Scrambling for Eggs: How Consumers Are Coping with Scarcity and the New High Cost Per Carton

While shopping in the dairy section of her local Costco in Concord recently, Lauren Hugh snapped a picture of a sign announcing a two-egg limit per customer.

“I never thought I’d see the day when eggs are a rarity,” said Hugh, 46.

Yet strangely, that’s what they’ve become. In a matter of months, an inexpensive staple in nearly every family’s refrigerator—a carton of eggs—has turned into a semi-luxury item. According to The Guardian, egg prices in the U.S. jumped by 60 percent in the final months of 2022 and have continued to climb in the new year.

This increase, which began in November 2022, means consumers are now spending more than $4.25 for a dozen Grade A eggs on average. That’s nearly two and a half times what a carton of eggs went for a year ago when it cost around $1.72.

The average person goes through about a dozen eggs a week, making them one of the most purchased items at grocery stores, according to 2023 data from Business.com.

Akani James, a 20-year-old student at CSU Monterey, said it has been a while since he and his housemates have been able to find eggs in bulk at Costco. “With four broke college students living together, eggs were something we could always count on, but now we can’t find them,” he said.

Economists say a combination of factors is to blame for the steep price hike—from general inflation hitting foods of all kinds to a rise in disease among chicken populations, particularly avian bird flu. According to the Centers for Disease Control, “the Avian Flu has wiped out over 57 million chickens across the U.S.”

As a result, for months, farmers across the country have been killing flocks to prevent the disease from spreading, which has led to fewer hens laying eggs. Now, in addition to the higher costs per carton, egg aisles in many stores have gone bare, leaving people scrambling to find eggs as stores impose a limit of one carton per customer.

“We get huge pallets of eggs every morning, and it still doesn’t last all day,” said Megan Turner, a manager at the Costco where Hugh was shopping. Turner says that because of the shortage, “every Costco in the Bay Area has implemented the limit on eggs.”

Davonne Johnson, co-owner and operator of Johnson Farm, located in Briones regional park in Martinez, said her animals had not been affected by bird flu. Still, the impacts of inflation were distressing.

“Inflation has caused the costs of feed, operation, and labor to rise,” said Johnson. As a result, “many farmers have had to up their prices against their will,” she added.

Every month, Johnson and her husband fill their truck with diesel gas and drive north to Petaluma to get their animal feed. With soaring gas prices and the cost of feed doubling last year, she said they had no choice but to raise their egg prices in order to support themselves.

“We don’t want to outprice our customers, so we were careful about that, but in the end, we have to make a little bit of money,” Johnson said. Ultimately it’s up to grocery stores to determine retail pricing, she added, and they often “mark up prices by a couple of dollars,” passing the costs on to consumers.

Leslie Citroen, a chicken farmer from Mill Valley Chickens, explained that eggs used to cost so little because they were mass-produced. “The reason eggs had been so cheap is that they come from factory farms where animals are much more susceptible to disease and cruelty, hence the Avian flu,” Citroen said.

She encourages people to purchase pasture-raised eggs from small farms that treat their animals more humanely. However, amid the economic chaos driven by today’s egg shortage and inflation generally, she said she understood why it’s hard for many people to make an ethical, healthy purchase without overspending.

Lately, many people have turned to alternatives such as buying directly from farms like Johnson’s and Citroen’s, while others have gone straight to the source—purchasing the chickens themselves in order to eat their own eggs at home.

Others have resorted to making social media jokes about becoming egg dealers and creating an illegal underground black egg market. No matter how people are coping, the high demand for eggs is something they have to live with.

Lucy Diaz, a 58-year-old mother of four, said she tries to stick to buying organic eggs, but like many others, she’s had to switch to buying conventional eggs to save cash.

“Eggs are my go-to for meals,” Diaz said. “I have many mouths to feed and do not get paid enough to spend double digits on eggs.”

