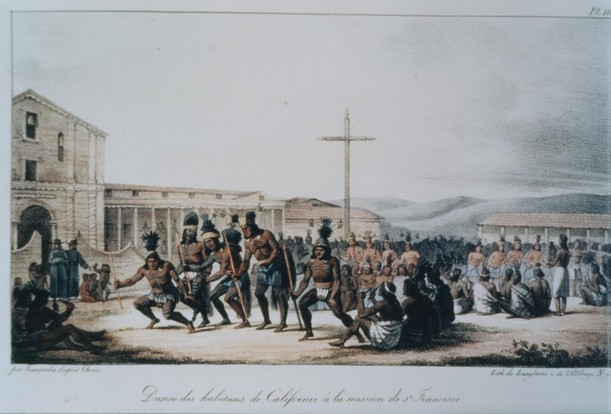

After a five-year effort, Diablo Valley College has successfully repatriated several Indigenous remains, funeral artifacts and cultural items to the Wilton Rancheria and the Muwekma Ohlone tribes. A private reburial ceremony took place Oct. 6.

The remains were returned in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, which says that all Native American remains and cultural items must be returned to their respective tribes by any institution that receives federal funds.

DVC is one of many colleges nationwide to have returned Indigenous remains to their respective tribes in the past year, but many institutions still hold hundreds if not thousands of remains. For example, UC Berkeley still holds over 11,000 remains, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

In response to the chronic delays by California colleges to return the remains and artifacts, Governor Gavin Newsom recently signed a bill that will require all schools within the CSU system to return Indigenous remains to their respective tribes as quickly as possible.

To date, more than half of the CSU campuses have yet to do so.

At DVC, the possession of remains and the process to repatriate them was first made public on Nov. 16, 2020, in a faculty email sent by President Susan Lamb.

The remains and artifacts at issue had been stored in an on-campus museum from the 1950s through the 1970s. After the museum’s closure in the 70’s, many of the artifacts were moved and stored in the campus library.

The human remains, however, were kept in an undisclosed building that only the college’s presidents had a key to. Lamb told The Inquirer that she was made aware of the remains’ existence when she became the school’s vice president of academic affairs in 2006.

The lengthy repatriation process proved frustrating, said Lamb, who blamed the federal government for adding layers of legal red tape to what she said should have been a simple undertaking.

“I think the U.S. government hasn’t necessarily made it easy,” Lamb said. “They have a whole process of either you’re a federally recognized tribe or you’re not, and that’s created issues for the tribes.”

The Muwekma Ohlone and Wilton Rancheria tribes did not respond to requests for an interview.

To begin the process of repatriation under NAGPRA, institutions must first notify the National Park Service detailing their inventories of human remains and cultural artifacts. California institutions must also notify the California Native American Heritage Commission.

Institutions must give notice to the National Park Service before the transfer process takes place.

At DVC, another cause for delay of the repatriation was the federal government’s failure to recognize the Muwekma Ohlone tribe, said Lamb.

NAGPRA is designed specifically for federally recognized tribes. Tribes that are not recognized must appeal to the NAGPRA Review Committee in order to take possession of the remains of their ancestors.

According to previous reporting by The Inquirer, much of the process at DVC involved identifying the remains and items, which required the assistance of anthropologists and other local Bay Area tribes.

The completed repatriation has now prompted the college to create a Native American Advisory Committee to help navigate Native American issues going forward.

“[The committee will] have students, faculty, classified and management. We have all our constituencies involved,” said Lamb, and “we’ve already had people volunteering to participate.”

In an email sent to faculty on Oct. 12, Lamb announced that DVC would be placing a plaque next year in the commons to commemorate the school’s place in Native American history. The area can have varied purpose, she said.

“I think it also provides a place where we can work with the tribes and have gatherings, and have a celebration [with] education and hopefully commemoration going forward,” added Lamb.

“You know there’s a saying that if you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it.”