Editorial: Why we name sources

February 12, 2018

As reporters we are constantly balancing the credibility of our work with the need to protect our sources.

Naming sources gives transparency to articles and allows readers to examine the validity of information for themselves.

Was the source an eyewitness at the scene of an incident? A subject matter expert? My grandmother?

Our job is always to put out the best, most well-represented information we can so people can examine the issue for themselves and draw their own conclusions.

When we don’t name sources we cease to be a pillar of information and instead become an institution that demands our readers trust us on blind faith.

As members of a profession whose first job is to ask “why” in order to learn and share the truth, we cannot expect the answer to our readers to be, “because we told you so.”

When we ask for names and contact information it is so we have a paper trail to lead us back to our sources if we ever need to clarify information given to us or if the validity of our sources comes into question.

That being said, not all sources are named equally.

Good reporting requires always balancing the needs of your audience and those of your story.

Sometimes a story would be better if a source was named but if it means putting the source in danger, that is something we must always take into consideration.

Granted, as a college newspaper our stories rarely elicit the kind of backlash that could bring physical harm to anyone but when working on controversial topics we cannot take any reckless or threatening acts lightly.

This also means considering who may be exposed to such retaliation and what their level of exposure might be.

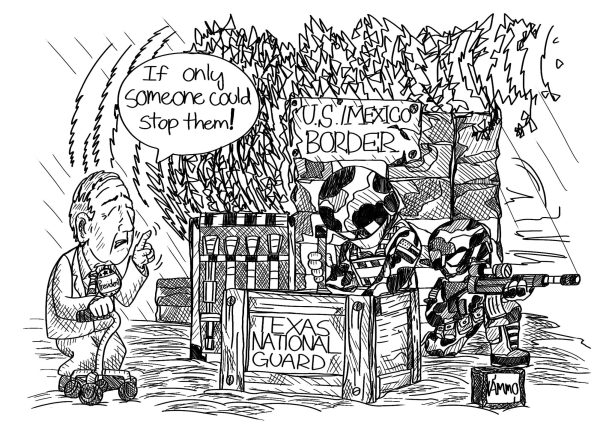

We named professor Albert Ponce when he gave his speech last semester about white supremacy in the United States.

Ponce received a lot of backlash and subsequently had his personal information put out onto the internet, a term called doxxing.

Whether you agree with him or not, Ponce made himself a public figure by hosting a seminar to share his political viewpoints and allowing the DVC Inquirer to film his lecture.

That his message, once public, had unintended and negative consequences comes with the territory of a speaker wanting to use their platform.

On the other hand, we withheld the name of a student at a DACA rally when we learned she was a Dreamer and could be at risk of deportation if named.

This person, though threatened by government action if their identity was exposed, chose to put their faith in us when we quoted them in our story.

While, like Ponce, they gave their opinion on the situation, they would not have done so if we did not ask for their comment first.

We strive to deliver the most complete news to the DVC community by interviewing multiple sources and confirming the information given to us.

It is important to us that you know where we are getting our information and that what we deliver isn’t from a single source or worse, fabricated.

If we don’t do otherwise, we are no better than the comments section on YouTube hiding behind a screen saying whatever we want.

As a paper, our job is to serve you, the community. Without you there are no stories to tell.

Sharing information and shedding light on issues important to DVC only happens when people are willing to speak their truths, however controversial or uncomfortable they may be.

By continuing to speak to us about issues and using your name, you are not allowing others to use fear to silence what is said.