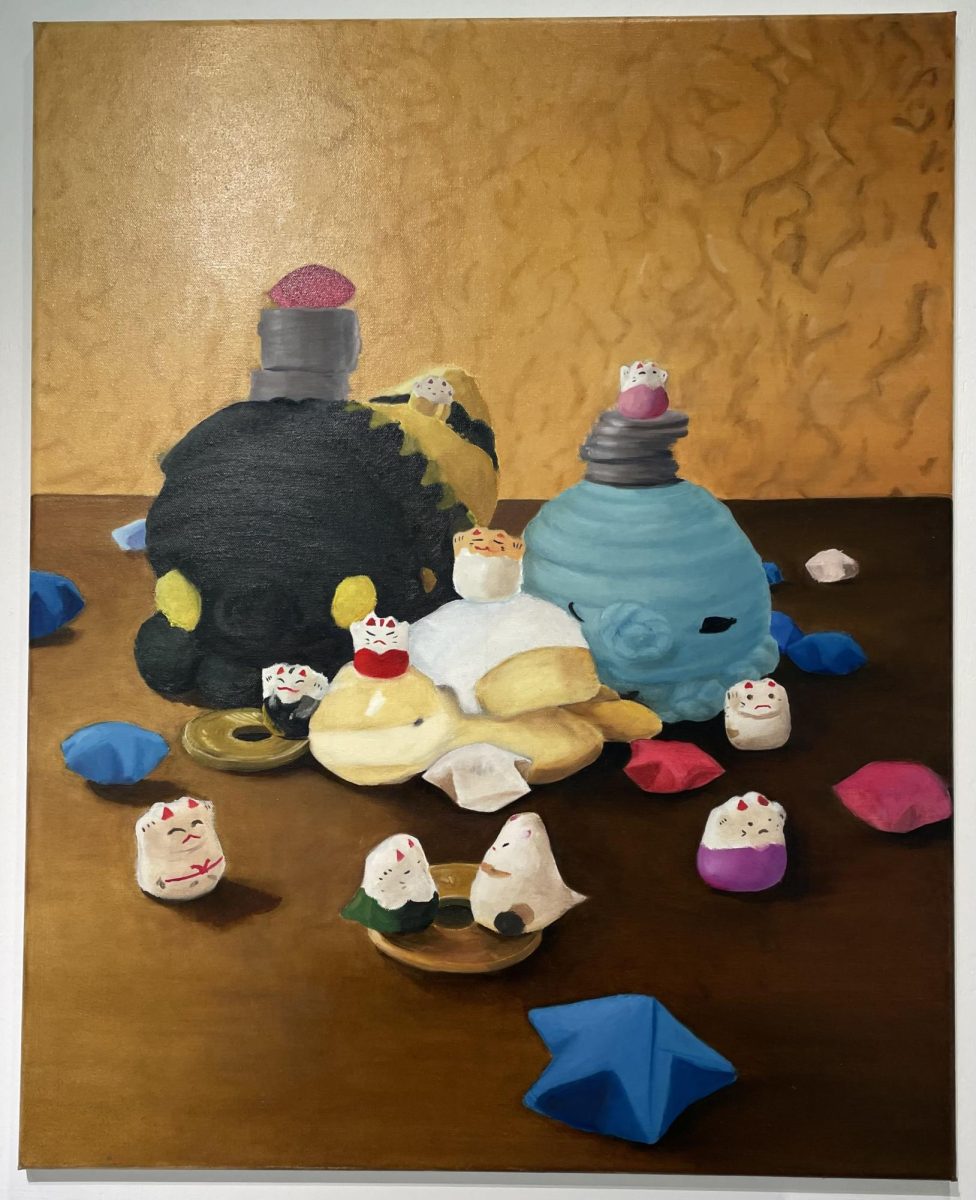

(Illustration by Ericka Carranza)

Todd Farr • Feb 16, 2023 at 8:11 am

The DVC Food Pantry located in the Student Union Building has eggs twice a month for distribution of a 1/2 dozen for those in need. The pantry is open Wednesdays and Thursdays 10:30-4:30 pm.