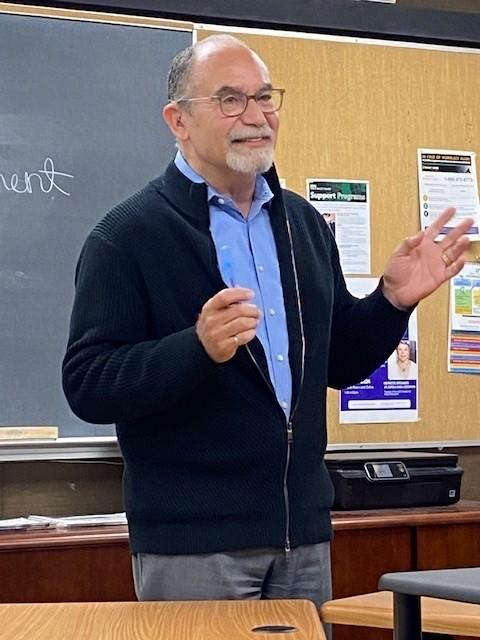

Renowned Chicano playwright and film director Luis Valdez delighted a room full of Diablo Valley College students and faculty on April 17 with his humorous anecdotes that offered insight into the importance of creativity, community, and theater.

Valdez wrote Zoot Suit (1978), the first Chicano play to reach Broadway, based on the Sleepy Lagoon Murder Trials and Zoot Suit Riots that shook Los Angeles in the 1940s.

The pioneering bilingual play criticized how the city of Los Angeles used the Pachuco subculture to stereotype Mexican-American youths as delinquents.

Valdez, who also wrote and directed the Ritchie Valens biopic La Bamba (1987), prefaced his talk by stressing the importance of honoring Latinx heritage.

“As Mexicanos, as people of color, as indígenas, as women, as farm workers, we have been sold a bill of goods, that we have no real heritage, that we are culturally deprived, and that we have no background,” Valdez announced. “That is a lie meant to keep us in our place.”

“We’re coming to the majority of the state [population], and that freaks out a lot of people, but we were here before,” Valdez said. “We were here before, and as indígenas, we were here before that!”

“So in a way, we’re rooted in California. We’re not strangers. We’ve been here for ten thousand years. We’ve been here for twenty thousand years. We’ve been in America because we are America.”

A balloon, a monkey and a truck, oh my!

Valdez was born in a Delano labor camp in 1940 to a family of Mexican-American farmworkers.

Reflecting on the power of childhood experiences, Valdez recounted visiting the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk with his family at age six as a reward for the productive harvest season.

At the boardwalk, young Valdez marveled at a red helium balloon his father bought him, but a moment later, he distractedly released it to grab the hotdogs his mother just handed him. His parents couldn’t afford to replace the balloon, so he was left watching it float away.

“It was painful,” Valdez recounted, looking up at the ceiling and pantomiming as he spoke. “All I could do was bite into my hotdogs, and watch my balloon go up into heaven.”

“I learned a very important lesson that day, and it stayed with me all these years: that if you’re real careful, you can have your dreams and eat them too.”

The audience laughed, but Valdez continued with sincerity.

“And that’s really important. Respect and honor your dreams. Don’t give them up. Fight for them, achieve them. This is what motivates you.”

Another time, Valdez recounted, his father’s car broke down at the end of the harvest season and his family found themselves out of work. Since they “lived from hand to mouth,” his family would fish the San Joaquin River for their dinner.

“We were eating fish tacos before it was trendy,” Valdez joked.

But one day, Valdez almost drowned in the river, prompting his mother to enroll him and his older brother in a nearby school.

Each school day, his mother would pack him tacos for lunch in a little brown paper bag, which Valdez said became a source of embarrassment as he compared them to the ham and cheese sandwiches the Anglo kids ate out of their lunch pails.

“Me dió pena, you know?” Valdez said. “I was ashamed of my little taco bag and my mama’s tacos.”

Then one day his lunch bag went missing and Valdez found, to his astonishment, that his teacher had used it to make a paper mache monkey mask for the school play.

