Numbers reflect harsh reality for DVC students of color

December 2, 2015

A disparity in student success rates between racial groups at Diablo Valley College has persisted for over a decade; faculty and administration have only begun to take data-driven steps to address it in the past year.

DVC has the 7th largest achievement gap in the state, according to a recent report by the Student Equity Committee.

Latino and black students struggle to pass their classes and transfer while Asian/Pacific Islanders, white, and international students succeed in those areas, according to comprehensive studies performed by the Contra Costa Community College District.

Black students are underrepresented in transfer preparedness relative to the student body. According to a District Office of Research and Planning report, black students — who accounted for 6 percent of the student body from 2003 to 2009 — represented only 3 percent of transfer-prepared students.

In recent years, that deficit has only widened. Black students made up just 2 percent of all of DVC’s transfer-prepared students from 2009-2012.

DORP defines transfer preparedness as “the percentage of first time students with a minimum of 6 units earned who attempted any Math or English in the first three years, and completed a minimum of sixty transferable units with a minimum GPA of 2.0 within six years of entry.”

Asian/Pacific Islanders, Filipino and international students were all slightly overrepresented in transfer preparedness. Accounting for 14 percent, 5 percent and 13 percent of the student population respectively, they represent 16 percent, 7 percent and 18 percent of all transfer prepared students.

When looking at transfers to the UC and CSU system, the same report demonstrates that Asian/Pacific Islander students are also overrepresented, accounting for 21 percent of all transfers compared to their 14 percent share of the student body.

These trends are also apparent in course success rates — defined as receiving a passing grade in the course. Black and Latino students pass their classes at much lower rates. In 2015, the CCCCD Center for District Research reported that across all disciplines, the success rates of black and Hispanic students significantly lag behind those of Asian/Pacific Islander and white students, with rates of 58.16 percent and 67.00 percent versus 73.17 percent and 74.14 percent respectively.

The gap is even wider when measuring success rates in basic skill courses such as math and English. From 2009 to 2014, the average success rates of each demographic were:

- Asian/Pacific Islander Students: 66.8 percent

- White Students: 66.0 percent

- Hispanic Students: 58.7 percent

- Black Students: 46.5 percent

Furthermore, the success rate of black students in basic skill courses reached 34 percent in 2013; 23 percent lower than the lowest performance of any other demographic throughout the six year period.

Dr. Mark Akiyama, chair member of the Student Equity Committee of DVC said, “the trends that you see are representative of not only an institution problem, but a system problem.”

Andrew Barlow, professor of Sociology at DVC, confirmed and expanded on Akiyama’s point: “it’s not just DVC, but even worse it’s the whole public school experience from K-12 as well. A very high proportion of our students, 70 percent, come to us without the English and math skills they need for college level work”. From this perspective, the “achievement gap” would more accurately be described as an “opportunity gap”; focusing exclusively on the end result of “achievement” does not sufficiently encompass the scope of the issue.

Student equity programs have only been funded by the state since 2014, when their inception was mandated by the state back in 1996. As a result the first two equity plans, written in 1996 and 2006, were both shelved and left unread. Even with federal funding, from the time the institution receives the funds — approximately $700,000 dollars in 2014 and $1.4 million in 2015 — it has only three weeks to submit a detailed, specific proposal outlining targeted improvements in student equity, not success. Meaning, if every group in the school improves, but a gap between demographics still exists, it has failed the state’s standards for allocation of funds.

With regards to the achievement gap in the classroom, the question of developing specific fixes is a complex one. Not only do different disciplines necessitate their own approach to equity, but the individual teaching styles and practices of the professors within those disciplines create an almost immeasurable amount of variation between courses.

This problem has historically been exacerbated by the fact — as noted by Akiyama — that until very recently “DVC has not been a ‘data driven’ institution. In other words, decisions were not made based on data, but based upon other ‘factors’. What those factors were, I couldn’t tell you.” As a consequence, DVC’s previous attempts to close the achievement gap have been largely ineffective.

With the data from the recent reports, the Student Equity Committee has developed new solutions to attempt to promote student equity, which sociology professor and Student Equity Plan co-writer Sangha Niyogi notes “…entails a change in the mindset of everyone involved…to see how different students bring different strengths to the classroom, and not necessarily identify these students as ‘students’ with problems…. We’re investing a lot in professional development and student services so we can meet the students where they are.”

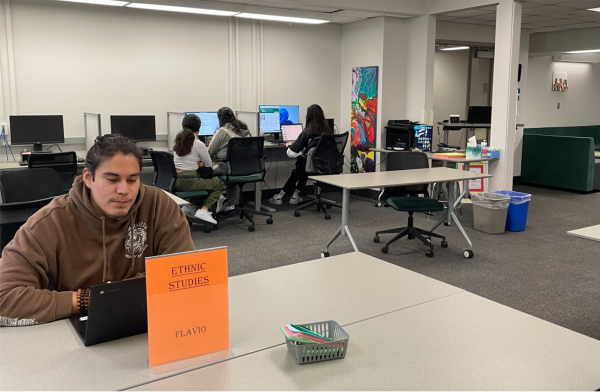

“Cohort programs,” such as those run by Umoja and Puente clubs, aim to bridge the gap by fostering the growth of supportive communities for “at risk” demographics by leading a group of students through the same path of courses.

Another proposed solution is the development of a First Year Experience, or FYE, program. This would create a more focused and guided college experience, cutting down on “wasted credits” that do not actively help students move towards accomplishing their goals.