Following the Homeless Crisis to Minnesota: UC Santa Barbara’s Charmaine Chua Speaks Out

November 5, 2021

The death of George Floyd sparked gestures of unity across the world – and perhaps nowhere more than in the city where Floyd’s murder by police took place: Minneapolis. The aftermath of Floyd’s death led to ongoing protests and acts of destruction, which police ultimately countered with a curfew.

But the curfew applied to everyone, even those who didn’t have a home, creating a situation that further brought the city together as it looked to temporarily house those without a roof.

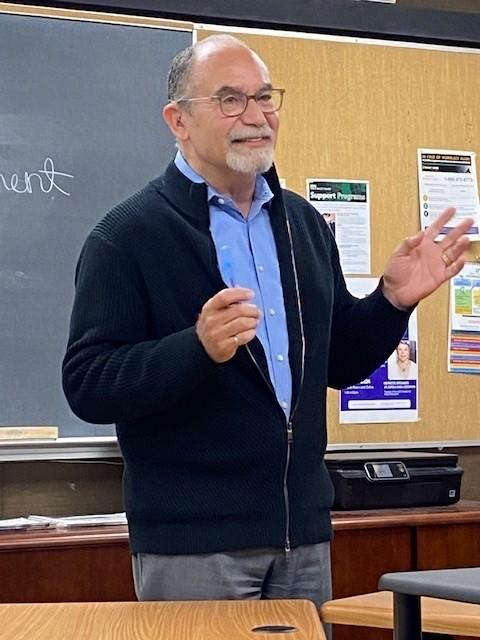

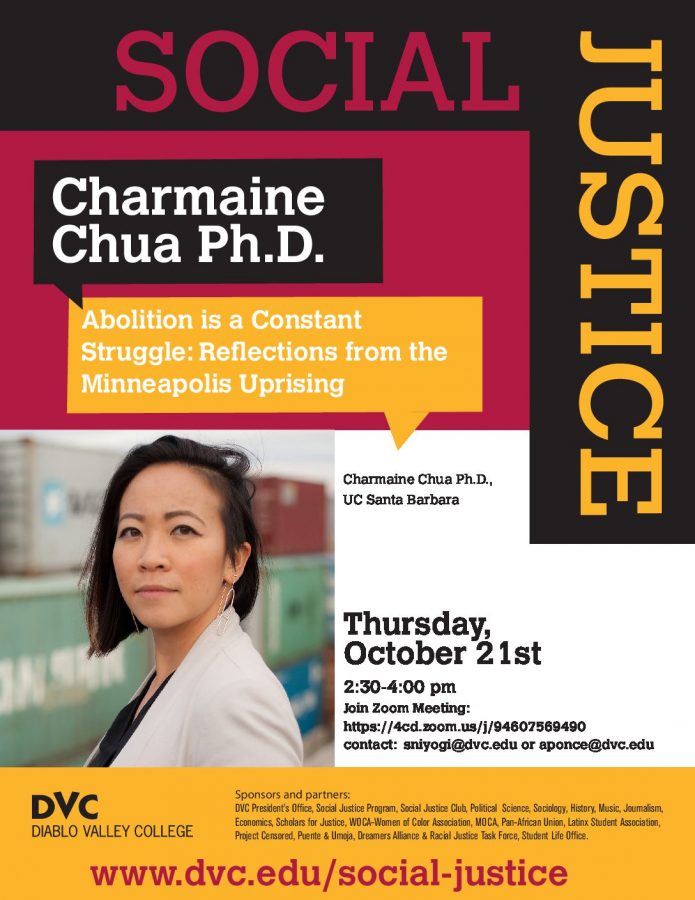

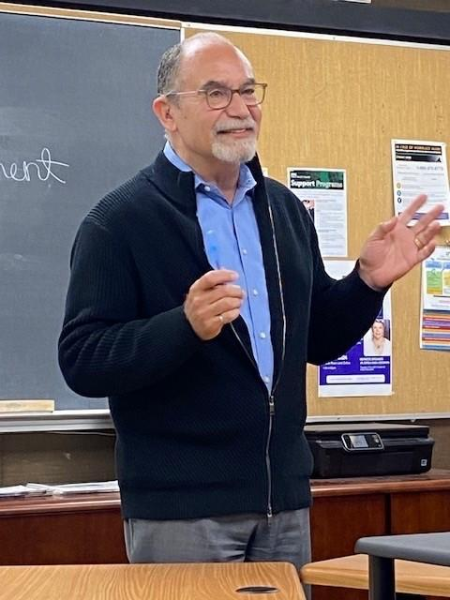

At a Social Justice Speaker Series event held at Diablo Valley College last month, entitled “Abolition is a Constant Struggle: Reflections from the Minneapolis Uprising,” Charmaine Chua, an assistant professor in the Department of Global Studies at University of California, Santa Barbara, discussed what the days were like in Minneapolis following Floyd’s murder by police.

With strict curfews in place, the homeless population was left to be either imprisoned or pushed out of its encampments, Chua said. But others came to the aid of those who needed it. In one notable example, a local Sheraton hotel became known as the “Share-a-ton” after all of its 136 rooms were rented to serve as housing for the homeless. These rooms were not rented out by the city, but instead by a pair of citizens from the city. So many unhoused people remained in the area that they created a waitlist at the hotel, and Chua recalls seeing “the most beautiful thing ever” while volunteering there.

“There were all kinds of people coming out to help,” she said. “It was high school students to soccer moms who took on the roles of being chefs, plumbers, changing the bedding.” Chua also recalled seeing people cleaning up broken glass and trash on the streets.

Chua said she also remembered seeing a change in people’s demeanor. With the increased amount of stress and chaos amid growing protests, the relief of having a home for the night defused some of the stress.

“With a safe place to stay, many unhoused people were able to heal from the trauma,” she said. “There was a wave of relief that came over everyone.”

In her talk, Chua said abolition is about “releasing the hold that the prisons and policing has on our world, both inside and outside the prison walls.” She added that people’s economic status all too often contributes to them becoming homeless or ending up behind bars.

The problem of poverty overlaps with homelessness, Chua said, which becomes an inescapable reality for many people. In an article titled “Homeless Hub,” by an unknown author, the author looks at what homelessness means to government officials.

“It has been unequivocally established that poverty and homelessness are strongly correlated, where a loss of income acts as a major factor associated with homelessness,” states the reporter. “Public opinions and government policy regarding the nature and causes of poverty tend to oscillate between two positions. Firstly, poverty is often seen as a shortcoming of individuals who will not do what is required to maintain a reasonable life. In this view, poverty is often a moral failing.”

Poverty, in the end, can become a key factor that steers people into crime, which can then lead them to jail or into homelessness.

The housing problem is not only affecting those in Minneapolis, but in communities all over. As of April 2021, there were an estimated 552,830 unhoused people in the U.S., according to “The State of Homelessness in the U.S.”

According to Chua, “Housing needs to be a solution the state demands to take on.”

The event in Minneapolis reflects how the force of police can lead to greater negative effects for those who are less fortunate. As communities continue to make efforts in creating a safer environment, Chua wants us to know that “abolition is a horizon that is constantly moving and we need to move as it shifts.”