When the teacher offered him the role of a monkey in the performance, 6-year-old Valdez was ecstatic.

He said he has valued this memory throughout his life because it introduced him to “one of the secrets of the universe,” the art of transforming something as commonplace as a paper bag into any shape imaginable.

“I don’t know if [my teacher] ever realized what she had done,” said Valdez. “She launched me on my career. She gave me the raison d’etre of my life. She turned me into an actor, and as a consequence into a playwright and into a director and into a filmmaker.”

“It all goes back to that childhood experience, the 6-year-old,” Valdez said. “Each and every one of us has a 6-year-old inside.”

“If you maintain your 6-year-old inside of you—your creativity—you can turn it into magic.”

But before the young Valdez could make his “[acting] debut before the world” in his elementary school play, he received news that would put an abrupt end to his plans.

“The week of the performance, I come home from school, and my mom says, ‘We’re leaving [the city] tomorrow… we’re being evicted.’”

Torn away from his first performance opportunity, the young Valdez had trembled with indignation and dismay.

“I’ll never forget feeling this hole open up in my chest. It could have destroyed me,” said Valdez. “The fact is the hole is still there, but for over 75 years I have been pouring plays, poems, music, [and] movie scripts [into it].”

He added, “The hole is much smaller now, but it’s still there.”

Valdez recalled that several years later, his third grade teacher held a class contest that would reward the best-behaved boy with a toy truck.

Eager to secure the prize, Valdez asked to serve as class monitor, but his teacher declined his request on the pretext that the current class monitor was the son of a grower, whereas Valdez was the son of a farmworker.

That day, Valdez stormed off to his grandfather’s shed and began constructing a toy car of his own. With Coca-Cola bottle caps for headlights and tires made out of the tops of mayonnaise jars, the little truck garnered the praise of his parents, who put it on display in their living room.

“I learned then that I could make things with my own hands,” said Valdez. “So the moral of the story is, when in doubt, build your own damn truck!”

Valdez said all of these experiences set him on track for a career in theater, which he later pursued at San José State University.

Theater and Community

After college, Valdez combined his passion for theater with Chicano activism when he joined the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union and founded Teatro Campesino, a theatrical troupe that performed plays and improvised skits to motivate farmworkers to join the UFW and go on strike in the 1960s.

“To satisfy that residual anger that I had as a 6-year-old, I went to Cesar Chavez and pitched him the idea of a theater of, by, and for farmworkers,” Valdez recounted.

“The thing about performance and live theater is that you gather to express the heart of your community, and the ideas that bond us together, the ideas that carry us forward, the ideas that are in fact creators of our community,” said Valdez.

He added that touring abroad with Teatro Campesino broadened his perspective. “You’ll discover that when you go out into the world to do what you must do, there are people all over the world that will connect with you… from all backgrounds, all colors, all languages.”

The support he received from the international community enhanced the already cosmopolitan worldview he said he had acquired from his childhood experiences picking cotton alongside Japanese Americans, Sikhs, African Americans, and Okies.

Speaking from the Chicano perspective, Valdez intoned, “Black liberation is our liberation. Women’s liberation is our liberation. Gay liberation is our liberation.” The audience began to applaud as Valdez continued, “Trans liberation is our liberation. White liberation is our liberation.”

“Tu eres el otro yo,” he proclaimed. “This is the basic Mayan principle we have extracted from our study of Mayan culture. If I love and respect you, I love and respect myself. If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself.”

In line with another principle of Mayan thought, Valdez told the audience to take care of each of their four columns of being: body, heart, mind, and soul.

“Corazón is really important,” Valdez emphasized. “Protect your heart, the things that you love. Don’t sell out; stay true to what’s in your heart.”

He concluded by reciting a poem in three different languages: English, Spanish, and Nahuatl, an indigenous language from Central Mexico. Summarizing the poem’s message, Valdez addressed the audience, “America, raza, my community, my brothers and sisters: find your art, and find the meaning of your life.”

Anthony Gonzales • Jun 21, 2024 at 9:13 am

Thank you for covering this event! Valdez’s talk was truly powerful and I have the video on Youtube if any wants to review it!