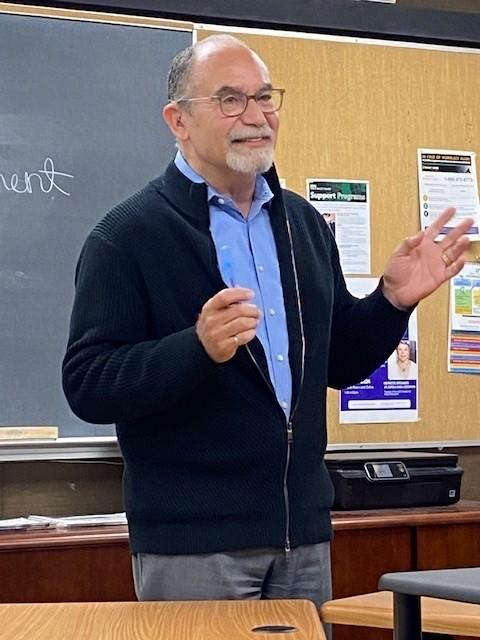

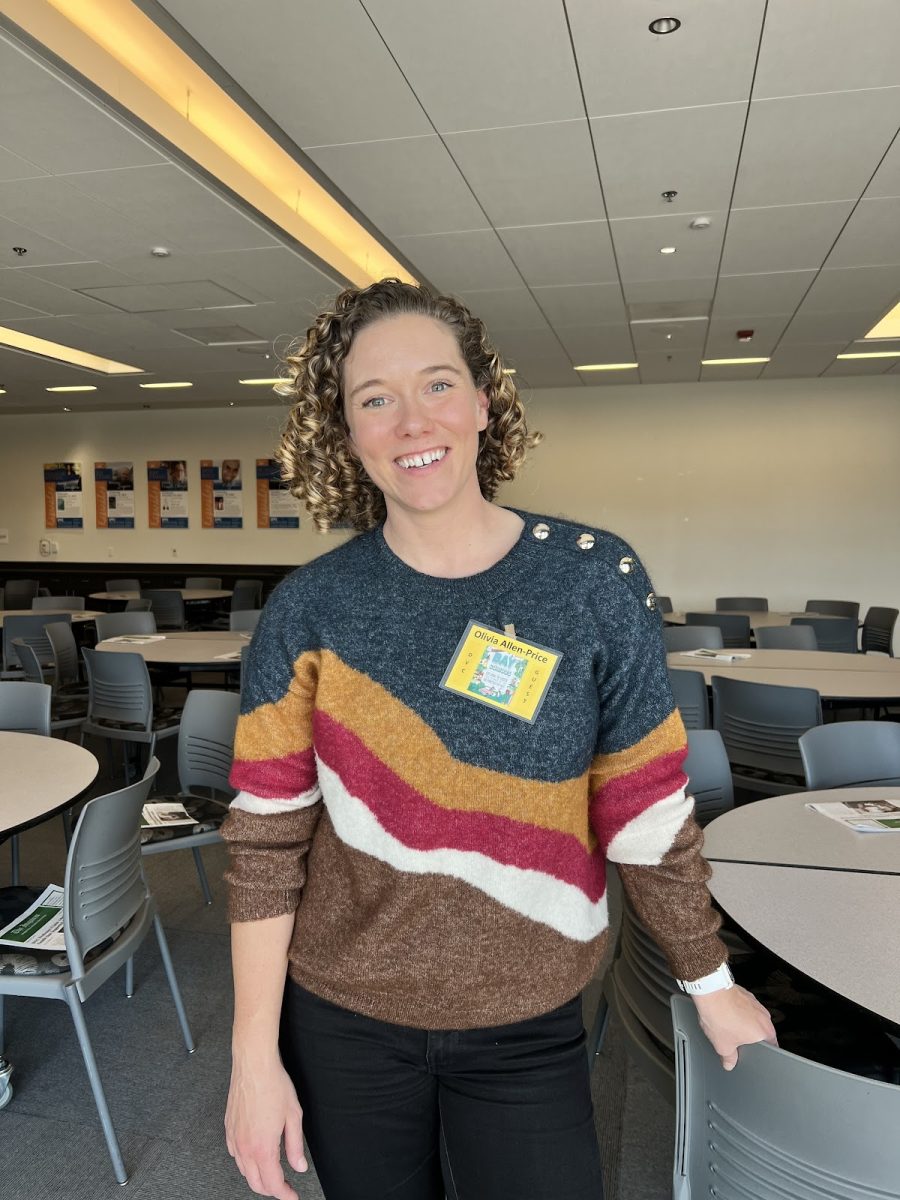

In honor of Women’s History Month, KQED journalist and “Bay Curious” podcast host Olivia Allen-Price visited Diablo Valley College on March 7 to discuss a group of women who greatly influenced the Bay Area through their impacts on civil rights, art and environmentalism.

Students gathered in the Diablo Room to listen to Allen-Price’s interesting anecdotes that included pioneers like Mary Ellen Pleasant and Frida Kahlo as well as activists like Sylvia Mclaughlin, Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

The mysterious and alluring Mary Ellen Pleasant, also known as “The Queen of Civil Rights in California,” was a complicated figure, Allen-Price explained, because “she wrote three autobiographies about herself and they each contradicted each other.”

Although Pleasant was believed to have grown up in slavery as a white passing woman, she was able to have an advantage “to kind of walk between the black community and help people escape slavery,” said Allen-Price.

After marrying into wealth and becoming a widow at a young age, Pleasant boarded a ship to San Francisco. Shortly after, she noticed that during the Gold Rush, single men in search of gold were also in need of a place to stay and wash their clothes. So she opened multiple high-end boarding houses catering to wealthy businessmen and politicians.

“She worked in the boarding houses. She got to know the people who were living there because she knew that these were the men who ran the town,” Allen-Price explained. Through these connections, Pleasant was “ultimately trying to bring the Underground Railroad out west so there could be more safe places for black people to live.”

“She’s kind of had almost two identities to different groups of people within the city,” said Allen-Price. “But her secret wouldn’t stay a secret for very long.”

After being asked to get off a streetcar in San Francisco because she was identified as black, Pleasant took the operator and the company to court in a case that made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that streetcar exclusion based on race was unlawful.

The story of Pleasant’s life was eye-opening to many students who attended the talk.

“I think it was really inspiring that she’s kept her identity a mystery, with her three autobiographies, and then really emphasized the focus of her career on helping with civil rights,” said DVC student Koko Taylor.

