DVC removed our adviser: editor-in-chief speaks out

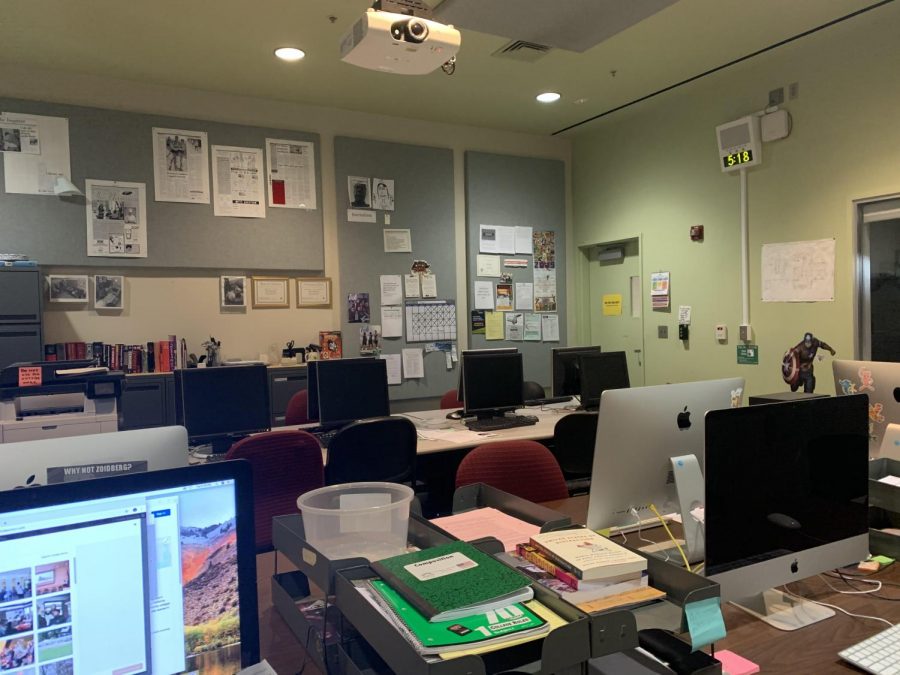

The Inquirer newsroom runs on Mondays to Thursdays and is student run, even in the face of our former adviser’s abrupt removal. (Emma Hall/The Inquirer)

October 22, 2019

It isn’t everyday that Diablo Valley College is featured on the front page of Inside Higher Ed, a publication out of Washington D.C., but the story they broke on Tuesday, Oct. 22 happened in my very own newsroom.

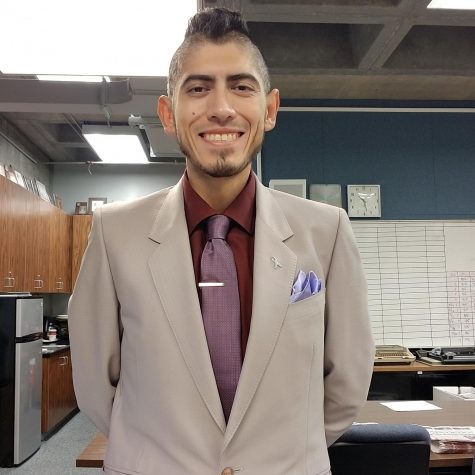

Fernando Gallo, our former adviser at The Inquirer, taught me a lesson I will never forget: fight for what you believe in. At a time when journalism is frequently under attack, this lesson has already served me well. But this semester, with Fernando’s sudden and unexplained removal, the past nine weeks have been a struggle.

Two weeks before the semester began, in August, I received news from Fernando that he would no longer be teaching his classes and was leaving The Inquirer altogether. He told me this immediately after he learned the news himself. It was on a Saturday, at noon, when Dean of Social Sciences and English, Obed Vazquez, through an email that simply said:

“Hi,

With the new schedule there are no classes for you.”

