In late October, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Héctor Tobar visited Diablo Valley College to discuss his most recent book, Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino,” which came out in May 2023.

“This book that I wrote, Our Migrant Souls, is building on a very deep intellectual tradition, which is the tradition of writing about race in the United States,” Tobar told the audience of students assembled by the Puente Program, whose co-coordinator, English professor Anthony Gonzales, organized the talk.

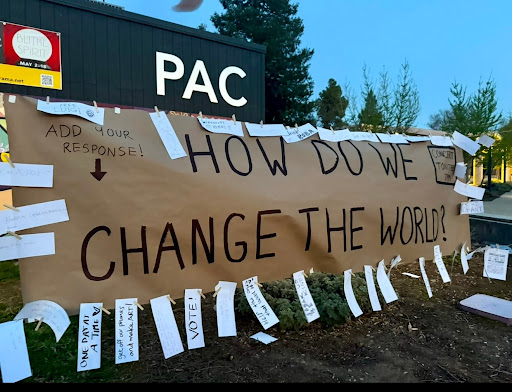

At the event, Puente students were invited to discuss their take-away from Tobar’s book.

Edwin Hernandez, a computer engineering major, expressed gratitude to Tobar for writing his book, which he said taught him a great deal about his own history and heritage. Hernnadez shared his own father’s personal journey from the Sonoran Desert of Mexico to the U.S. in the effort to better provide for his family.

“They have missed lots of life experiences in order to give me the life I have now,” Hernandez said, describing the sacrifices of not only his parents, but of many other immigrant parents who dropped out of school and worked endlessly to provide their children a life they had only dreamed of.

Not only do Latino immigrants work to provide their families better opportunities, but they also play an essential role Latinos play in America, Tobar said. “We all know that this country does not eat without Latino labor.”

The focus of Tobar’s talk, and book, revolved around a question of identity and a re-evaluation of the notion of race.

“What does it mean to be Latino?” Tobar asked. For much of American history, he said, the answer has been out of the hands of Latinos.

“People think that because of our origins, our biological origins, we have certain qualities,” Tobar said. “One of the first things I learned… in my fifties, is that race has no basis in science.”

Tobar, a second-generation Guatemalan immigrant, shared that his parents’ race is listed as Caucasian on his birth certificate because in the 1960s, the U.S. government had not standardized the use of the terms Hispanic or Latino. That doesn’t mean scientists studied or analyzed DNA, Tobar explained, but rather that being Latino means having a “racial relationship” with the United States.

“Latino is a story of an empire,” said Tobar. “Behind the idea of Latino identity there is the border.”

Tobar clarified that race is an idea, and racist ideas, which frame types of people in a certain way, justify inequality. “We’re just all different shades of brown, but white and black are real ideas in our society, because they’re from a way of thinking, of creating ideas of inequality,” he said.

Tobar referenced Donald Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally, the week before the presidential election, at which comedian speaker Tony Hincliffe mocked and made degrading assumptions about the people of Puerto Rico.

Tobar also addressed racism in the representation of Latino people in entertainment media, noting the unflattering association between Latino characters and cartels in TV shows.

Tobar said that some white American writers, angry about economic inequality, project their frustration with corporations onto drug cartels and scapegoat Latinos in the process.

Tobar added that the non-Hispanic screenwriters of such shows and movies typically choose “authentic” names for their characters. “There’s too many José’s. So Hector – because it sounds exotic,” Tobar added jokingly.

These reflections enabled Tobar to criticize the idea of race. “That’s how my book came to be,” he said. “It’s an assimilation of this attempt by many scholars to fight back against the prejudice and stereotypes that exist against us.”

Sharing a passage from his book, Tobar read, “Our collective origin story is a million unfilmed soap operas and a million unproduced ‘Hamlets.’”

“We are our history,” he added.

This article was updated to make the following corrections: Anthony Gonzales is the co-coordinator of the Puente Program, not the director.