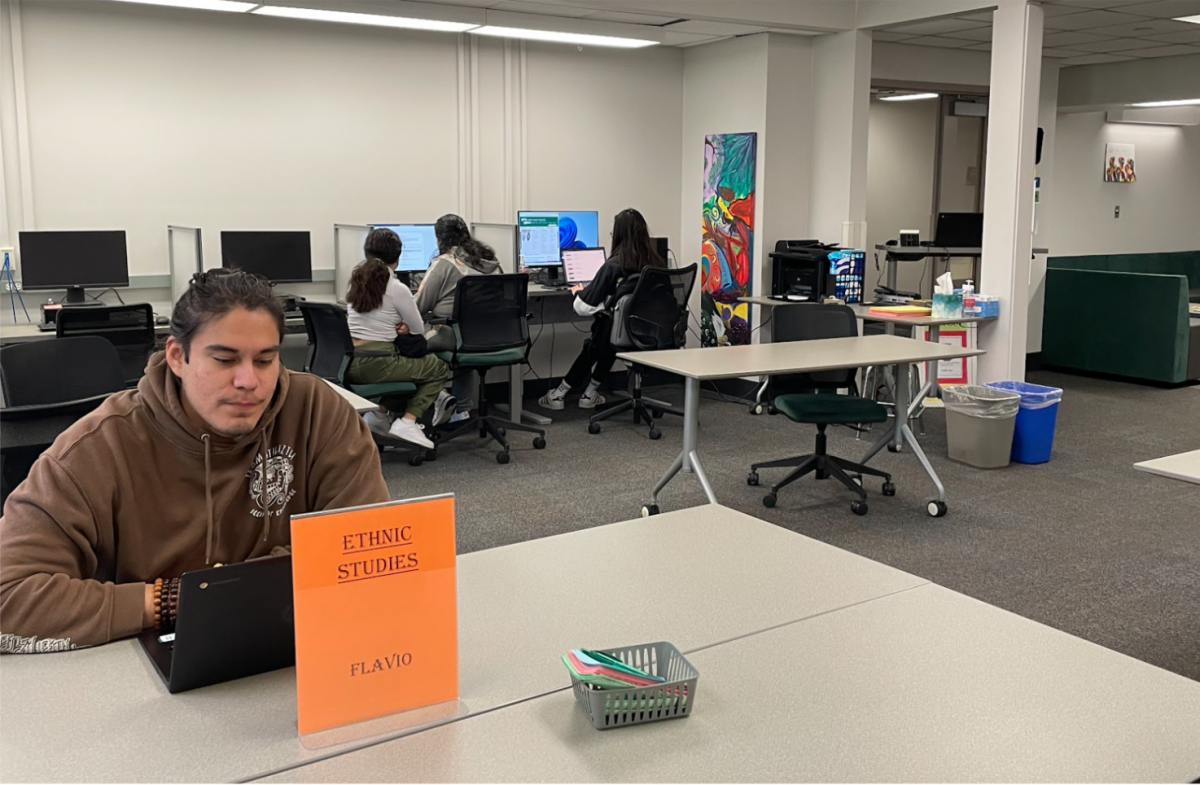

An Iowa Poetry Prize-winning poet and nonfiction writer hailing from Portland, Oregon, Wells discussed her recent book Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World during the latest installment of Diablo Valley College’s virtual Journalism Speaker Series on Nov. 18.

Described by DVC social science and history professor Mickey Huff as possessing “captivating storytelling skills and wordsmithing,” Wells explained her book as a personal story that became a pilgrimage in which she encountered many different people forging a bold approach to the future. She recalled reading a few books around the ages of 14-15 that helped open her eyes to the “inherently hierarchical, unsustainable, and doomed-to-collapse” world that she was born into.

“As a kid, a lot of alarm bells were going off, and me and my little cohort of friends dropped out of high school [and] ran away to a wilderness survival program to try to acquire the skills necessary to form egalitarian communities on the frontier of the post-apocalypse,” Wells said.

She spoke of the disillusionment she had felt about what she wanted in her youthful desire to save the world, and her inability to achieve those goals.

Wells ultimately turned to writing, which she called “probably more in tune with my actual interests, as opposed to my idealism.” Fifteen years after the onset of her awareness, Wells had gone to graduate school and returned to the dilemmas posed in her younger years.

