Fighting to survive from Honduras to the US: The story of Soledad Castillo

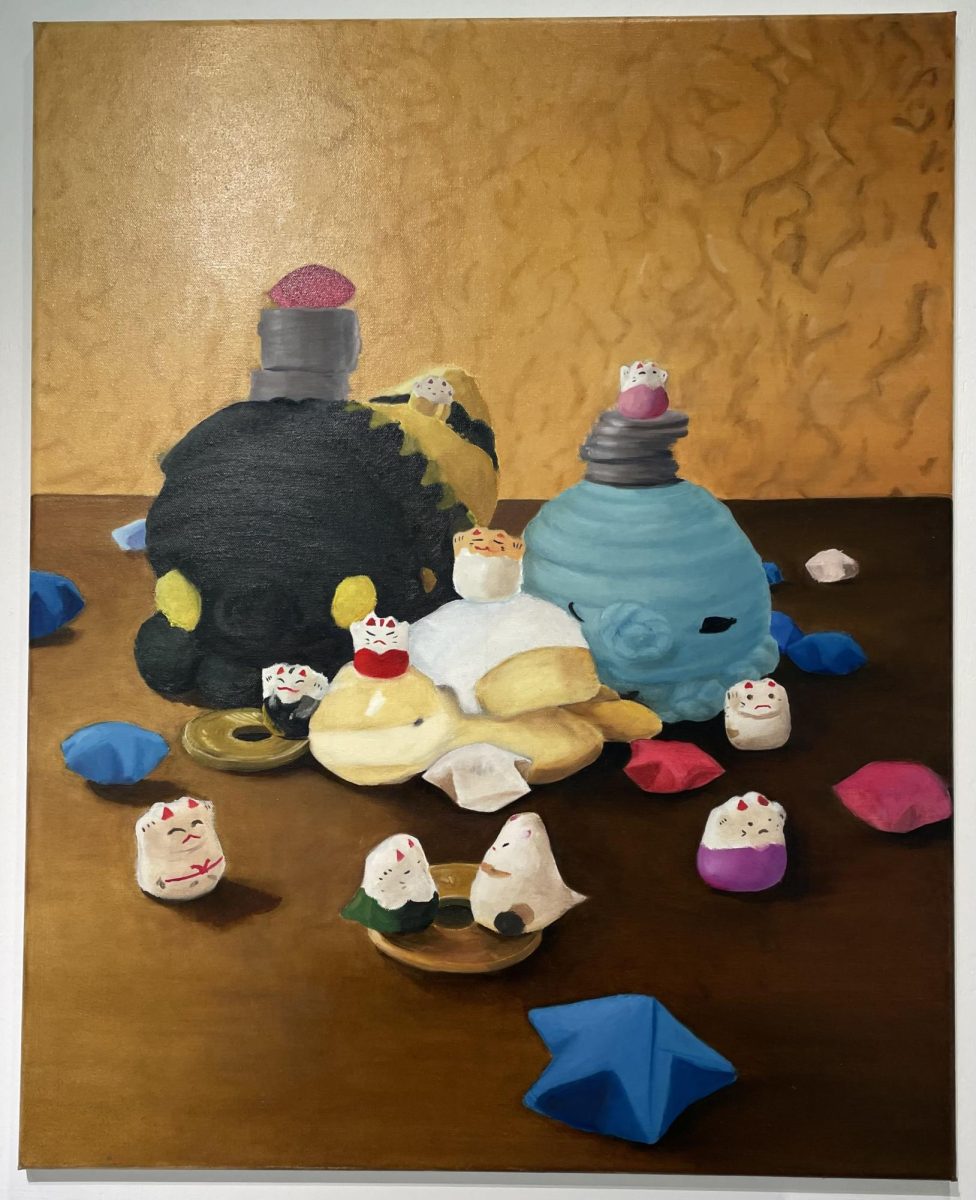

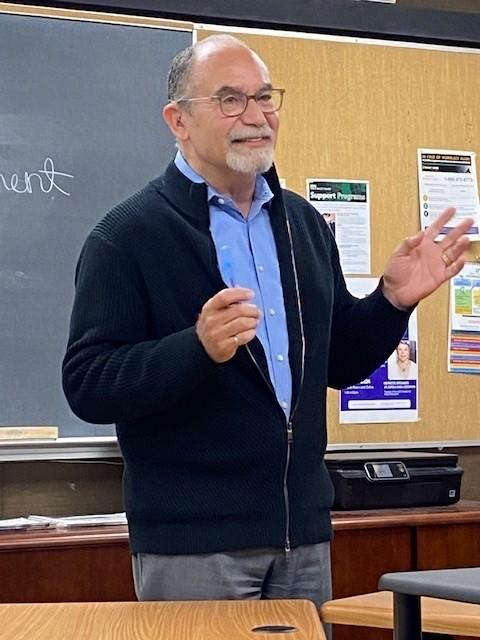

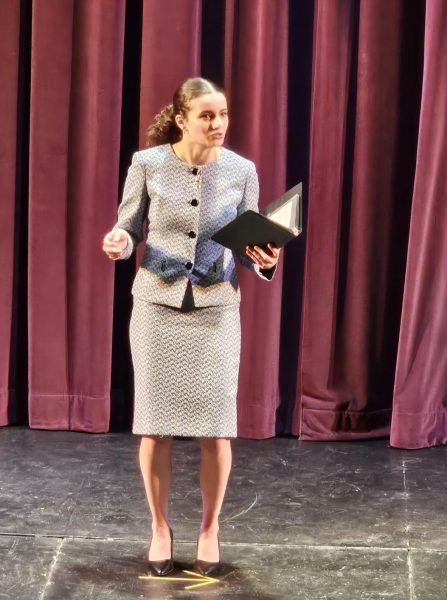

Soledad Castillo (center) tells her story about making it to the United States alongside Stephen Mayers (left) and Jonathan Freedman (right) in the Diablo Room on Sept. 25. (Emma Hall/The Inquirer).

September 30, 2019

A 14-year-old girl from Honduras lay in a van with complete strangers venturing through Mexico. They were all refugees migrating to the United States in hopes of a better life. The Coyotes – people who smuggle immigrants – transported the girl, her family, and the other refugees, placing cardboard over them so la migra (immigration police) wouldn’t see them.

The next day everyone in the van trekked along Mexico’s scorched desert to reach a ranch house where they believed they would stay overnight. With only a liter of water and a can of beans per person, they continued their journey. The Honduras girl’s feet were covered in blisters.

