Genocide bill kills free speech

February 7, 2012

Two weeks ago, the French senate passed a bill making it a crime — punishable by up to a year in prison or a fine of $58,000 — to deny any genocide recognized by the French government. This includes the Holocaust and, more controversially, the Armenian Genocide.

Due to overwhelming opposition, the bill has been appealed and not without good reason. While it seems to be a good gesture on France’s part to ensure the respect of certain cultures, this bill is a blatant obstruction of the freedom of speech and expression the West constantly prides itself in.

Genocide is another one of those subjective terms that are often misused and taken out of context: what may seem like genocide to one group of people is simply war to another. Seeking to create a universally applicable definition, the United Nations defined genocide as the killing or displacement of a group with the “intent to destroy.” As it turns out, it is finding this intent that makes defining genocide so difficult.

Unlike Hitler, most leaders do not publish their ethnic cleansing plans. With this intent almost impossible to prove, who is France–or any country for that matter–to determine whether or not a conflict is genocide?

If a government chooses to recognize and outlaw the denial of a debatable genocide, then it must also recognize any other ethnic conflict that might be considered as such–including the treatment of the Native Americans in early America, the tragic results of 19th century Belgian colonialism in the Free State of Congo, or even ongoing the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. France itself could be accused of genocide after its brutal treatment of Algerians during their independence movement in the fifties and sixties. All of these conflicts have one thing in common with the Armenian Genocide: not everyone can agree on whether or not they can be defined as “genocide.”

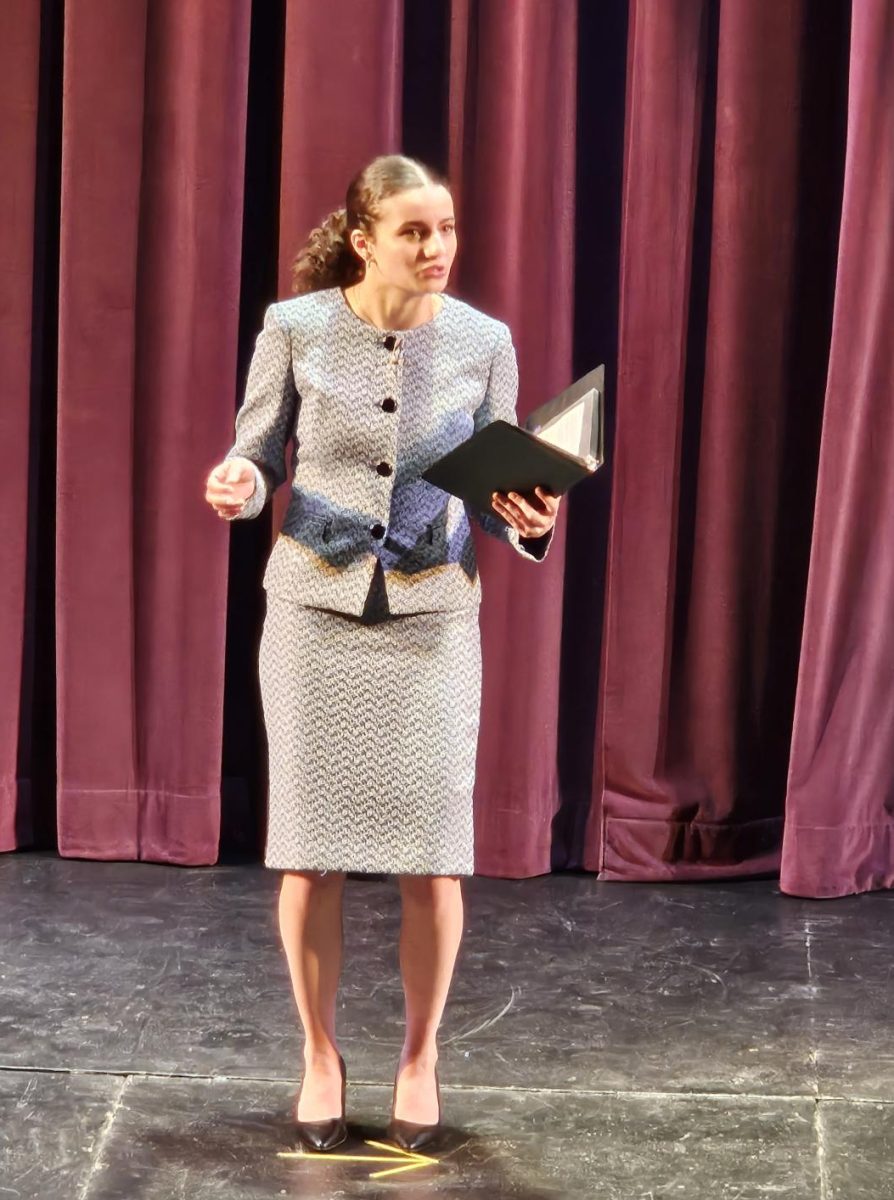

According to Rubina Darakjian, a professor at DVC of Armenian descent, this bill could worsen already-existing tensions between Turks and Armenians. “There has to be a better way of rectifying history without punishing those who either do not understand Armenian history or choose to falsify it.”

While it is important to both acknowledge that there were horrendous crimes committed in the past and to prevent them from happening again, this intrusive bill limits not only opinions of the people, but the research of historians and scholars. It takes away an important part of history, its only never-changing quality: uncertainty.