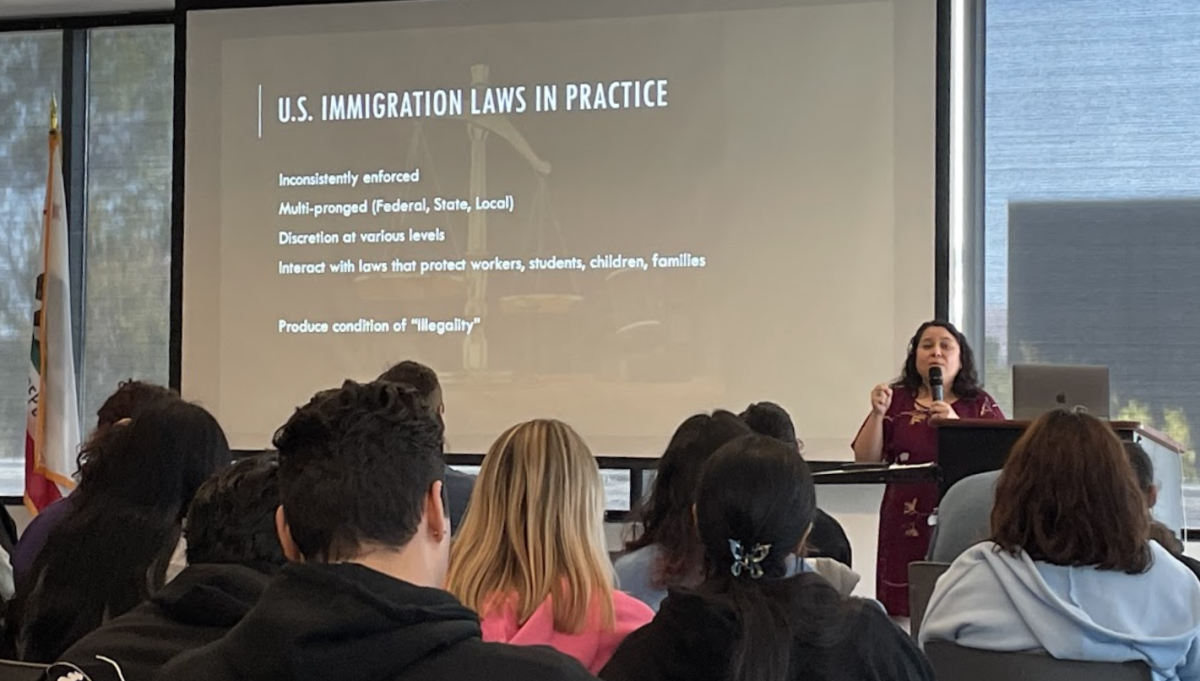

Dr. Leisy Abrego, a professor of Chicano Studies and Central American Studies at University of California, Los Angeles, delivered a lecture last month at Diablo Valley College highlighting immigration challenges for Central Americans.

The “Puente Plática” talk on Oct. 18 was part of the statewide Undocumented Student Action Week, which raised awareness about community college resources for DREAMers and UndocuAllies to foster a supportive community for undocumented students.

Abrego emigrated from El Salvador to Los Angeles in the 1980s, when she was five, and grew up in an immigrant household — an experience she said inspired her to study immigration policies.

“Immigration law in the U.S. in practice is really messy,” Abrego said, partly because “it’s very inconsistently enforced.”

Many undocumented immigrants experience difficulty navigating their rights, and often find those rights extremely limited, she said.

For example, undocumented Americans are excluded from public benefits on the federal – and often state – level even though they contribute to these programs through sales and property taxes.

Abrego said that while California offers access to in-state tuition and health care resources for undocumented college students, most states aren’t as accommodating.

Immigration policy regularly leaves the fate of undocumented immigrants to the discretion of the judiciary and law enforcement officers, who can initiate the deportation process for something as minor as a routine traffic stop, Abrego added.

Structural and symbolic violence

In this way, she said, U.S. immigration policy constitutes a form of “structural violence” in that it inhibits upward mobility and economic stability for undocumented immigrants.

“When you have people who can’t even access enough money to pay their rent and health care and bills, [who] have to stress about that every month – that, some people argue, is a form of slow death,” Abrego said.

Employment poses another major hurdle. According to United States Citizen and Immigration Services, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 established penalties for employers who knowingly hire undocumented workers.

Further, Abrego explained, a lack of public education resources in low-income neighborhoods damages young people’s college admission outlook and employment opportunities of young immigrants.

“We’re told [the educational system] is all about meritocracy, but the reality is that the system is not set up for everyone to do well,” she said.

Because not everybody realizes this, people often engage in what Dr. Abrego called “symbolic violence” toward immigrants.

