New Study Shows California’s Water Usage Is Contributing to Rise of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

October 6, 2021

Bay Area environmental research groups Pacific Institute and Next 10 paired up in a webinar on Sept. 28 to discuss a new study focused on water usage, sourcing and the ways that both are impacting greenhouse gas emissions.

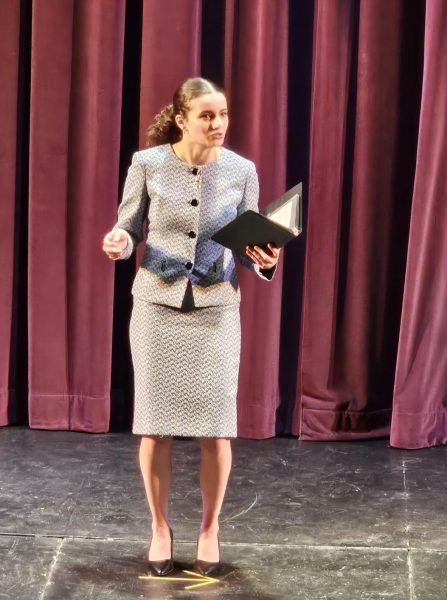

Colleen Dredell, director of research at the San Francisco-based nonprofit Next 10, emphasized that the goal of the collaborative report, entitled “The Future of California’s Water-Energy-Climate Nexus,” was to come up with solutions that would help California meet its targeted energy and greenhouse gas goals by 2030. Currently, California is not on track to meet these goals.

Dredell stated that in addition to California’s droughts, “supply and population growth trends are leading to further constraints and further challenges in terms of carbon intensity in the water sector,” which is keeping California from meeting its emissions targets.

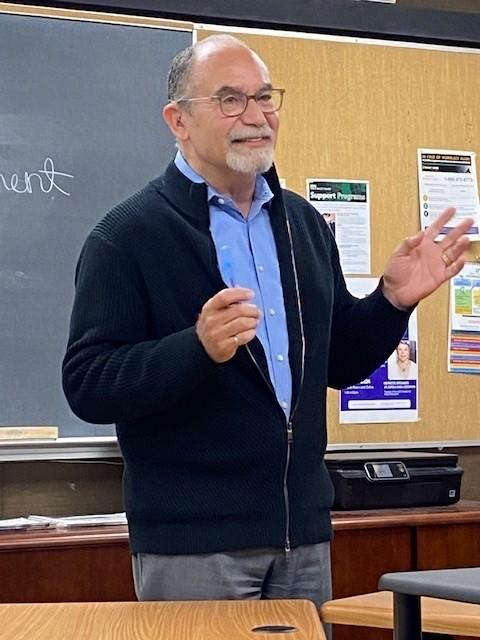

According to Dr. Peter Gleick, president emeritus at Pacific Institute, headquartered in Oakland, “California’s water system, the entire system – from collection, to distribution, to use, to treatment of water – is responsible for a very significant fraction of California’s energy use.”

Gleick said that 20 percent of California’s electricity, one-third of its non-power plant natural gas consumption, and 88 billion gallons of diesel consumption annually go to the state’s water system – which makes the way we use water a critical piece of our climate response.

The State Water Project, a water delivery system that provides water to much of California, is the single largest consumer of electricity in the state, he added.

Dr. Julia Szinai, a researcher at Pacific Institute, explained the methodology behind the study. One of the steps the research team took was to look at the water cycle and sources of water, Szinai said, because “energy is required to power all stages of the managed water cycle.” The researchers also found that “local surface water is the least energy intensive, whereas desalinated water (seawater) is the most energy intensive,” according to Szinai.

The team also chose to look at different scenarios for agricultural and urban sectors, breaking their analyses into five-year increments between 2015 and 2035. The urban study, conducted from statewide data, took information from the 2015 Urban Water Management Plans. In it, three situations were presented: a high scenario assumed that water use per capita would rise along with population, a mid scenario assumed that water use per capita would be constant but the population would still grow, and a low scenario assumed that water use per capita would decrease by 2 percent per year.

After collecting data, the research team found that residential water use is more energy intensive than agricultural use – meaning that improved efficiency in this sector could lead to the greatest reductions in carbon emissions. Szinai said that even in the mid-level scenario, California could still expect water demand to rise by 24 percent, making water conservation crucial to achieving lower urban water usage.

Agricultural results were surveyed using a similar method, and included climate and urban growth assumptions, she said. In the high scenario, researchers assumed that urban growth would decline, producing the least environmental impact; in the medium scenario, medium urban growth was assumed; and for the low scenario, they envisioned high urban growth with increased encroachment on agricultural land resulting in the most harmful climate impacts.

The results for agricultural water usage showed that “urban growth will take agricultural land out of production and therefore lower our water use,” said Szinai. In addition, greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector could be decreased by about 60 percent through decarbonization of the electric grid and decreased water demand.

Heather Cooley, director of research at Pacific Institute, closed the webinar by offering some recommendations on how to make changes in water conservation. Some of these strategies include expanding urban water conservation and efficiency efforts, restoring groundwater levels, expanding more flexible and high-efficiency groundwater pumps, and improving water data and reporting.

Formalizing the cooperation between water and energy regulatory agencies and utilities is also important, according to Cooley, because it “can lead to reduced costs to consumers and certainly it can lead to faster decarbonization of California’s water systems and its greenhouse gas intensity.”