Stalking the idea of a relationship

April 4, 2016

There are two types of people in this world, those who genuinely enjoy romantic comedies, and those who use them as some strange guideline to set our own relationships against. I used to be the latter.

Cut to five years ago. Having just gone through a rough break up, I was living in my sweatpants, ice cream was my dinner, and big salty tears were my dessert.

For some reason I thought the best idea would be to watch romantic comedy after romantic comedy, wondering why the characters always ended up together in the end — no matter what craziness they put each other through — but I couldn’t. What was I doing wrong in my life that they were doing right in theirs?

It seems silly — but the thought that their life was fiction, and mine was not, never once crossed my mind. The only rational conclusion was that all these gorgeous women could act as insane as they wanted and their man would still come running back every time.

Maybe I wasn’t pretty enough? Or maybe I wasn’t clingy enough so he didn’t know I liked him? Or maybe I was too clingy and suffocated him? Maybe I needed to be more dramatic and crazy, since that seemed to work for the movie characters.

But wait, wasn’t it our shared craziness and drama that caused the relationship to end in the first place?

When the media has so much power that it can alter your views of what a “normal relationship” looks like, how long will it take you to realize the problem starts with yourself?

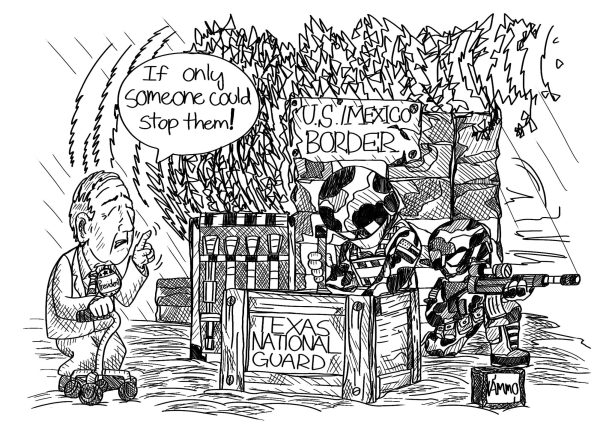

Whether we are conscious of it or not, women are being taught through romantic comedies that negative attention seeking behavior, altering their image to please a man, or stalking are all traits to tolerate in a real life relationship.

A study conducted by Julia Lippman in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Michigan on media portrayals of persistent pursuit on beliefs about stalking, has found that “media portrayals of gendered aggression can have prosocial effects, and that the romanticized pursuit behaviors commonly featured in the media as a part of normative courtship can lead to an increase in stalking-supportive beliefs.”

And these examples are paramount in the romantic comedy genre.

In case you haven’t been paying attention recently, here’s a few red flags: Meg Ryan decides to fly from Baltimore to Seattle because she thinks Tom Hanks, whom she has never met, could be “the one” after hearing his voice for 30 seconds on the radio in “Sleepless in Seattle.” Ben Stiller hires a private investigator to help him track down a girl thirteen years after their botched prom date in “There’s Something About Mary.” Hell, even Romeo and Juliet fall madly in love after knowing each other a whole 5 minutes, which is great, if you like stories ending in physician assisted group suicide.

I can’t tell you how many times in the past few years I have heard the phrase, “oh, we used to be friends, and then I found them again on facebook, and we’ve been dating ever since,” or something along those lines. This phrase is so ubiquitous in dating culture today that we don’t even realize that it too is stalking.

But isn’t Lippman saying exactly that? That we as the audience have romanticized the point so much that we don’t even see the problems blasting us in the face? When both movie and internet culture promotes the idea of stalking and negative attention seeking behavior in order to get what you want, it’s no wonder that we come out looking crazy.