I was livid. How was I supposed to lead my newsroom without an adviser? What was the future of The Inquirer? What was going to happen to Fernando? But most importantly, was he removed because of our reporting?

Several times in the spring, The Inquirer received backlash from our coverage on the racist graffiti. DVC President Susan Lamb claimed an editorial we wrote was spreading “misinformation” when we summarized our reporting. Lamb’s message was sent through an email addressed to every faculty member on campus. She also stated, “I do not know if the Inquirer will publish the corrected information, but I thought that the college community should be informed.”

As editor-in-chief, I can say with full confidence that our racist graffiti coverage was always factual, accurate, and informative. After Lamb sent that email, Fernando met with her, Vice President of Instruction Mary Gutierrez, and Dean of Social Sciences and English Obed Vazquez to express concern and defend our reporting. I was not there during this meeting, but from what I was made aware of, the situation seemed to get resolved.

The Inquirer also received a handful of negative Letters to The Editors after we published that Dean of Student Services, Emily Stone, was on her phone during a listening circle event. The situation escalated when the head of the history department, Matthew Powell, according to Inside Higher Ed, came to our newsroom and attempted to intimidate Fernando into publishing his own letter defending Stone.

For the sake of transparency, I published the first two letters we received. But after we continued to receive more letters from faculty, the editorial team made the decision that The Inquirer would not publish any more, as they added nothing new to the previous letters. During all of this, Stone did not reach out to The Inquirer once. This was a lot to take in as an editor-in-chief of a community college newspaper. But throughout all this conflict, Fernando had our backs. He taught us to stand up for our reporting and our First Amendment rights.

To provide some background, Fernando means a lot to me as a student journalist. Because of my position as editor-in-chief, I worked with Fernando closely and frequently. He will always be my mentor, a person who I will remember as I move on to study and practice journalism in the future.

In today’s political climate, it is no secret that being a journalist is increasingly difficult. There has been a visible change in the profession since Donald Trump has taken office. I have found it difficult to be a journalist without being deemed “the enemy of the people.” Last year, the United States was added for the first time to the list of most dangerous countries to practice journalism. In that year, 63 journalists were killed while on the job globally according to Reporters Without Borders. Last year, in Annapolis, Maryland, the Capital Gazette’s newsroom experienced a mass shooting that killed five members of their staff. This is now a profession that increasingly costs journalists their lives.

Fernando is also a Mexican American journalist at a time of terrorist attacks against members of the Latinx community, such as the horrors in El Paso and Gilroy, the need for Latinx journalists is vital. We need those voices and perspectives in a time where they are often being disregarded.

Challenges often arise as a student journalist when people don’t take us seriously simply because we are students. Being a young woman, I encounter even more obstacles. I have been underestimated and disrespected because of my gender while reporting and doing my job. Misogyny is inescapable in this male-dominant field. But this type of behavior was never accepted in a classroom that Fernando facilitated.

Fernando is the type of instructor who empowers and stands up for his female students. He not only stands up for women, but he is overall an ally for the underdog. In fact, when we discovered the first incident of racist graffiti, he encouraged us to tackle the story head-on, as it seemed the feelings of students of color were being ignored. When he sees someone being harmed, Fernando stands up and fights for them. That behavior taught me courage.

I was thrown into the editor-in-chief position in Spring 2019 as a second semester freshman. There were more than just butterflies in my stomach, more like extreme anxiety. When you are editor-in-chief you make the final call. You are running a newsroom for three hours a day from Monday to Thursday. (Currently, I have clocked 80 hours working in The Inquirer newsroom this semester so far.) My job is to make sure deadlines are met and stories are published, all while keeping newsroom morale up and maintaining the public appearance of the publication.

With this responsibility comes overwhelming pressure, doubt, and insecurity. Yet, having a right-hand man like Fernando made my job a lot easier. He provided reassurance of my leadership skills and taught me how to be a level-headed, yet bold leader. Often, I came to him with questions about journalism, leadership, and even about life. A thoughtful and insightful answer always came my way from him.

