Jury Says: ‘Not Guilty’

September 10, 2008

Erick Martinez sat with his head in his hands, crying as the court clerk read the jury’s verdicts on each of nine felony counts of computer fraud.

At his side, Deputy Public Defender Karen Moghtader began to grin as the first not- guilty verdicts came rolling in. As the fifth count was announced, she turned to smile at Martinez’s sole supporter in gallery, his housemate and business partner.This friend, sat stiffly behind Martinez, a book pressed against his mouth, until the ninth and final not-guilty verdict was read. Punching his fist in the air, he said loudly, “Yeah, I knew it!”

Prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Dodie Katague, stared straight ahead, his face expressionless. He quickly left the courthouse when the proceedings ended.After a three-week trial and more than a day of jury deliberations, former DVC student Martinez, 35, was acquitted Sept. 5 on all charges that he changed 15 of his own grades, as well as those of some friends, while he was a student worker in DVC’s admissions and records office.Later, he would tell an Inquirer reporter, “I told you from the beginning I was innocent. It’s done, it’s over, it’s great.” If convicted, Martinez could have faced more than eight years in jail and deportation to his native Guatemala, even though he is a legal resident. One of 54 former students accused in a cash-for-grades scandal that rocked the college and put DVC at the center of national and international media coverage, Martinez was the first to put his fate in the hands of a jury. At the conclusion of Martinez’s trial, juror Rosella Kerr of Antioch said DVC’s admissions and records office was in such disarray there wasn’t sufficient evidence to prove who had made the grade changes on his and his friends’ transcripts.

“Everything at the college was in such chaos,” Kerr said. While on the stand, Martinez testified about lax security in the admissions and records office during his time there. He said time cards were inaccurate and mostly fabricated, passwords were shared with new employees, and workers often left their stations for breaks and even class without logging off their computers.

At the outset of his cross-examination, Katague raised the issue of Martinez’ sexual orientation. Why, he asked, had Martinez come to the United States from Guatemala in 1997 at the age of 24. “I wanted to live in a place that I didn’t have to lead a double life,” Martinez answered. “You received political asylum because you were gay?” “Yes” “Have you ever lived in the Midwest?”

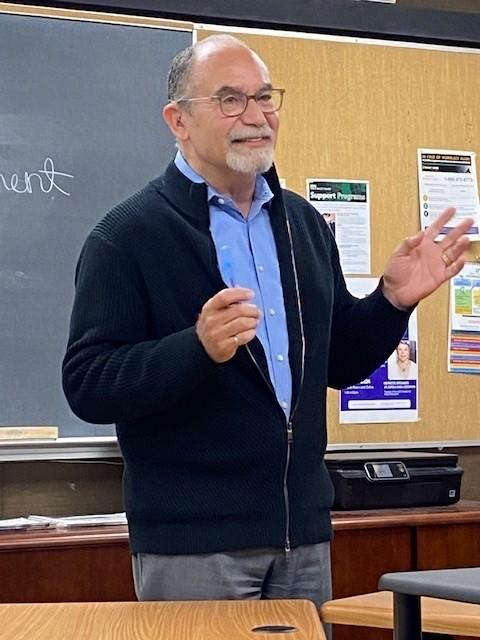

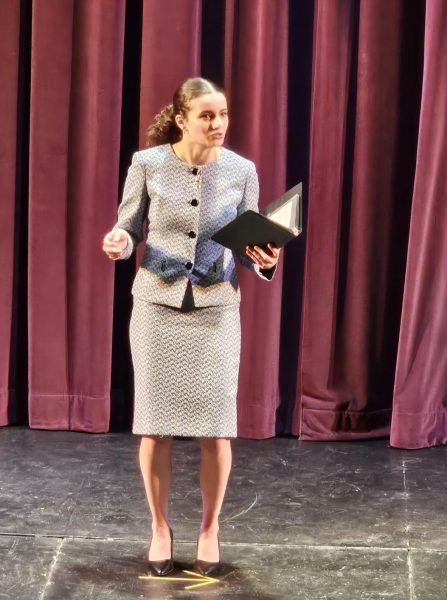

The jurors noticeably flinched at the antagonistic tone of the prosecutor’s question. Moghtader later told the Inquirer that Martinez was granted asylum on humanitarian grounds after having almost died after being beaten up by police in Guatemala. “It was inappropriate,” she said of Katague’s line of questioning. “I don’t think sexual orientation had much to do with the trial.” During the prosecution’s closing statements, Katague argued that Martinez was the only person who had motive and opportunity and who also benefited from 15 A’s being added to his transcript. “Common sense tells you that the defendant was the one who changed his grades,” Katague told the jury. Moghtader, however, emphasized it was not the defense’s job to show proof of who could have changed Martinez’s grades. To find him guilty, she told jurors, they would have to “believe he was lying when he said he didn’t do it.” “You,” she said, “are the sole judges of his believability.” Moghtader closed by using a color-coded chart to emphasize the jury’s obligation to find Martinez guilty only if they believed that he committed the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. In an interview with the Inquirer during the trial, Katague said Martinez’s case was completely separate from the grades-for-cash scheme in which more than 400 grades were sold for thousands of dollars between 2000 and 2006.

The three ringleaders of that scandal – Julian Revilleza, Jeremy Tato, and Liberato “Rocky” Servo – all pleaded guilty and agreed to help prosecutors in exchange for lighter sentences.