“You don’t think about how hard it is to cross. You think about survival—that you want a better future,” the girl said.

She struggles to recall what exactly happened when they reached the ranch house. But she does remember being covered in cactus pines while hiding from la migra, the strangers she laid with not making it, and the coyotes leaving an Asian girl to die.

The girl also remembers being robbed by gang members while still in Mexico. She remembers her family not having enough money to make the rest of their trip. She remembers being raped by those same gang members. She remembers their hands violating her body. She remembers not being able to speak.

Now, she is speaking up.

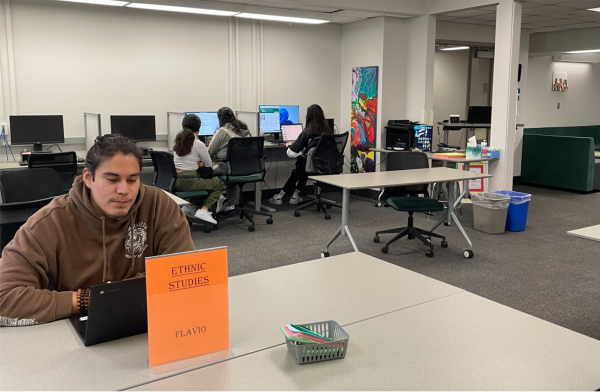

The girl’s name is Soledad Castillo and she told her story to a packed audience in the Diablo Room at Diablo Valley College on Sept. 25. The event was hosted as part of the Equity Speaker series to promote, “Solito, Solita”, a collection of stories about young refugees, including Castillo, migrating from Central America.