Believers is the result: a moving story about humanity seeking ecological restoration and revival.

In her talk, Wells displayed a slideshow of photographs showing some of the people she had met along her journey, and shared their stories told from the fringes of society. Her high-school best friend, who remained on the “wilderness survival” path into adulthood, dedicated himself to learning “pan-cultural, pre-agrarian” ancestral skills such as basket-weaving and how to craft clothing, she said.

Wells also shared a photo of a woman she had met who had lived off the grid for forty years, nomadically, and had devoted her life to replanting and tending edible and medicinal flowering tuber plants. She described the woman as a “very divisive, potent character” who believed that those who take from the Earth without giving back are sinners.

While visiting the woman’s camp, Wells was introduced to the concept of reciprocal land management and the idea of “abundance through disturbance,” the latter being when plants flourish with human and animal consumption and relocation, which helps to spread their seeds and aerate the soil in which they grow.

“Basically, every being on the planet is serving some ecological niche, and human beings are no different,” Wells said, pointing out that squirrels garden when they bury acorns that grow into oak trees, and bears and birds plant berry bushes through the scat they leave behind. This, Wells said, is at the heart of reciprocal land management.

She emphasized the difference between the branch of “rewilding” that focuses on the hypermasculine “get buff and run barefoot” emphasis on one’s body, and the branch that is more contextual and ecological, focused on “[undoing] our dependency on these systems that are bringing about the collapse of the biosphere.”

Wells spoke of her interaction with environmentalist Christians, who referred to themselves as “radical disciples.” These people live in community, share resources in common, repair the earth, and live in close connection with the soil, Wells said, and “atone for historical atrocities done in the name of the church and practice something they call ‘resurrection work.’”

She also discussed the concept of transition towns, where people live as though the economy based on oil has already collapsed. The towns try to source their own food and water and use a barter system economy.

Wells described a “mutual aid society” in Philadelphia, where residents displaced by economic hardships have collectively rehabilitated foreclosed and condemned homes for community member ownership. The society also focused on rehabilitating the toxic soil of a former factory site within the neighborhood to develop the land into a park for community use.

She referred to the revival of these sites as “[metabolizing] the cultural shadow.” The community also melts down firearms and uses the metal to forge gardening tools.

Wells said she was introduced to the concept of sabbath economics by members of the mutual aid society, which, “in the old dictates of Sabbath,” involves people giving their lands a rest every seven years, freeing people from debts, flattening hierarchies and redistributing wealth. According to their beliefs, culturally imposed limits to growth keep the land and ecosystem from being overtaxed and keep society equal.

Likewise, to live in sin means to live in a manner that pollutes the environment or takes more away than you give back. Repentance in these Christian communities amounts to more than an apology—it involves changing and living in a new way, Wells explained.

The author spoke of how cooperative community has been the norm for human history, saying that the “modus operandi of the culture has been to, in some ways, inactively or actively, dismantle kinship networks that help people to not have to work three jobs and to feel supported, fed and clothed, and [that] your kids are taken care of.”

Upon meeting professional tracker Fernando Moreira – known as the Portuguese Sherlock Holmes because of his “supernatural” ability to track animals and people across different types of terrain – Wells learned that “you don’t have to be perfect to have a relationship with your ecosystem, but you do have to keep showing up.”

She said she views tracking as a practice of attention, as one becomes intimate with certain locations at different times and during different weather conditions, calling it a way to overcome the disconnection and lack of understanding people often feel in nature.

At one point, Wells visited a meadow in the Sierra Nevada that had historically been a gathering place for a Native American tribe, but over time became choked with brush growth and garbage. North Fork Mono Tribe elder Ron Goode, along with his tribe and the U.S. Forest Service, worked with a group of volunteers to clear out the trash and set a low-intensity cultural burn to clear the meadowland area.

Fifteen years on, Wells said, the meadow has been restored, with 100-150 different species of animals and plants returning to the land.

“The focus is the foundational myths of the culture I was born to and trying to undo them in myself,” Wells said of Believers. She began working on the project in 2014, not thinking she was writing a book at that point, but “slowly, that’s what it became,” she said. “I actually had this experience where the book changed me. The people I talked to changed me.”

Wells emphasized collapsing the abstraction between humans and nature by taking a moment to look around at the natural world and absorb it.

“It’s just about awakening to the other lives that are around us all the time.”