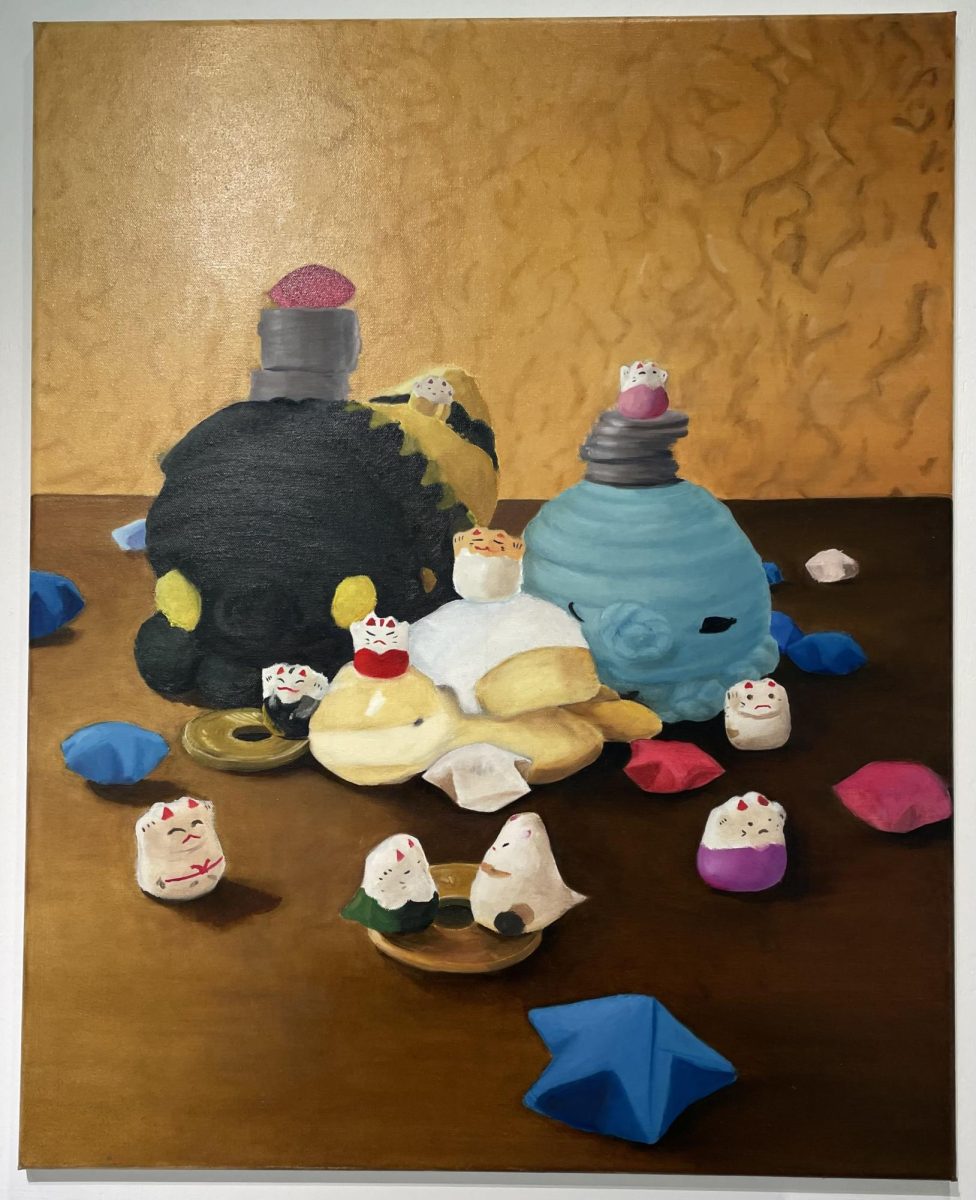

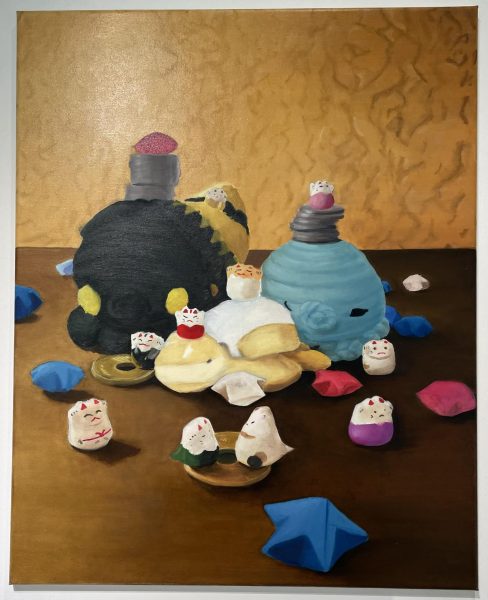

Martinez, who was first questioned in February 2006, was also offered a plea deal, but turned it down. Only Revilleza testified at the Martinez trial. Katague contended that Martinez changed his own grades and those of his friends in order to improve his transcript and theirs, but never accepted money. When speaking with reporters outside the courtroom, Martinez said he has no plans to pursue higher education, that for now he wants to concentrate on running his international fusion home décor shop in Benicia. Moghtader said her client feels “his reputation was really tarnished,” and hopes that this verdict “will undo some of the damage.”