Fernando has an incredible wit, plethora of knowledge, and a kind heart that was always open to me and The Inquirer reporters. I will always remember the time where Fernando told me that, no matter the occasion, he would always stand by me. I had only known him personally for about two months. He was always there for not only me, but for The Inquirer and his other students.

He taught at DVC for four years and has taught every journalism course at the college: JRNAL-110, JRNAL-120, JRNAL-130, and The Inquirer classes: JRNAL-126, and JRNAL-127. Last spring, Fernando was also teaching at Los Medanos Community College and San Francisco State. Overall, he was teaching six classes. It would be an understatement to say that Fernando is dedicated to his craft. Teaching journalism is his calling. I was lucky to have an instructor like him, especially after what my newsroom went through last semester.

But then why was Fernando removed? There still is no clear explanation or answer. I sincerely hope DVC didn’t remove him because of our reporting. If so, that would be a violation of the California Education Code 48097, which states the following:

“An employee shall not be dismissed, suspended, disciplined, reassigned, transferred, or otherwise retaliated against solely for acting to protect a pupil engaged in the conduct authorized under this section, or refusing to infringe upon conduct that is protected by this section, the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, or Section 2 of Article I of the California Constitution.”

Like any good journalist, I am asking more questions about Fernando’s removal than have been answered. Was Fernando removed because of who he is as a person? Was it because he expressed his concerns about how the graffiti was handled as an instructor of color? Was it because he stands up for others regardless of whose toes he steps on? Is it because he defended his students? Or is it because he is an outspoken Mexican American man who is being racially profiled by the college for speaking out? Is diversity truly DVC’s strength when they got rid of an instructor of color in the program? Needless to say, I am still seeking my answers.

Fernando is a passionate, down-to-earth, and caring teacher—if anything he is the greatest instructor I’ve had. I am disappointed that future journalism students at DVC will never get to know him.

I find that my newsroom is no longer the same unified space it once was. Fernando was the one who truly made The Inquirer my second home. But with his absence, I find it difficult to keep the same motivation I had in the spring. I find it difficult to reassure my fellow editors and students that everything will be fine. Several times this semester, I have met other students of Fernando’s who have expressed disgust over his removal. I share the same sentiment, if not more so. I will never forgive DVC for removing Fernando.

As the editor-in-chief of The Inquirer, I am unsure of the future of the paper and the department. I met with Vazquez and English Department Chair Alan Haslam to discuss what exactly was going on after I learned of Fernando’s removal.

Currently, the journalism program is under a “revitalization” process because of low student enrollment. However, according to Mary Mazzocco, the former journalism chair, low enrollment was never a struggle for 110 and 120. In fact, there are so many students wanting to take 110, that the number of class sections has increased. The only courses that have suffered from low registration were The Inquirer classes and 130 (multimedia journalism). But low enrollment is a problem for all journalism programs across the state, according to the Journalism Association of Community Colleges.

There will be changes coming to the department, but those adjustments could mean gutting the program. If The Inquirer and the department don’t enroll more students, we could be looking at the end of journalism at DVC.

Overall, I am unsure of the future. This is my last semester with the program and the paper. Hopefully, DVC changes how they treat this department, its faculty, and its students.

Van Torma • Oct 30, 2019 at 7:17 am

I have a question for the Editor in Chief . You state that “Fighting for what one believes in is a quality that you find of paramount importance..

However, as a reader to this newspaper, how do I determine or glean what you are fighting for iif you just generalize and fail to provide any substantive details on this “ fight”

Warm Regards, and Confused

Marc McCormick • Oct 24, 2019 at 3:36 pm

“Fernando told me that, no matter the occasion, he would always stand by me.”

That’s actually not a good quality. When someone is wrong, they need someone to pull them aside privately & explain why they are wrong & offer a solution. But standing by someone even when they are wrong is just a “yes person” and “yes people” get others in trouble.