Breaking Down the Rise of Student Debt

Hurdles in the Race to ’16: Issue #1

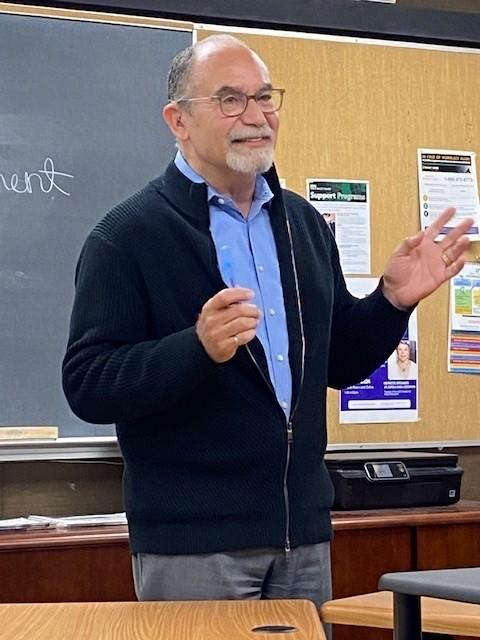

DVC Financial Aid reaches out to help students fund their futures at Pleasant Hill campus on September 10.

October 1, 2015

Here’s the deal: students owe a lot of money! In fact, it’s estimated that they have racked up a tab to the tune $1.2 trillion in loans. That number has quadrupled in the past 12 years. And apparently, with a nearly doubled default and delinquency rate, we’re not quite paying the bills.

Somewhere between the soaring cost of college and the subsequent increased borrowing has left students drowning in debt that could easily compete with their parents’ mortgage. That impending doom can prove to be a real distraction when you’re trying to focus on that statistics midterm.

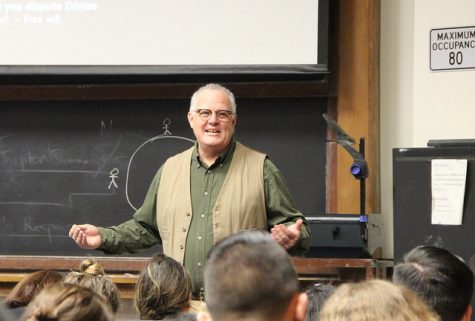

But before we can fix what’s broken, we must first identify the factors that have contributed to the breakdown. That’s exactly what Adam Looney, Treasury Department and Constantine Yannelis, Stanford University Department of Economics, attempted to do in a recent analysis. Looney and Yannelis compared Federal student borrowers’ debt to earnings claimed on tax records and found that there have been major shifts in borrowing trends.

As it turns out, for-profit colleges have been the primary culprit in the rise in student debt. Community colleges also bear some of the blame, to a lesser but notable degree. In the past, these types of institutions had a minimal share of the overall borrowing, but by 2011, they represented nearly half of the total debt and 70 percent of defaults.

Enrollment in both for-profits and community colleges increased when the recession hit and left adults unemployed and college-age students with less than ideal finances. As reported by The Chronicle of Higher Education, college enrollment increased nearly 7 percent between 2006 and 2010.

Amidst those circumstances, many people flocked to slightly cheaper educational institutions with more lenient admission standards to beef up their skill sets, and many took out loans along the way. Unfortunately, both for-profit and community colleges have sorely low completion rates and an abundance of students find themselves trying to pay on loans for education that somehow fell short. Even those that do graduate from “non-traditional” schools find their wage-earning potential to be less than adequate.

But it’s not entirely fair to scapegoat “non-traditional” student borrowers for the whole crisis when comparing the mounting cost of traditional schooling. Public school undergrad tuition, room and board rose 39 percent between 2002 and 2013, according to the National Center for Business Statistics.

Although for-profit and community college student debtors are responsible for the majority of defaulted loans, “traditional” four-year graduates are far from delinquency exemption, as 27-year old Megan Riley reiterates. When she attended Cal State Hayward, she only knew that she needed a degree, any degree, to be successful in the harsh job market she was about to enter.

After graduating, she realized her marketing degree wasn’t enough to compete against those with real experience. Making matters worse, she later realized she actually hated marketing in general. Riley took a job that barely paid the bills and certainly doesn’t make a dent in her student loans.

“I don’t regret my education, but if I had to do it all over again, I would’ve made very different choices,” said Riley. “If I knew I’d be paying forever, I would’ve chosen what makes me happy instead of what made sense.”

The debt crisis is forcing people outside lecture halls to start taking notes, and presidential hopefuls to offer up solutions. Now it’s time to listen up and choose the candidate with the answer that makes sense to you.