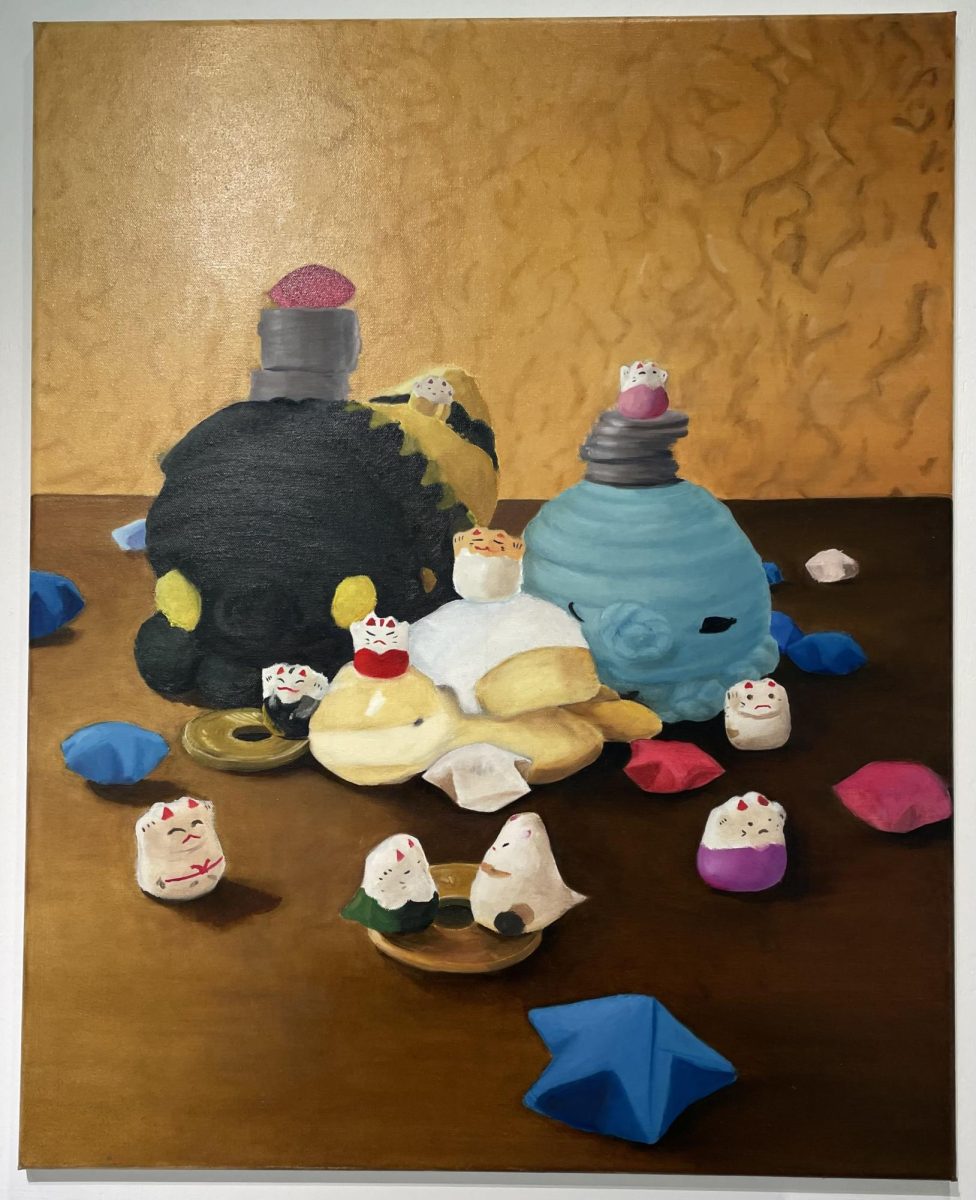

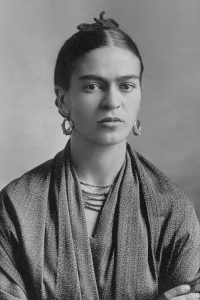

Frida Kahlo

In her presentation about the life of Frida Kahlo, Allen-Price zeroed in on the artist’s specific influence in San Francisco. Kahlo came to the city in 1940 with her husband, the world famous painter Diego Rivera, who was commissioned to paint murals. Since she wasn’t as busy as her husband, she would meet up with fellow artists.

“She would get together with Haley Pele De Lappe and Lucille Blanche to make art together,” Allen-Price said.

“They were definitely pushing the boundaries in what they were drawing to experiment with this kind of more edgy art for the time.”

Following an accident she experienced at 18 while riding on a streetcar that collided with a bus, Kahlo suffered great pain all her life. Allen-Price said it was speculated that Kahlo wore traditional Mexican clothing to aid her in comfortability and mobility. And in San Francisco, people were interested in her unique outfits.

“They are really impressed by all the dresses and rebozos I brought with me and the painters want me to model for their portraits,” Kahlo wrote in a letter to her mother, according to Allen-Price.

In addition, Allen-Price mentioned that during her stay in the city, Kahlo and Rivera made friends with her surgeon, a man named Dr. Elloessor, who brought them on trips around the Bay Area. “One of those trips would end up being pretty important for her art,” said Allen-Price. “They went to the garden of Luther Burbank in Santa Rosa.”

The garden was known for its hybridized plants, and Frida was able to take inspiration from those elements to incorporate into her own art. “She was really fascinated by the idea of hybrid bodies. The idea of sort of organic textures and things reaching into the ground starts to show up in her art almost immediately,” said Allen-Price.

When she came back a second time to San Francisco, Kahlo was more established as an artist and people flocked to see her work. “Her art also gets displayed at the World’s Fair on Treasure Island, which was a huge event that drew half a million people to it over the course of the month that it was open,” added Allen-Price.