“Symbolic violence is the kind of violence we all participate in,” Abrego said, “because we see the inequalities, but instead of blaming the system, we blame ourselves, we blame the people who didn’t do well.”

This deflection of responsibility often prevents people from trying to reform problematic immigration policies, and instead creates an environment where “harming people becomes not only normal, but acceptable,” according to Abrego.

History of Central American emigration

Abrego connected Central America’s history to the plight of its migrants today, highlighting the irony that “it is in large part this [U.S.] government that produces the conditions that force people to leave their country.”

During the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992), the U.S. trained and funded a military regime that, according to a United Nations report, displaced about a quarter of the nation’s population.

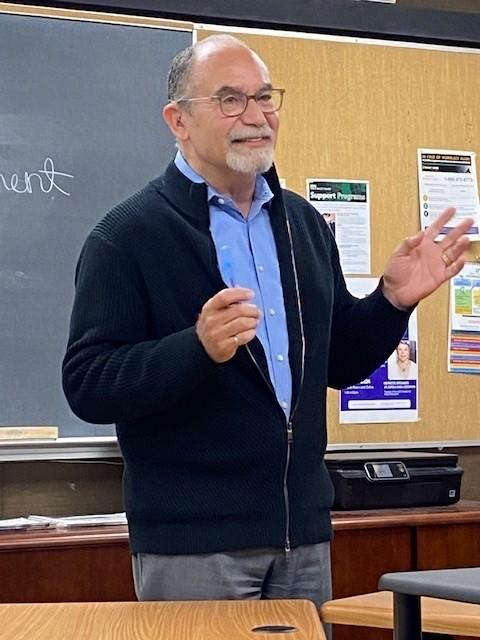

The event’s second guest speaker, Dr. Raúl Moreno Campos, who likewise immigrated to the U.S. from El Salvador as a child, and currently teaches Chicano Studies at CSU Channel Islands, elaborated on this point.

“The Salvadoran Civil War and its legacy… are both products of 100 years of U.S. intervention in Central America,” said Campos, “and the principal reason for why Salvadorians like… members of my family and myself came to the United States.”

In the 1980s, the U.S. government denied citizenship status to Central American immigrants even though international law protected their right to apply for asylum and refugee status, Abrego said.

As a result, about half of the 4 million Central American immigrants currently residing in the U.S. are undocumented or have only temporary protected status.

Additionally, the U.S. deepened the economic instability in Central American nations and spurred further waves of emigration with policies like the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), signed in 2004, which enabled U.S. multinational corporations to exploit the under-regulated Central American labor markets.

An era of detention centers

In 2014, tensions reached new heights as the Obama administration increased the number of detention centers 35 times in a span of six months, making them the fastest growing sector of the U.S. prison-industrial complex.

When images of undocumented Latin American children living within the poor conditions of U.S. immigrant detention centers flooded the news that year, President Obama channeled government funds into Mexico’s police and migration authorities, in order to strengthen America’s border security without drawing unwanted attention to the abusive activity of the U.S. Border Patrol.

As Abrego put it, Obama “decided to expand the U.S. border into Mexico, in a sense.”

As a result, the number of Central American adults detained in Mexico doubled within three years, and the number of detained children increased tenfold.

Abrego shared photographs of “family residential centers” that were effectively prison cells repurposed for the detention of undocumented immigrants.

“[Immigration officials] were treating people like inmates for an international human right… to seek a place of safety,” said Abrego.

In the press, Obama followed former President Ronald Reagan’s lead by associating Central American migrants with “crisis.” Yet all the while, immigration detention centers perpetuated a crisis of their own, according to Abrego.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the University of Chicago compiled 30,000 pages of reports detailing cases of abuse, extreme fear tactics, and sexual assault that detention center authorities inflicted upon minors during the Obama administration, she said.

And during the Trump administration, the conditions at detention centers only worsened. In 2018, former President Trump implemented a zero-tolerance border policy that legalized the separation of migrant families.

Under this policy, “every adult, even if they legally had the right to apply for asylum, was processed through ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], and parents were separated from children in at least 2,700 cases,” Abrego said.

She added, “There was never any centralized system to keep track of people to help them find each other after this process,” thereby delaying family reunification, sometimes for a matter of years.

Abrego said Trump scapegoated Central American immigrants for gang-related crime and dehumanized them in his speeches and social media posts to emotionally alienate immigrants.

The Trump administration not only exposed deep-seated xenophobic sentiments in the United States, but also “fueled hate across borders,” which has had lasting impacts, Abrego said.

“Mexicans then also started repeating the same kinds of things that Trump supporters here would say against immigrants.”

“[Trump] couldn’t even say, ‘undocumented children,’” Abrego said. “His phrase was always, ‘illegal unaccompanied alien minors.’”

But, as Abrego demonstrated, “there is nothing inherent in a human being that makes them undocumented or ‘illegal.’”