“I use my story to inspire others instead of feeling sorry for myself,” said Castillo. “I’ve learned to love myself despite all that has happened to me.”

When Castillo arrived in the U.S., she did not speak English. Her father was sent back to Honduras and Castillo, at 16, was thrown into foster care. In the presence of an abusive foster family, Castillo felt alone, forced to live in a country unfamiliar to her.

Despite her hardships, she was determined to fight for the life she had dreamt of. A friend from school who knew English spoke to her social worker about the abuse and Castillo was later placed in a new foster home where she was cared for. Castillo now works in foster care, making sure children who only speak Spanish are given the proper treatment they deserve.

Castillo would find the platform to share her story after meeting English professor Steven Mayers at San Francisco City College. When they met, Castillo told Mayers about her journey and life as a refugee in the United States.

“I am focusing on the structural forces that force people to make decisions to relocate,” said DVC political science professor Albert Ponce, who moderated the event. “Soledad mentioned, ‘I didn’t choose to come here.’ We didn’t all make those choices. Some choices were dependent on our own survival.”

Castillo learned how to survive at an early age. While living in Honduras, she was sexually abused by her stepfather. When she mentioned the abuse, her mother didn’t believe her. Castillo was also misdiagnosed with lupus, which nearly cost her her leg. She was forced to work as a housekeeper at 11 after the death of her grandmother in order to keep food on the table. Castillo’s dinners consisted of a tortilla and salt. She also lived in the midst of gang violence and extreme poverty.

According to the Council of Foreign Relations, Honduras is one of the most violent and dangerous countries in the world to live in, along with other Central American countries like El Salvador and Guatemala. Honduras has a homicide rate of 59 per 100,000 people, with 5,154 registered homicides by the end of 2016, the latest figures available.

InSight Crime finds that 80 percent of homicides involve gun violence, which is double the global average. Regarding poverty, the World Bank Group found 66 percent of the population living in poverty in 2016 and one out of five Hondurans living in extreme poverty.

“I saw it with my own eyes how hard it is to live there. I understand why there are a lot of people who are trying to leave,” she said. “It’s not a choice, it’s not easy to leave your family behind. Leaving my sister and my brothers, it wasn’t easy, but what other option do we have?”

Survival for Castillo meant risking her life to come to the U.S., an obstacle that many refugees must face. Mayers and Jonathan Freedmen, both editors of “Solito, Solita” and experts on Central American refugees gave their insights during the event. Both have worked with several other refugees besides Castillo while assembling the collection and believe the book is more relevant than ever. President Donald Trump’s strict citizenship policy has created an anti-immigration rhetoric while promoting a wall between the U.S.-Mexico border and openly referring to Central American refugees as “rapists” and “murderers.” When they both attended a bi-national conference to finish “Solito, Solita”, the professors visited Tijuana. During this time, Trump claimed there was a caravan invading the U.S. However, what Mayers and Freedmen witnessed was far from it.

“Having covered the border since the 1980s I’ll say this: there was no invasion,” said Mayers. “We actually went to the fence between Mexico and the United States, and you know what we saw? We saw nobody.”

Castillo is now using her story of survival to inspire and to inform others about the challenges of migrating to the U.S.

“It was a difficult journey but I’m here today and all that I went through in the past is a part of the person I am today,” she said. “For those who went through the same, I want to tell you that anything is possible.”

Jonathan Freedman • Sep 30, 2019 at 7:06 pm

Great story, Emma Hall. You captured the essence of Soledad’s experience, conveyed the emotional impact and put it in the larger context of poverty & violence in Honduras, as well as the injustices against people like Soledad Crossing the US border.

You have the makings of a journalist!

Jonathan Freedman