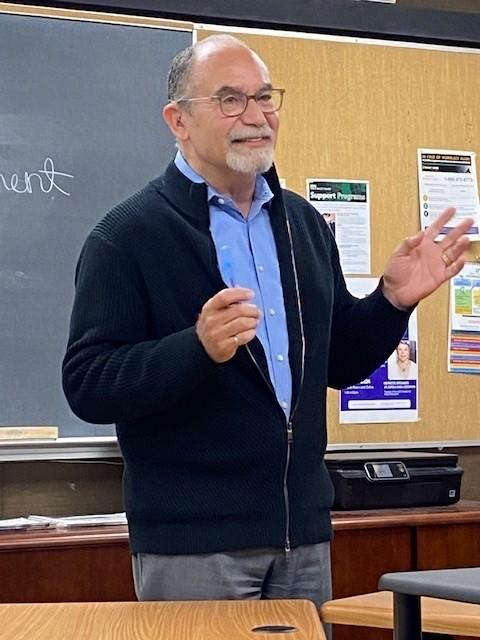

Crime Reporting is About Gritty Details, and Nate Gartrell is a Gritty Reporter

Nate Gartrell

March 24, 2021

In the summer of 2007, journalist Chauncey Bailey was murdered on the streets of Oakland for investigating a local crime syndicate and the finances of Your Black Muslim Bakery. At the time of the trial, Nate Gartrell was a green reporter assigned to cover this bloody case.

“Sitting in court and seeing pictures of this dude riddled with bullets was pretty striking,” Gartrell said. “It kind of served as my intro to journalism. [It was some] pretty horrific sh*t, seeing the results of a journalist getting assassinated.”

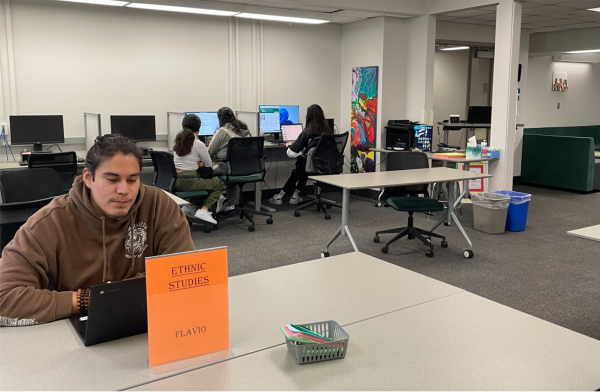

Now 31, Gartrell is the East Bay Times’ crime and courts reporter. Sharing this story over Zoom with Diablo Valley College’s journalism department on March 16, Gartrell gave his takes on journalism and why he’s still a reporter.

Gartrell said his interest in investigating crime goes back to his childhood in Benicia, California, a small town near Vallejo. Growing up, Gartrell saw crime all around him, most notably, a serial killer who at the time was kidnapping kids. “It’s hard to avoid when you walk down the street and there are missing posters everywhere,” he said.

Similarly, Gartrell described how crime can often be hiding in plain sight in the bedroom communities of the East Bay. At one point, police had raided a cartel house in Benicia filled with Uzis and cocaine, he said. Gartrell was surprised to learn the Sinaloa Cartel had an operation in his small, quiet hometown.

“There’s all kinds of organized crime organizations right here in the area,” he said. “People who seem to have an air of legitimacy are operating multimillion-dollar illegal businesses out in the open.”

Since he started covering the crime and courts beat for the East Bay Times, Gartrell has developed a routine that helps him track down some of the most interesting stories. Scanning local court calendars, he searches for detention and trial hearings on a daily basis. And while visiting county courthouses once a week, he looks through public records to find “all the juicy sh*t.”

But the emotional burden of seeing and writing about gruesome crimes takes a toll, he said.

“You definitely do get a little desensitized. People can get really numb, outwardly showing little empathy. It can slowly eat at you.”

He added, “Journalists are alcoholics and use tons of drugs, and it’s probably not a coincidence.”

Reflecting on how the pandemic has affected journalists’ work, Gartrell said it is actually now easier for court reporters to cover multiple jurisdictions because most trials are either live streamed or recorded.

Yet surprisingly, according to Gartrell, this has not resulted in better news coverage. “There’s less and less people watch-dogging public government as newspaper staffs get smaller and smaller,” he said. As a result, “one person just gets a bigger and bigger area and more stuff gets thrown to the wayside.”

To his point, Gartrell wrote almost 700 articles between 2020 and 2021, demonstrating the sheer workload placed on reporters during the age of shrinking newsrooms.

Still, Gartrell said he enjoys the fast pace of court reporting.

“You get to cover different things every day, you get a front row seat to all this interesting stuff that happens. It’s hard to get bored in this profession,” he said.

Offering advice to DVC’s aspiring journalists, Gartrell said that young journalists should get familiar with the public records system. “It’s ridiculously easy,” he said. Many reporters don’t know how to submit Public Records Act forms, so learning how to use those resources works to their advantage.

When maintaining sources such as police, district attorneys, public officials and defendants, he offered a simple piece of advice: “Remember you’re gonna do stories that piss them off here and there.”

For example, last year a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, a white supremacist gang, released a video from prison refuting a story Gartrell had written.

Gartrell said he tries not to worry about the possible violent repercussions of his reporting. “They’re pretty sophisticated organizations, they don’t shoot from the hip that way. I don’t think the Sinaloa Cartel would kill an American journalist,” he added.

For Gartrell, journalism is about bringing gritty, difficult stories to light. “If you’re doing good journalism, you’re going to anger people,” he said, “unless you want to write about bake sales.”