60 years of Inquirer history, Part 4: 1990s are a time of newsroom turmoil

Scott Hawkins, a victim in the recent campus killing at Sacremento State University, being taken awayby paramedics. This photo, picked up by the Associated Press, was taken by former Inquirer phot chief Adalto Nascimento, now online editor at “The State Hornet.”

December 8, 2009

Students rushing to early morning classes Oct. 24, 2006, were greeted by road blocks and police officers.

Bomb threats would shut DVC down for the next two days. In fact, two separate threats had rattled college officials the previous day, but classes went on as usual before the Walnut Creek Police Department’s bomb squad and the FBI were brought in to investigate.

Ann Stenmark, The Inquirer’s instructional lab coordinator, had arrived before 7 that morning for her other campus job. She quickly called faculty adviser Jean Dickinson before grabbing her own camera to take pictures that would run in the paper three days later.

Roused from their beds, two editors headed for campus and a hastily called a press conference in the overflow parking lot. Later, the staff gathered at Peet’s Coffee & Tea in Walnut Creek. With no access to their computers and page software, stories would have to be rewritten or started from scratch.

The big question, Stenmark recalls, was how to design and lay out the newspaper. The students got permission to work at the Contra Costa Times, where they were allowed to use a single computer until 9 p.m. when the Times’ staff needed it back.

“I was so proud of them,” Dickinson recalls. “While other students were enjoying a two-day break, The Inquirer staff was working like real professionals.”

A former “Contra Costa Times” reporter, Dickinson was hired in 1994. She still remembers her first meeting in The Inquirer’s cramped classroom with editor in chief Tony Hicks and staff writer Karl Fischer.

Hicks and Fischer set off for Safeway, saying they were hungry. Returning to the classroom, Fischer opened an unused black garbage bag and carefully lined a wastebasket. Hicks then dumped in a half-gallon of mint chip ice cream, followed by a big bottle of Sprite.

After witnessing the two slurp up the milkshake, Dickinson recalls thinking, “My god what have I got myself into, these people are crazy.”

Dickinson remembers Hicks as “absolutely passionate about his work .” And Fischer was “unstoppable.”

“There was a lot of pressure, but there was also a lot of joking around,” says Hicks, who is now the humor columnist for the “Contra Costa Times.” Fischer is the cop reporter at the “West County Times.”