“It’s also shown at the Legion of Honor, and it falls into the hands of a really influential collector who’s involved with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.”

Kahlo and Rivera’s presence in the Bay Area was also significant in the evolution of Latin American identity and empowerment.

“At the time that [Kahlo and Rivera] came, Latinos were really fighting for still a quality representation, especially in the art world,” Allen-Price said. “Frida and Diego were kind of like a blueprint for that—and not just how you could be taken seriously as an artist, but also how you could be an activist at the same time.”

Students who attended the talk likewise found the descriptions of Kahlo’s life in the Bay Area fascinating.

“I liked how she talked about Frida Kahlo’s presence in San Francisco because she really became a common name there,” said DVC student Anabel Lopez.

“She inspired and set an example of Latino people being taken seriously in the art industry and demonstrating activism in her art at the same time.”

Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick

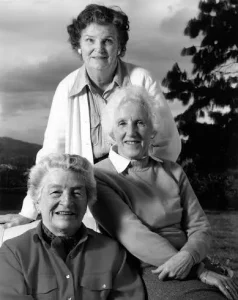

Lastly, Allen-Price talked about a group of three women, Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick, who founded the nonprofit Save the Bay in the 1960s and left a lasting environmental impact on the Bay Area during a period when its land was becoming more valuable—and also more polluted.

“Back in the day, it was mostly privately owned. So there was sort of endless potential for a lot of these towns that touched the bay, or businesses that had coastal properties, to expand as much as they wanted. There were no rules against it,” said Allen-Price.

She explained the detrimental effects of crowding the bay with more development, which destroyed wildlife and natural habitats.

For DVC professor Melissa Jacobson, who teaches California and women’s history, the stories about the women’s early environmentalism were illuminating.

“I mean, it just makes my life worth living, to go out into nature and beyond the water and to think and see all the animals and birds,” said Jacobson, who organized Allen-Price’s presentation, and uses the book adaptation from the podcast to teach her own California history class.

“I think [about] all that would be gone, without these three women who just said it doesn’t have to be this way,” she said.

The stories of the three environmental women are little known to most people in the area, Allen-Price said, despite their incredible qualifications and backgrounds.

“These women are kind of oftentimes billed as housewives, but they were very highly educated. Gulick was a major in economics at UC Berkeley, Kerr had a political science degree from Stanford, and McLaughlin was a graduate of Vassar,” she said.

“They were the wives of UC Board of Regents members. So they were very well-connected, relatively wealthy, well-educated women.”

Allen-Price told the story of one night when the women invited different environmental groups and activists to a dinner. They wanted to put out a call for action, but unfortunately it didn’t go well because all of the organizations were committed to other problems.

“By the end of the night, it kind of becomes clear to them, ‘It needs to be us, we have to do something if we want anything done at all.’ So that night Save the Bay was founded,” she said.

From there, the women went to work. They talked with experts, scientists and ecologists. They started a newsletter charging $1 a year, and with that money they were able to print fliers and hand them out to yachters on opening day at the Berkeley Marina. Their argument, Allen-Price said, was, “if you like your fancy yachts, and want to keep doing this, you need to help save the bay.”

This activism was also advantageous to them because of the influential people they were able to meet. “So they kind of got people who were well connected, who had money and power, working with them, through some pretty strategic information sessions,” she said.

In the early 1960s, the women decided they needed to take the issue to a statewide level, so they persuaded politicians to establish the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission. According to Allen-Price, “ Their job was to stand between environmentalists and environmental needs—[to] basically kind of broker what can get developed [and] what is in the interest of the general public.”

Though all three women have since passed away, Save The Bay remains an active organization focused on issues such as re-establishing wetlands and preservation of wildlife, said Allen-Price.

The stories and inspiration people can still draw from their accomplishments lives on as well.

“If you are a woman, reading about amazing things that other women have done is inspiring. It can make you feel like anything is possible,” said Allen-Price.

“There are so many fascinating figures in history who have done so many things, from going to space to being on the forefront of the Civil Rights movement. So no matter what your passion is, there’s somebody in history who’s probably done something that you can look up to.”