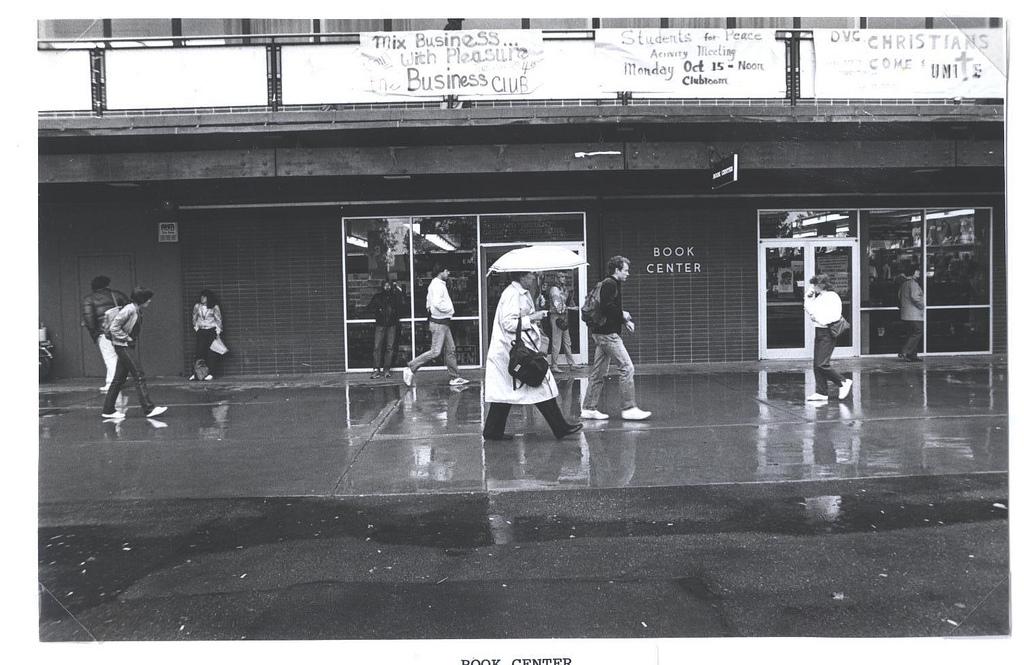

During those years, the staff used computers to put the paper together, but their page designs still had to be printed out on legal-sized paper, cut up, pasted back together on oversized boards, and then driven to the “Contra Costa Times,” where The Inquirer was printed.

It would be much later that Dickinson and Stenmark brought the newsroom up to industry standards by investing in new computers and software that allow students to send the pages digitally to the printer.

The Inquirer has covered everything from underage drinking by student leaders to the faculty’s 92 percent vote of no confidence in then DVC President Mark Edelstein, and more recently, the cash-for-grades scandal.

But Curtis Pashelka says it’s not the stories or the awards he remembers, but the friendships and the pranks .

Now a “Contra Costa Times” sports writer, Pashelka still recalls waking up one morning at a state journalism conference to find his car covered shaving cream and toilet paper.

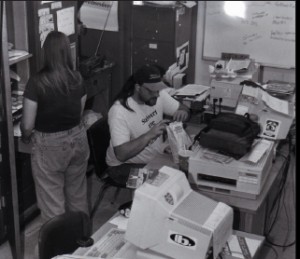

Former sports editor Aaron Williams works in the cramped quarters of the old Inquirer lab in 1995.

Kim Santos, who joined in 1997, remembers being excited by “uncovering a juicy story.” “It exposed me to real-life situations encountered in the industry every day,” says Santos, now editor in chief of the Hayward “Daily Review.”

In September, 1997, The Inquirer ran an editorial chastising the college for naming the new Student Union building after the late Margret Lesher in exchange for a $500,000 donation from her foundation.

“It is hard to be proud of an institution that is selling us out to a rich individual or big business,” The Inquirer wrote.

Fearful the editorial would jeopardize future gifts, President Edelstein called Dickinson and asked her to “educate” the editors so they would recant their editorial in the next issue. She refused.

“It was the beginning of the end of our relationship with the president,” Dickinson says.

Edelstein was particularly displeased after The Inquirer broke the story in October 1999 that DVC had canceled a Latin class it had started at two San Ramon high schools, because the course “did not exist.”

It had been deleted from the college catalog in 1988 and could not be revived without going again through the approval process. Meanwhile, the teacher could not be paid.

The Inquirer’s six-column headline and story did not go over well with Edelstein, who was hosting area high school principals at a breakfast meeting. That morning, The Inquirer was not included in the principals’ presentation packet.

When the paper covered the Latin story, Dickinson says, Edelstein occasionally hung up on reporters mid-interview and once told an editor, “I have no respect for your work.”

“Unfortunately, he had this idea The Inquirer should do P.R. for the college, rather than cover the news,” Dickinson says.

And journalism was the focus, even though not all Inquirer staffers went on to become journalists.

Ebony Sinnamon-Johnson joined in 1999 and says The Inquirer allowed her “natural curiosity to be manifested as a useful life skill.” She is now a special education teacher and is working on a master’s degree in counseling.

Iris Roe, who joined The Inquirer in 1999, says she learned how to ask the right questions and “make reluctant people talk,” a skill that has served her well as a public defender in Southern California.

Asma Nemati brought a fresh perspective in 2005 as an Afghan- Muslim-American woman. She credits the Inquirer for her love for journalism and now works in Kabul for “Free Speech Radio News” and blogs for the “Huffington Post.”

Adalto Nascimento, former photo chief and the first online editor, says his most controversial story was the cash-forgrades scandal.

“I can’t count how many times I drove down to the Martinez court house, trying to snap photos of suspects, their family, lawyers, or anything we could get,” recalls Nascimento, now the online managing editor for “The State Hornet” at Sacramento State University.